Just a year ago, in October 2021, world leaders gathered in Glasgow, Scotland to discuss climate change and a carbon-free energy transition. Now it's hard to believe, but it really was almost the most discussed topic of the past year. Covid had already become a routine, and there were still a few months before the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Almost all world leaders were at that summit, among others, the President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky spoke. He called Crimea and Donbas eco-time bombs. Only the leaders of Russia and China were absent from the summit. The British organizers even turned off the video link in the hall to prevent them from performing remotely.

Much was expected from that summit, but its results can be called satisfactory at best – there was no global consensus and no breakthrough. In 2022, environmental issues on the world agenda were sharply replaced by the war in Ukraine (although these issues themselves have not ceased to be either global or relevant), and energy issues have moved from long-term theoretical plans for many countries to a practical plane: how to heat in winter.

Against the background of the aggravated energy crisis, some European countries even urgently returned to coal and fuel oil. So what – all plans for the transition to green energy will now go to the trash? In short, no. On the contrary, everything will happen faster than expected: the stronger the energy crisis against the backdrop of the war, the stronger the desire of countries importing hydrocarbons to abandon them. Question: what has the world already done to switch to renewable energy sources?

What is renewable energy

Renewable energy sources (RES) are called so because they are replenished at a rate that exceeds the rate of consumption of this energy. This is their main difference from fossil sources (oil, gas and coal), the reserves of which, although huge, are still finite (according to modern estimates, oil and gas can end in about 50 years, coal in 70).

Oil and gas may run out in about 50 years, coal in 70

Another important feature of RES is environmental friendliness. This is especially important against the background of the fact that the main source of greenhouse gases today is the burning of fossil fuels. These gases (in particular, carbon dioxide) lead to the heating of the Earth, which can cause radical and irreversible climate changes.

In 2015, a special international conference adopted the Paris Climate Agreement, which aims to keep global average temperature rises “well below” 2°C this century and aim to limit growth to 1.5°C.

Five years later, in May 2021, the International Energy Agency (IEA), in response to the plans of individual countries to achieve carbon neutrality, published a road map, the joint adherence of which would allow the whole world to reduce emissions to zero by 2050 and achieve the requirements of the Paris temperature agreements.

This IEA roadmap implies work in a number of areas (political decisions, technologies, supply chains, etc. are needed), but stopping investments in fossil fuel projects and replacing the share of coal, oil and gas in the global energy mix with renewable energy is the foundation of this plan. .

