On the morning of June 24, 1905, a Japanese squadron of 53 ships approached the rocky, densely forested coast of Aniva on the southern side of Sakhalin, which began the landing of the 14,000th assault force of the 15th division. Only 1,500 soldiers and four militia squads, consisting mainly of exiled settlers and convicts, could resist her on the island. The fact that these people belonged to the squad was indicated only by a militia cross cut out of tin on the crown of their captive caps.

This day opened the final stage of the Russo-Japanese War. Its first weeks and the enthusiasm that swept the nation at the beginning of the "small victorious war," as Minister of the Interior Plehve hastened to call it, are far in the past. In February and March 1904, all the shop windows were full of popular prints depicting the Japanese in the form of macaques, or at least some frightened scumbags, who were beaten with whips by brave, huge Cossacks. Huge demonstrations took place in large cities (although their leaders were often identified as disguised police officers and police officers). The patriotic audience demanded the performance of "God Save the Tsar" three or four times during any theatrical performance. In those first weeks of the war, even newborns were often given the name Bronenosets, after Russian warships.

The enthusiasm that swept the nation at the beginning of the “small victorious” war is far in the past.

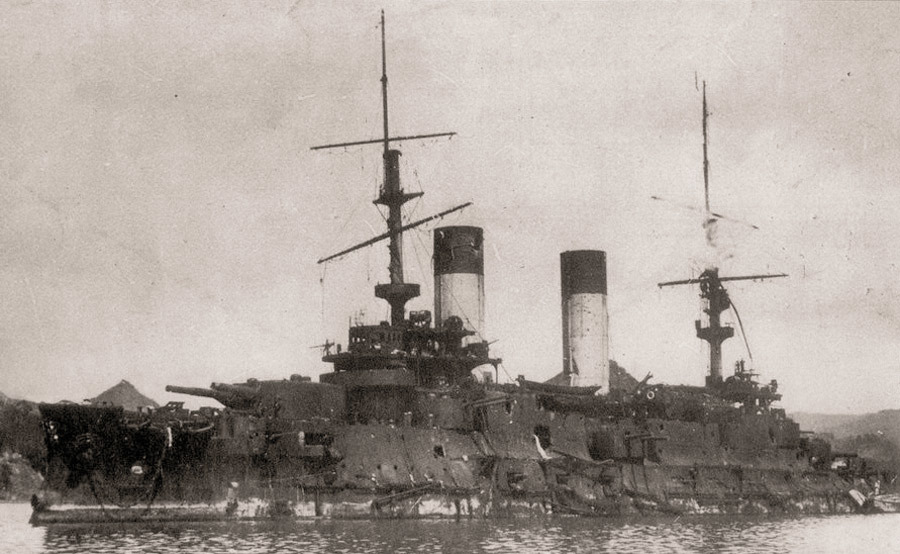

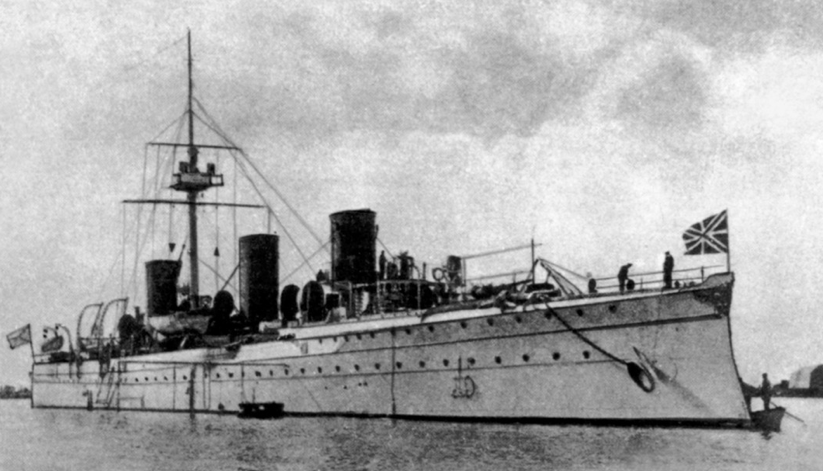

Months passed, one defeat followed another, it became clearer that this war, "incomprehensible for its uselessness", according to the writer and military doctor Vikenty Veresaev, would result in a serious disaster for Russia. The predominance at sea, which Nicholas II considered the most important task, quickly came to naught. The sudden attack of the Japanese fleet on the Russian squadron on the night of January 27, 1904 disabled several of the strongest ships, the pride of the Russian fleet – the Tsesarevich, Retvizan and Pallada. The Japanese landed in Korea. In May, while the Russian command was inactive, they landed on the Kwantung Peninsula and cut off Port Arthur's communications with Russia. The Port Arthur garrison surrendered in December 1904 after several months of siege. The remains of the Russian squadron in Port Arthur were sunk by the Japanese or blown up by the crews themselves.

This war, "incomprehensible for its uselessness", will result in a serious disaster for Russia

In February 1905, the Japanese forced the Russians to retreat in the pitched battle of Mukden. When on May 15, 1905, the Japanese in the Battle of Tsushima defeated the Russian squadron deployed from the Baltic, the outcome of the war was determined.

