In Russia, it seems, they have not learned to talk about the introduction of troops into Poland in 1939. For the majority, the War (with a capital letter) began on June 22, 1941 – this is how everyone was taught from childhood, and what happened before, they say, who knows. For the scientific minority, the world war began on September 1, 1939, with the attack of the Nazi troops on Poland, and any Soviet or post-Soviet intellectual will remember that German iron tanks were thrown at the Polish cavalry. A typical example is Brodsky's poems, which are called “September 1, 1939”:

The day was called "the first of September".

The kids went, because it was autumn, to school.

And the Germans opened the striped

barrier of the Poles. And with the buzz of tanks,

like a fingernail – chocolate foil,

smoothed out the lancer.

But the narrative of the discussion of their own Soviet invasion of Poland, which began 83 years ago, on September 17, 1939, did not work out. There are a number of reasons for this: in Soviet times, this topic was diligently hushed up, and in the nineties it was not really reflected on, whether on purpose or not – now it's hard to say.

Only an absolute minority of people in Russia – and more broadly in the Russian-speaking space – have discussed and are discussing that war, which in encyclopedias is called the "Polish campaign of the Red Army." At the same time, any attempts to critically comprehend what was happening are almost inevitably perceived as something hostile, "Russophobic", "renegade". Such is the force of inertia of the Soviet discourse about the war, which, let me remind you, in modern Russia cannot be violated under pain of criminal prosecution.

Only an absolute minority of people in Russia discuss the "Polish campaign of the Red Army"

At some point, now or later, when hands finally reach it, those events will still have to be discussed. But as is often the case, before constructing a new narrative, the old ones must be deconstructed. The easiest way to find them is in the world press of September 1939.

It is interesting, by the way, that in contrast to the German and Anglo-Saxon press, the Soviet media reported practically nothing to the day about the entry of troops into Poland. For example, the newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda, the mouthpiece of the USSR Defense Commissariat, on the day the campaign began, limited itself to bravura reports about the successful course of the draft campaign throughout the country.

This is not a random detail. In Soviet Russia, it was not the business of readers to decide what would be reported and when. This was to be decided by the top party leadership. In this silence, there is an extra reminder of the lack of rights of the “little man” in the USSR (I will note aside that many architectural critics say that the wide Stalinist avenues and skyscrapers also conveyed this very idea).

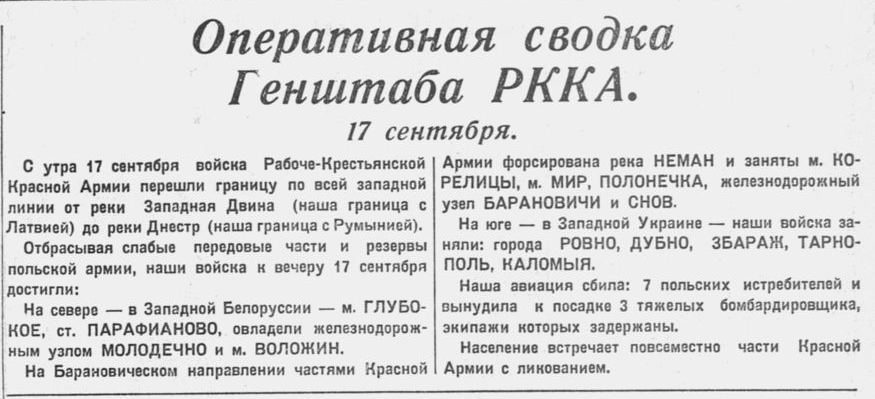

The first reports began to appear in the Soviet press only the next day, September 18, and the narrative began to be constructed along with them. Initially, as in the German press in the same days, the emphasis was on the fact that the Polish state turned out to be “unsound” and actually ceased to function, so the troops enter as if not for war, but to ensure “security”.

Troops enter as if not for war, but to ensure "security"

In general, it is characteristic in itself that the articles in the Völkischer Beobachter and in Pravda about Poland were almost copied. Here, for example, is a quote from the main NSDAP newspaper of September 17:

“… The Soviet government considers itself obliged, in order to protect its own interests and protect the Belarusian and Ukrainian minorities in Eastern Poland, to order its troops on Sunday, at 6 am Moscow time (4 am Central European time), to cross the Soviet-Polish border ".

Gradually, the Soviet narrative developed. Less and less was said about the collapse and insolvency of the Polish government, and the focus of attention shifted to the fact that “panish Poland” (a typical stamp of that time; and there was also “boyar Romania”) offended Ukrainians and Belarusians in every possible way, so it was necessary to help them .

"Pan Poland" offended Ukrainians and Belarusians in every possible way, so it was necessary to help them

It is curious that, from the point of view of formal logic, these two theses (1) Poland failed as a state; and 2) Poland was a strong state that exploited our brother Slavs) are not very linked with each other, but this, of course, did not bother anyone. It’s just that the second narrative gradually replaced the first one as the troops advanced, and the newspapers, of course, also did not forget to report about their meeting with “widespread jubilation”.

