How the fight against AIDS began in Russia

“A person, sensing some incomprehensible danger, goes today to Sokolinaya Gora, to the address published by the media,” Ogonyok magazine wrote in 1987. Here, on the basis of the Infectious Diseases Hospital No. 2, after the discovery of the first HIV-infected person in the USSR, a citizen of South Africa, a room for anonymous HIV diagnostics, working on a voluntary basis, appeared. Reception in the office of confidence was conducted by the President of the Academy of Medical Sciences of the USSR, Professor Vadim Pokrovsky. Under his leadership, they began to create laboratories for the diagnosis of HIV throughout the country – by the end of 1986 there were about a hundred of them. Pokrovsky called risk groups visiting students and people registered in narcological and skin care dispensaries. “We are waiting for active assistance from the police to identify centers of drug addiction, prostitution and homosexuality,” the professor said then.

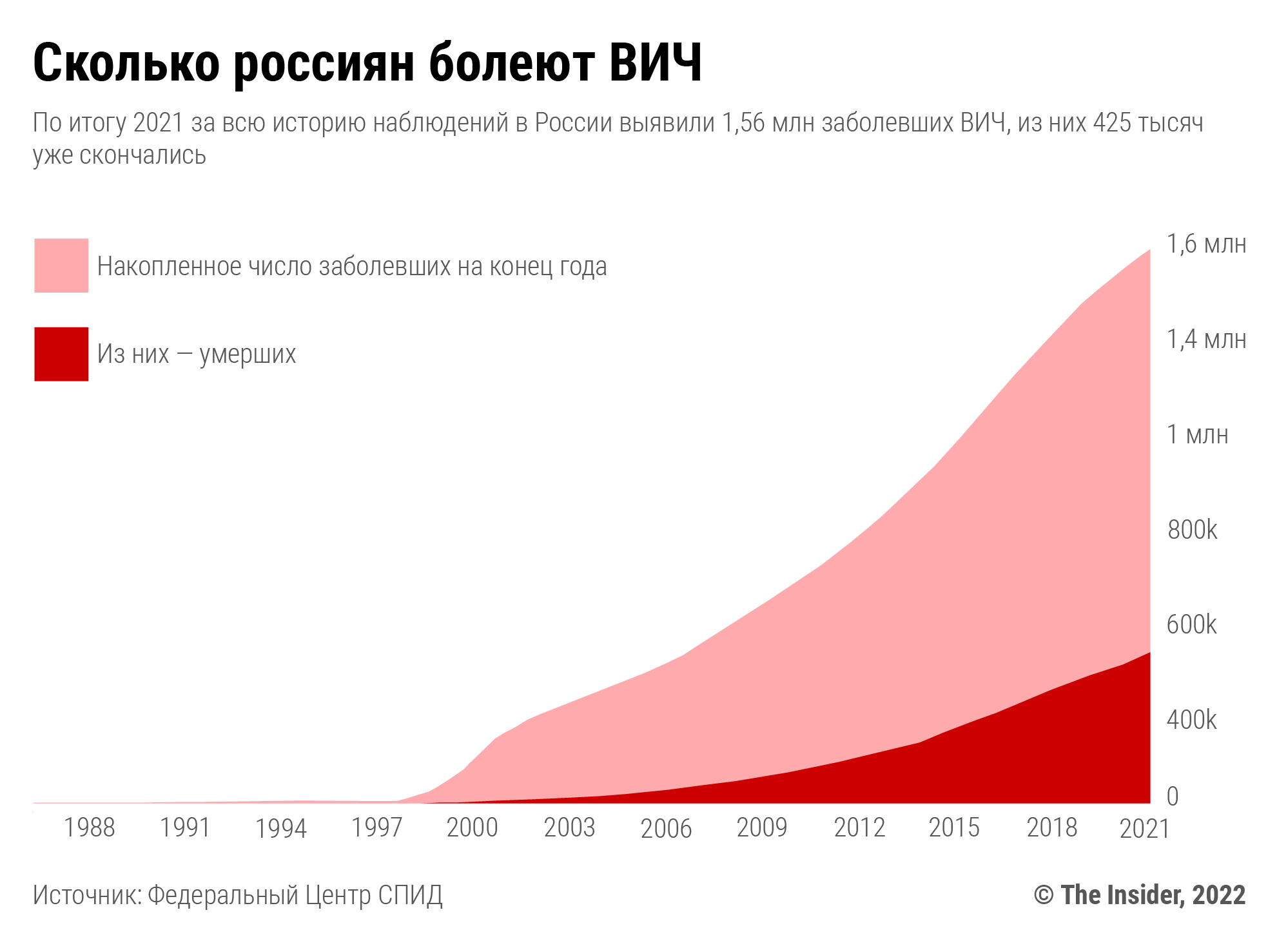

Pokrovsky from the very beginning demanded that the state allocate money for prevention and medicine for the sick, warning that without these measures, an epidemic awaits Russia – but until today, his alarmist moods in the Ministry of Health are not supported, although Russia has long been close to Equatorial Africa in terms of infection rates .

Literally in a couple of rooms, Pokrovsky managed to collect enough equipment and reagents to qualitatively – by the standards of that time – diagnose HIV. Students worked in the laboratory, they did not receive money for this. It was here that the first-year student of the Dental University (MMSI named after Semashko) Aleksey Mazus came (years later, a line will appear in his official biography that he allegedly founded this laboratory). Later, Mazus created the AIDS Prevention Center – "Anti-HIV". It is difficult to say what exactly this center was doing in the 1990s – the center's activities were not covered in the media, only occasionally one could come across some statements by Mazus, such as that the existing laws, they say, protect the rights of HIV-infected people too much. Later, Mazus re-registered the SPID.Ru domain to his company, the only Runet site at that time that talked about HIV and AIDS. And by the early 2000s, he had already made enough friends with the Moscow government for his center to become associated with a state organization. After that, Mazus began an active PR campaign and became a permanent main speaker on HIV in the Russian media.

Artificial shortage of drugs

In 2000, Mazus reassured the Russians: “The peak of the epidemic in Moscow came in 1999. <…> The epidemic is under the watchful eye of physicians and scientists.” In reality, Russian state medicine not only failed to curb the epidemic, but also poorly understood how to deal with it, opposing infection control programs popular in Western countries among injecting drug users. In 2002, the American newspaper The Wall Street Journal described the situation in Russia as follows:

“Many doctors in positions of power today were educated under the authoritarian Soviet public health system. They disagree with Western methods of treating drug addiction and controlling the spread of HIV infection, especially needle replacement programs that provide clean needles to drug addicts free of charge, and methadone-based therapy. Some doctors, such as Alexei Mazus, director of the Moscow AIDS Center and one of Russia's most prominent AIDS doctors, oppose needle exchange programs. These doctors fear that such programs will encourage young people to become addicted.”

At that time, independent projects on HIV prevention among drug users were already operating in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Anastasia K., an HIV activist, recalls to The Insider:

“In Moscow in 1998, the program was launched by the Dutch branch of MSF. Both staff and volunteers were drug users, usually with HIV. A year later, they began to publish the most intoxicating magazine "The Brain", dedicated to everything related to drug use. So, in the late 1990s, two processes were going on on the streets of Moscow at the same time: activists talked about harm reduction, about the need to use clean needles, and police officers organized evening raids at pharmacies precisely on those who came for clean syringes. At the same time, antiviral therapy in the country was no longer enough for all the sick, it was rarely given out. It was a very dramatic time. It was on this wave that “drug addicts will not adhere to the regime” that in those years there were actions with chaining to fences and seizing the building of the Ministry of Health. The slogan “To live is our policy!” appeared, the people were very afraid of dying and demanded purchases and generics. It was possible to receive drugs only in a serious condition. At the same time, everyone knew that there was a cure.”

Aleksey Mazus, having already taken the post of head of the Moscow AIDS Center, openly told foreign correspondents that most likely they would not be able to prescribe antiviral therapy to drug users, the homeless and prisoners, among whom the infection spread very quickly through injections of artisanal drugs – supposedly they would not be able to adhere to the regime taking pills.

At the same time, the Ministry of Health preferred to buy the most expensive pills, and there was simply no production of drugs in Russia. In the early 2000s, the Ministry of Health simply did not respond to proposals from American funds to organize the supply of cheap generics to Russia and reduce the cost of treating each patient.