The share of renewable energy is growing, while the price is falling

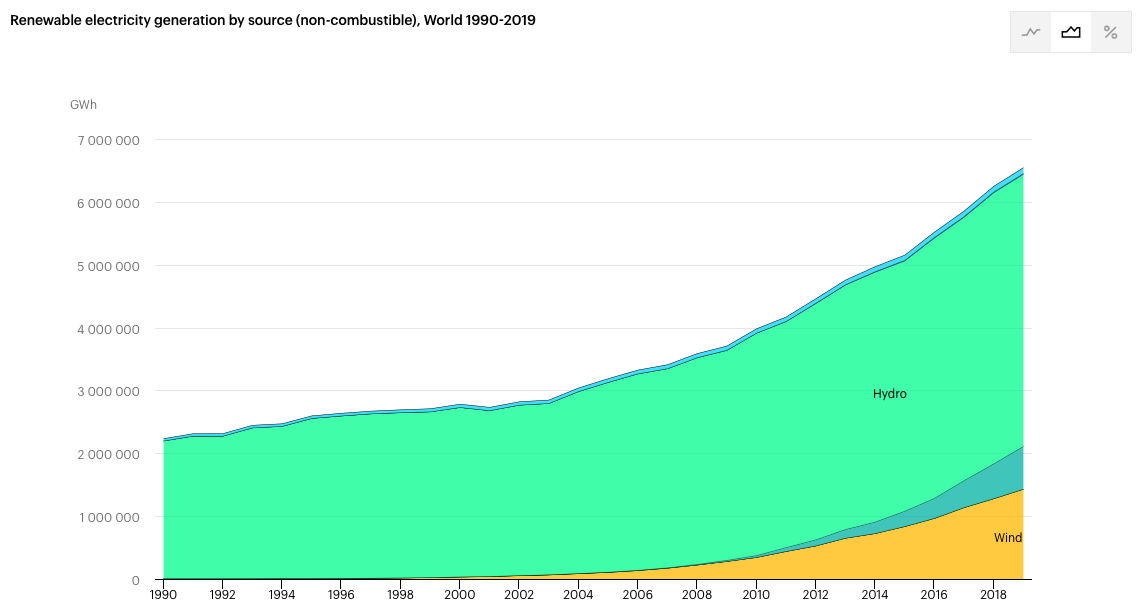

This is really happening. Regardless of the war and the current energy crisis, we can talk about a stable trend. The share of RES in the global energy balance is steadily growing : in 2020 it amounted to 5.7%, while in 2019 this figure was less than 5%. And the share of renewable energy in global electricity production is even higher: in 2020 it amounted to 29% (in 2019 – 27%).