Popular discontent grew, which in the near future was to result in a revolution. After the fighting in Manchuria – "a bloody fog … corpses, corpses, corpses," according to Veresaev, mobilization took place like a hurricane throughout the country, which was supposed to compensate for the losses. The peasants had just been lamenting about soaring prices and higher taxes, when the ruthless mobilization machine reached them too, with "instantaneous snatching out of business at full speed, without the possibility of somehow closing and finishing their affairs."

The peasants had just lamented the soaring prices, when the ruthless mobilization machine reached them

After the brutal defeat of Admiral Rozhdestvensky's Baltic squadron in the Battle of Tsushima, the last thing Japan had to achieve was to gain control of Sakhalin. Among other things, this would allow her to conclude peace on more favorable terms.

“Nobody needs or is interested in Sakhalin,” Chekhov’s friend and publisher Alexei Suvorin remarked when Chekhov announced plans to visit the “convict island.” Serious defense of the extremely remote "convict island", sparsely populated, with harsh nature and practically absent communications, was not planned. Intelligence reports regarding Japanese plans for an attack on Sakhalin received little attention.

It was assumed that 1.5 thousand soldiers and six guns would defend it in the event of a Japanese attack. The plans included creating teams of hunters, exiled settlers and directly from convicts, with a total number of 3 thousand people. The corresponding order was given at the very beginning of the war by the governor in the Far East, E. I. Alekseev. The government promised food allowances and a reduction in the term of exile and imprisonment. These conditions attracted many settlers and prisoners to the squads.

The government promised food allowance and a reduction in the term of exile and imprisonment

The combatants were armed with Berdan rifles, or simply Berdans, which were supposed to carry 340 rounds of ammunition. There were no uniforms for them. The only thing that distinguished the combatants from the civilian population were the so-called "militia crosses" on their caps. Yes, and these were no longer those beautiful brass crosses that were introduced for the militia warriors in 1812. The crosses for the Sakhalin militias were roughly hewn out of tin during the hurried preparations for the defense.

If you remember who these people were and how they lived, it becomes clear that one could hardly expect sacrificial service from them to the king. Basically, they were murderers sentenced to life imprisonment. Initially, these convicts, participants in an experiment on the “Australian model”, which, as the authorities hoped, would help reduce the crime that jumped after the abolition of serfdom, traveled to Nikolaevsk on foot through Siberia, which took up to 14 months. Subsequent, a thousand a year, were delivered to Sakhalin by sea, and they spent 2-3 months in the holds shackled.