In the early 2000s, the Ministry of Health simply did not respond to US proposals to organize the supply of generics

Activists held actions in different cities of Russia, pointing to the almost complete lack of medicines in the country. The most notable organization was FrontAIDS – for example, in 2004 its members chained themselves to the doors of the Kaliningrad mayor's office, and in St. Petersburg they staged an action with coffins in front of Smolny.

Testing instead of prevention and treatment

In Russia, the prevention campaign was built mainly on the propaganda of diagnostics, and the same Aleksey Mazus became its main apologist. Test systems were purchased in huge quantities and tested not only for vulnerable groups, but for everyone else – first of all, donors, pregnant women and conscripts. This was the main part of the financing of the state program "Anti-HIV-AIDS", which, however, was underfunded in different regions by 50-95%. There was almost no money for the modernization of hospitals, the creation of special departments and, in the end, the purchase of medicines. “Instead of improving hospitals, the money was thrown at absolutely ineffective mandatory testing and so on. Our medicine was not ready for an epidemic, ” said a patient of the Moscow Anti-HIV program in an interview with the BBC. However, in the center of Mazus, on the contrary, they were proud of the fact that in Russia by the mid-2000s the level of examination was one of the highest in the world – 15-16%.

Most of the money from the Anti-HIV-AIDS state program was spent on mass tests instead of drugs

In 2000, 24.6 million HIV tests were carried out in Russia, which is almost 17% of the country's population. However, as follows from the report of the Federal Scientific and Methodological Center for the Prevention and Control of AIDS, more than a quarter of those tested were pregnant women and donors, another quarter were examined for clinical indications (mainly those who require tests for hospitalization), and 31% of the tests fell on the group "others" – who is included in it, the center does not disclose. However, among these groups, the proportion of detected infections was minimal – 0.01–0.12%. Risk groups – drug users, prisoners, men who have sex with men – were almost not examined, in total they accounted for less than 7% of the tests.

At the same time, every 20th drug user turned out to be a carrier of HIV, The Insider's calculations show. Information that the majority of infections (80–90%) were among injecting drug users was known to the supervisory authorities. Among prisoners, about 1% of those surveyed were infected – this is much more than in other surveyed populations (for example, among pregnant women or patients with sexually transmitted diseases).

For twenty years, the situation with testing has not changed dramatically – in Russia, all pregnant women, conscripts and people entering hospitals are still forcibly tested, although they are not at risk for HIV, and officials know that cases of infection among them extremely rare. At-risk groups, on the other hand, have become even less likely to come to the attention of a mass testing campaign.

The reason for this policy is the law adopted back in the mid-1990s to prevent the spread of HIV. Amendments to it, providing for general testing, were lobbied by manufacturers of test systems. Pokrovsky explained the situation around the bill to the Pravda newspaper as follows:

“After the adoption by the Duma in the first reading of the draft law <…> a struggle began around it. Actually, the whole discussion was only around two articles of the draft concerning the examination for antibodies to HIV. At the same time, the bill was attacked from two sides. The World Health Organization and various nongovernmental organizations associated with sexual minorities have criticized the project for retaining provisions for forced testing of certain populations and foreigners, seeing this as an attack on human rights. On the contrary, domestic manufacturers of test systems, who are interested in a huge state order, and many doctors, for whom human rights, against the backdrop of the abolition of constitutions and the dispersal of parliaments, could not but turn into an empty sound, demanded to expand the circle of people examined by force.

A more humane bill, which Pokrovsky's team had been developing since the early 1990s, did not reach the State Duma at all. “We started the process of writing a law on HIV in 1992, but our bill burned down in the White House when it was shelled [in 1993],” he said in an interview with Lenta.Ru. Pokrovsky declined to speak to The Insider about which companies lobbied for mass HIV testing in the early 1990s.

As a result of the approach approved by the State Duma, almost all funds allocated for the Anti-AIDS Federal Target Program (1993, 1996) were spent on the purchase of diagnostic test systems. In 1995, Pokrovsky complained about the situation to the Segodnya newspaper:

“What was the reason for such an “original” distribution of funds? And the fact that practically no one manages the implementation of the program as such. The money is transferred by the Ministry of Finance and spent by the Ministry of Health and Medical Industry according to the views of the administrators, and they are such that, first of all, it is necessary to support the manufacturers of test systems, that is, their own production. This is understandable, because about 10 thousand people are employed in this production, as well as directly in testing the population. At the same time, a lobby that would protect the interests of prevention does not yet exist.”