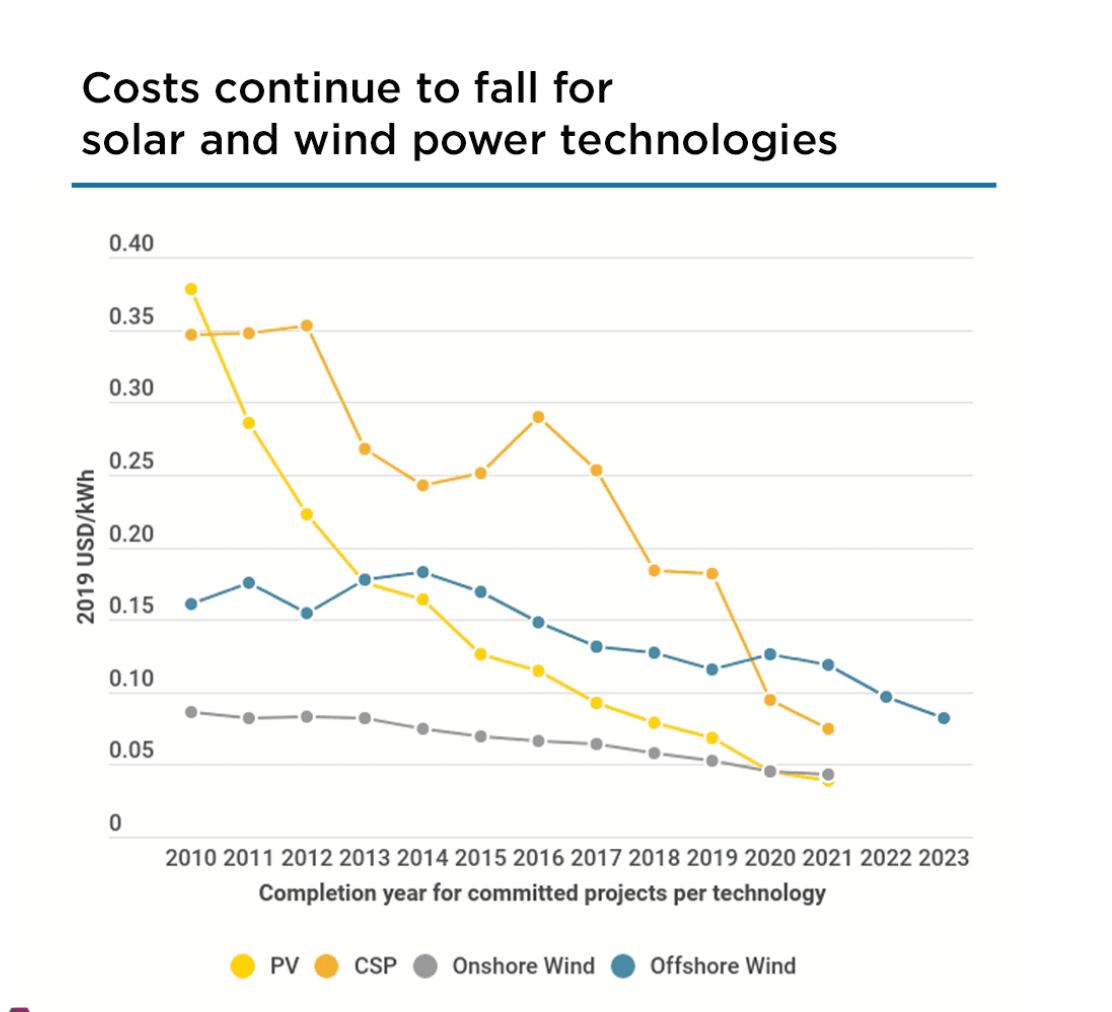

Over the longer term, wind and solar capacity more than doubled between 2015 and 2020, by about 800 GW, corresponding to an average annual growth of 18%. This is much faster than most market analysts expected. Why is this happening? First of all, because RES are becoming cheaper and more accessible. To give you an idea: the prices of onshore wind and solar energy have decreased by about 40% and 55%, respectively, over the past five years.

Onshore wind and solar prices have fallen by 40% and 55% respectively over the last 5 years

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency IRENA, from 2010 to 2020, the cost of electricity from solar photovoltaic systems for general use decreased by 85%, from concentrated solar energy (CSP) systems by 68%, from land-based wind turbines by 56%, from offshore — by 48%.

Prices for solar photovoltaic systems commissioned in 2021 fluctuate on average around $0.039 per kWh. This is 42% lower than in 2019 and 20% less than the cheapest fossil fuel competitor, coal-fired power plants. Simply put, it becomes simply profitable to refuse "dirty" coal.

The efficiency of investments in renewable energy has also grown: the same amount of money invested in renewable energy today produces more new capacity than ten years ago. In 2019, twice as much renewable energy capacity was commissioned as in 2010, and this required only 18% more investment.

RES as part of state policy

Until recently, the effectiveness of investments in renewable energy for business could not even be compared with the benefits of projects in the field of hydrocarbons. Nevertheless, this sector of the economy has received serious political support at the international and local levels, and without this assistance and subsidies, it would hardly be so developed today.

On the international stage, the European Union has been a global leader in the pace of the energy transition and the development of renewable energy sources for many years. In 2022, the EU countries adopted a new REPower energy plan, according to which already this year they will reduce the consumption of Russian gas by 67%, and “much earlier than before 2030” they will stop buying it altogether (important clarification: we are talking about a consistent rejection of any gas, not only Russian). However, given the way events are unfolding (in particular, given the recent "incident" at Nord Stream), perhaps everything will happen even more forcefully.