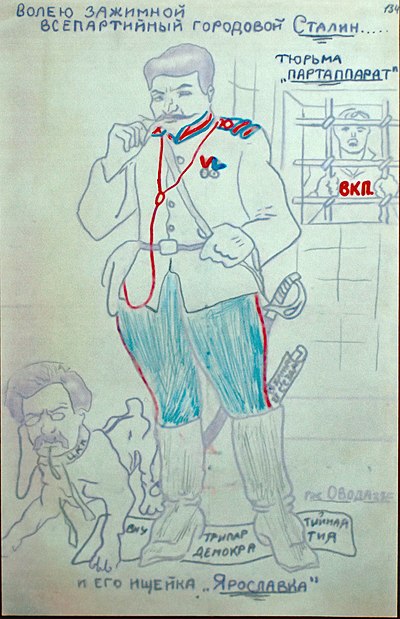

Take, for example, the programmatic article in Pravda on September 19, authored by Emelyan Yaroslavsky (it was his left opposition in the 1920s who was depicted in caricatures as Stalin's pet dog). Here are the main theses:

- we go to help our own;

- western Belarus and Ukraine were only a colony, an appendage of the "main" Poland;

- local residents are dissatisfied with the Polonization;

- there was a "desecration" of the national culture of these peoples, they were not allowed to fully learn in their languages and use them.

It was constantly emphasized that we are talking about "brothers" who need to lend a helping hand. And, of course, the author did not skimp on emotions. Here is a typical excerpt:

“Wherever our units appear, our brothers greet the valiant Red Army with exceptional enthusiasm. With tears of joy, they throw themselves into their arms, offer apples, milk. The joy is so great that every peasant is ready to give away the last mug of milk, to share the last piece of bread. In many places, even as soon as the Soviet troops approached, the population was tearing down Polish flags and signboards of government offices, hanging red banners on the streets.

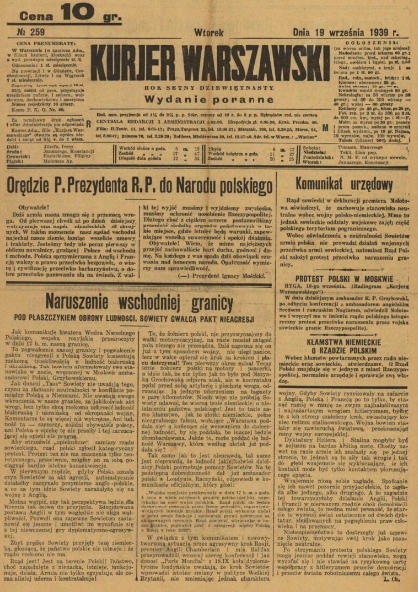

On the same day, September 19, the Polish newspaper Kurier Warszawski published an article "Violation of the Eastern Border" with a demonstrative subtitle "Under the guise of protecting the population, the Soviet Union violates the non-aggression pact."

It is interesting that, in contrast to later interpretations, right then the Polish journalists from the capital, which was approached by armies from two sides, were softer. I think this can be explained by the fact that the secret protocol to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was not known then.

The authors of this note seriously tried to fend off Soviet propaganda clichés. Like, no, our state still exists. And no, we did not ask for protection, and the Belarusians and Ukrainians did not ask either. In general, they are all "decent and reliable Polish citizens." The author also discusses what will happen if Warsaw recognizes the actions of the Soviet troops as aggression (in the sense that London and Paris will not then declare war on Moscow, as they declared before Berlin). However, the author here also did not know that there were also secret agreements between Britain and Poland: according to which security guarantees concerned only Germany.

Polish journalists wrote: “No, we didn’t ask for protection, and Belarusians and Ukrainians didn’t ask either.”

The British press itself in the overwhelming majority of cases described the offensive of the Red Army negatively and critically. At the same time, the discourse was also offered understandable to readers: for example, in The Times, the actions of Berlin and Moscow were called a new partition of Poland, and the Red Army was actually accused of invading. At the same time, we can say that this story was somewhat simplified: obviously, British journalists believed that their audience did not really understand Belarusians and Ukrainians. For example, one could read in the Daily Express about "unsubstantiated allegations [of Moscow] about the suppression of Russian minorities in Poland."

The Daily Express wrote about "Moscow's unsubstantiated claims about the suppression of Russian minorities in Poland"

At the same time, American newspapers behaved much more calmly, maintaining the general isolationist neutrality that was maintained at that time in the White House and the State Department. Most of the newspapers limited themselves to simply dry reporting of facts outlining Moscow's position.

History has put everything in its place. The conditionally British narrative (the fourth partition of Poland) has long prevailed in the world when talking about this episode of the world war. This is not accidental – it really is closest to the real facts (and not at all because there is some kind of conspiracy!). However, this is true in half of the world, but not in Russia. In Russia, the first three partitions of Poland were not strongly condemned, as was the entry of troops into Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Looking at the Soviet and British newspapers of September 1939, you understand that it is very difficult to take even a modern Russian layman and immediately plunge into this “British” narrative. Almost impossible. This will cause a very strong reaction of rejection, as the usual picture of the world will begin to crumble.