For the first three to five years on Sakhalin, they worked mainly in the coal mines, shackled in hand and foot shackles and sometimes chained to a wheelbarrow. 30-50 people lived in barracks with an earthen floor. Those who committed new crimes in prison were executed by the executioner – also from the convicts. Those who served hard labor were sent to the settlement. They were assigned a plot in the remote taiga, and with an ax, a shovel, a hoe, two pounds of rope and a supply of provisions for a month, issued at state expense, the special settlers set off to develop it and build a house for themselves. Since there were ten times fewer women convicts on Sakhalin than men, when they were transferred to the settlement, without asking consent, they were assigned as wives to those exiles who distinguished themselves by the most exemplary behavior. For exemplary behavior, the exiles were helped to acquire a household: they gave a cow and seeds at public expense.

However, agriculture in the harsh land was slow, and rich natural resources did not bring income to the island due to technological backwardness, lack of labor and corruption of officials. Although it was assumed that the exiles would remain on the island forever and its population would constantly grow, they fled from the island at the first opportunity.

One could hardly count on the loyalty of such a militia contingent. Their military training was entrusted to the heads of the prison department, since the officers for the new squads arrived on Sakhalin only in April 1905. Of the 2,400 exiles and convicts who initially signed up for squads, more than half had simply dispersed by the start of hostilities. With such forces, the defense of the island was impossible. It is believed that the military and administration from Sakhalin were not evacuated only because they were afraid to show weakness.

It remained to make the calculation that the soldiers left on Sakhalin would conduct partisan activities together with the militias, although no specific plans were developed in this regard.

Five partisan detachments, about 200 people each, which also included sailors from the flooded battleship Novik, were assigned areas of operation and warehouses were created for each of them in the taiga. After a short resistance to the many times superior forces of the Japanese landing force, the Russian detachments retreated into the taiga.

The military governor of Sakhalin Lyapunov (a lawyer in the prison department, far from military affairs) and the troops subordinate to him capitulated on July 19. The main forces of the island's defenders, led by Colonel Artsishevsky, were also surrounded, partially killed, and partially surrendered. Upon learning of this, the detachment of Captain Dairsky, who was trying to break through to them, changed plans and for some time continued to operate independently in the valley of the Susui and Naiba rivers, but was also defeated. Arkhip Makenkov, the engine driver from the Novik, told about his fate, who witnessed the death of the detachment. According to Makenkov's report, Dairsky was captured along with the wounded, from whom he refused to leave, and the Japanese were able to lure the rest of his detachment out of the forest with the help of the wounded, who were forced to shout "Russians, come out, nothing will happen to you!" Makenkov and one of the militia convicts did not give up and secretly followed the detachment 12 miles to the place of his execution, which Makenkov described in his report.

Makenkov himself is considered the last defender of Sakhalin. After the death of the Dairsky detachment, he went to look for another detachment to which he could join, but did not find anyone. Makenkov wrote:

“I don’t remember how long I went without food. Bypassed the villages. Not far from Leonidovo I came across a tent with two Japanese sappers and an engineer officer. When they fell asleep, they were slaughtered. I took a paper blanket, a compass, a map, matches, canned food, arisaka and a pistol with binoculars … "

On October 20, 1905, Makenkov entered the northern part of Sakhalin, which remained under the control of Russia.

Correctly assessed the situation and made the right decision only one detachment of militia led by Captain Bykov. Having learned about the surrender of the main forces and the governor of the island, Bykov decided to take his detachment to the mainland. They captured eight Japanese kungas fishing boats and attempted to moor to the mainland, which they failed due to a storm. Having moored back to the coast of Sakhalin, they found a guide who, in seven days, brought them through the taiga to Cape Perish. There Bykov hired a gilyak (a representative of the indigenous Far Eastern people), who, with several combatants, was sent to the mainland through the Tatar Strait. A ship that arrived from Nikolaevsk a few days later evacuated 203 people who by that time were with Bykov. These soldiers, sailors and militias marched through the taiga for a total of about 900 kilometers.

On August 23, 1905, the Treaty of Portsmouth was signed, and South Sakhalin became Japanese until 1951. Militia tin crosses are found by modern search enthusiasts in the taiga, in places of past battles or executions, along with shell casings, remnants of equipment and bones. They are sold to collectors on various specialized sites, where the price of a tin militia cross from Sakhalin, due to its rarity, is even higher than the price of a brass one.