Already this year, the EU will reduce the consumption of Russian gas by 67%

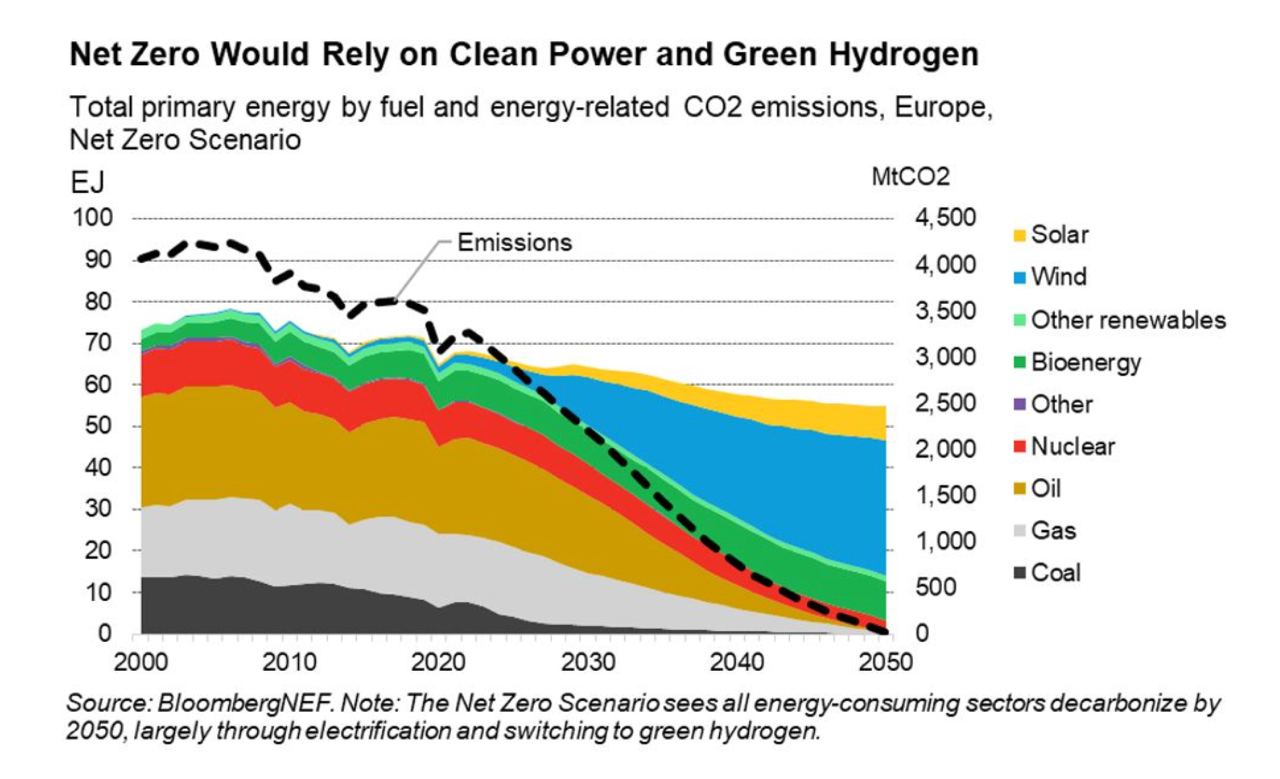

According to the European plan, in the first years, Russian gas will be replaced by similar supplies from other countries, as well as coal and fuel oil, but by 2030 the share of hydrocarbons and coal should be reduced due to the growth of the renewable energy market. A complete phase-out of fossil fuels in Europe is scheduled for 2050 and could cost $5.3 trillion.

In 2020, the share of renewable energy sources in the EU balance was 22%. By 2030, according to REPowerEU, this figure will rise to 45%.

In particular, the focus will be on the rapidly growing market for solar panels. By 2025, their number in Europe should double in relation to the current level – up to 320 GW, and by 2030 it will reach 600 GW.

A similar trend is visible in the US. 60% of all generating capacity to be commissioned in 2022 and 2023 will come from new solar projects.

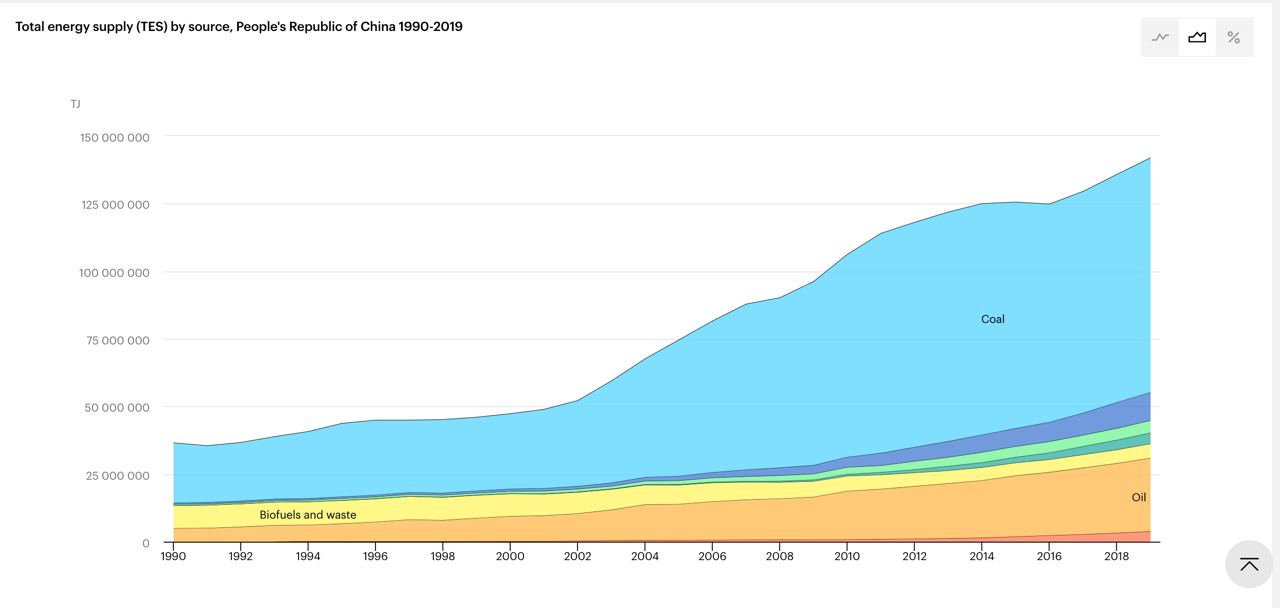

But the solar panel market has its own problem – localization. Over the past decade, the main production facilities have migrated from Europe, Japan and the United States to China, which has become a leader in investment and innovation in this segment. The share of China at all key stages of the production of solar panels today exceeds 80%, and in key elements (polysilicon and wafers), its share in world production will soon exceed 95%.

In general, the renewable energy market in China is growing steadily – and in terms of electricity production, it is more than twice the performance of the next US market. However, the volume of energy consumption and the rate of its growth in the country are so high that the share of RES is simply “drown” in the overall picture.

Wind energy

The wind energy market, although growing at a slower pace, today occupies the most significant share in the renewable energy “pie”. Last year, global wind power generation increased by a record 273 TWh, or 17%.

In 2021, China accounted for nearly 70% of wind generation growth, followed by the US at 14% and Brazil at 7%. In the EU, despite near-record capacity growth in 2020 and 2021, wind power generation itself fell by 3% last year due to unusually long periods of low wind (this factor also has to be taken into account).

However, even this is still not enough to meet the IEA's scenario of achieving global carbon neutrality by 2050, which implies a level of 7900 TWh in 2030. According to it, the average growth during 2022-2030 should be 18%.

Wind is one of the cheapest renewable energy sources. But even here there are “challenges”: fluctuations in the flow of energy depending on the season and time of day (the wind blows unevenly) and transportation (wind turbines are mainly installed in rural areas, on the coast or at sea, the question of energy delivery arises).

Building taller and larger “windmills” (the higher and larger the mechanism, the more wind it will capture), the development of intelligent modeling in machine learning to optimize the operation of turbines at different times of the year and day, as well as improving storage methods – these are the tasks that the solution of which will direct investments in the coming years. So far , there are only a few successful cases on the use of hybrid energy systems, but, most likely, the future belongs to a “smart” combination of several types of renewable energy sources, storage and reserve capacities.

Bioenergy

Bioenergy is already making an important contribution to energy security and the sustainability of the global energy system. Without her, the current situation would be much more difficult. As the world's largest renewable energy source, bioenergy promotes diversification, ensures energy security and pushes market prices to the limit.

Bioenergy is also the most versatile form of renewable energy. It can supply heat and electricity, be a fuel for transport or a source of biomethane (renewable gas). One of the key advantages of bioenergy is that it can use existing infrastructure, allowing for a rapid increase in the number of end uses of bioenergy. For example, biomethane can be used in existing gas pipelines and end-user equipment, and many liquid biofuels can be used in existing oil distribution networks and used in vehicles with little or no modifications. This is critical, for example, to reduce emissions from existing vehicle fleets in developing countries.

Today, the cost of biogas production in the world fluctuates in a wide range from $2/MBTU to $20/MBTU. There are also significant differences between regions; in Europe the average cost is about $16/MBTU, in Southeast Asia it is $9/MBTU. At the time of writing, the cost of the US gas benchmark Henry Hub was $6.8/MBTU.

The Future of Energy

If everything is more or less clear with wind and solar energy (especially the growth rates of industries, investments in them and the development of related technologies), then everything is still more complicated with “green” hydrogen. According to it, a large-scale practical base for production and use has not yet been built up. At the same time, experts are sure that hydrogen will play the leading role in phasing out gas.

“Green” hydrogen will play the leading role in phasing out gas

Its main advantage is the ability to deliver to the very “bottlenecks” of infrastructure in Central Europe, which are the most vulnerable today, since these countries built their national power plants tied to pipes coming from Russia. Thus, REPowerEU aims to produce 10 million tons of hydrogen within the EU by 2030 and import the same amount.

The double plus is that the projected growth in green hydrogen production will also provide an opportunity to create new jobs and retrain the existing workforce. For the economies of Central and Eastern Europe, which are now on the verge of recession, this may be more than relevant.

In addition, hydrogen and its derivatives (such as synthetic fuels) will also help reduce CO2 emissions from maritime, aviation and heavy-duty land transport.

Today, more than 100 projects to trade hydrogen (or its derivatives such as ammonia and synthetic fuels) are being developed around the world, about half of them based in Southeast Asia. If all these projects are implemented, the equivalent of almost 5 million tons of hydrogen could be sold by 2030.

At the same time, it is important to understand that this market is only being formed. For its normal functioning, an adequate infrastructure for export-import, the stability of supplies and the commercial availability of technologies are needed. Significant investments are also needed across the entire value chain, including renewable energy capacity, hydrogen transport and storage infrastructure, and manufacturing capacity for key technologies such as electrolyzers and fuel cells.

It is difficult to reconstruct the logic of the Russian leadership, which in 2022, simultaneously with the Ukrainian one, decided to open the energy front, which, along with several packages of sanctions against Moscow, led to the largest global energy crisis in decades.

Perhaps the calculation was that the Europeans are still far from the finish line of the energy transition, which was supposed to take many decades (perhaps the planned date – 2050 – could create such a false impression).

In reality, as we have seen, the transition to renewable energy became a strong trend long before the Ukrainian war, and it is explained not only and not so much by abstract ethical or environmental considerations, as it might seem to an outside observer, but literally by economic ones. Switching to biofuels, wind and sun (and, in the future, to "green" hydrogen) is getting cheaper and more convenient.

Switching to biofuels, wind and sun is getting cheaper and more convenient

None of these long-term trends will ever be reversed. On the contrary, it can be assumed that, in fact, Russia's actions became their catalyst. Without energy blackmail from the Kremlin, the abandonment of hydrocarbons would have been much slower and the process could indeed have been delayed, which would have given Russia itself enough time to rebuild its own energy sector – and economy.

Green energy in Russia

As for Russia itself, until February 2022, projects in the field of green energy were seriously discussed in the business community. Seriously looking for foreign partners. For these purposes, they even prepared a special “taxonomy” – a list of domestic promising projects in the field of ESG.

Of course, "green" projects in Russia have always been assigned the role of additional to existing oil and gas projects. And the main interest of investors was concentrated, albeit in new, but adjacent to traditional areas. For example, there was a lot of talk about "blue" hydrogen (produced by steam reforming of methane, subject to carbon capture and storage).

However, in reality, the lion's share of Russian progress in the "green" direction was a forced measure, an irritated reaction to the demands of Western counterparties and the introduction of new environmental restrictions.

Now, Russia is unlikely to have funds that could be invested in capital-intensive projects in the field of renewable energy. Moreover, the country's leadership itself gives quite clear signals about its attitude towards them.