One of the main suppliers of tests was ECOLab LLC, founded in Elektrogorsk near Moscow by Seyfaddin Mardanly with the help of his acquaintances from the Ministry of Health. In the early 2000s, the market was re-divided. This is how Seyfaddin Mardanli describes the times when Yury Shevchenko became the Minister of Health:

“A new team came to the Ministry of Health, the functions of distributing state orders were taken away from the department of bacterial preparations and set their own conditions: a 20% cash kickback for distribution to someone else. They took everything from us in one fell swoop and gave it to others.”

In 2001, about which the founder of ECOLab speaks, the Ministry of Health indeed adopted a list of recommended test systems, and priority was given to the American manufacturer Bio-Rad. According to publications on tenders and then to the State Procurement portal, for a long time the Russian "daughter" of the company – Bio-Rad Laboratories LLC – was the leader in the supply of test systems to Russian hospitals and institutions. For example, in 2008, it supplied FMBA with equipment worth more than 387 million rubles, Rospotrebnadzor (in 2009-2010) – more than 100 million rubles (data from the public procurement portal).

Abstinence and braces instead of sex education

Supporting mass testing far beyond the risk groups, the Mazus Center simultaneously opposed educational programs that NGOs tried to implement with foreign grants. In 2005, in a team of other authors, in a report sponsored by the Moscow government, Mazus spoke negatively about sex education in educational institutions:

“The practically uncontrolled training of Russian youth in the framework of such programs on the basics of “safe sex” can serve as an example when a significant part of young people for whom risky sexual behavior is a way of life were “explained” that“ this trifle ”in the form of a widely advertised condom is actually an indulgence on free sexual relations.

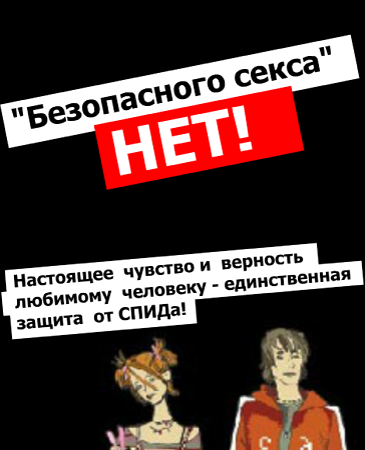

Condom advertising as a means of protection against infection at that time was indeed sponsored by international funds. For example, a series of commercials and posters with the slogan "Safe sex is your choice" and "This little thing will protect both" was made by a St. Petersburg advertising agency with money from the PSI international charitable foundation. “Interestingly, after the start of this program, there was a decrease in infection among the younger group of 16-20 years old,” an HIV activist who wished to remain anonymous told The Insider. At the same time, the Moscow authorities spent money on broadcasting commercials on the same channels and posting posters on the same walls with the slogans “A healthy family is protection against AIDS” and “There is no safe sex.”

“It was in Moscow that officials naturally hated the topic of “safe sex”, and in the city law “On HIV” No. 21 of May 26, 2010, the condom was awarded a separate stiff ban. Now “mechanical contraceptives” can’t be recommended for HIV prevention at the expense of the budget,” notes Anastasia K. This was the first such law adopted in the Russian region – before that, everyone was guided by all-Russian legislation. Moscow City Duma deputy Lyudmila Stebenkova was involved in its development – like Mazus, she is an opponent of condoms, homosexuals and international NGOs and a supporter of "family values".

At the federal level, the same policy was supported by the director of RISI, the analytical center of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service, Yevgeny Kozhokin, whose reports, in collaboration with Mazus, were regularly published on the Moscow portal SPID.Ru. Together they promoted the concept that abstinence and fidelity should be the foundation of HIV prevention. The authors did not hide that they got this idea from the US government. However, there she was repeatedly criticized by scientists and activists. In 2016, scientists from Stanford published confirmation of the harmfulness of this approach. They studied the behavior of residents of subequatorial Africa, where the US sponsored the same program, and found that the social advertising of fidelity and abstinence did not actually lead to a change in people's sexual behavior. The authors emphasized that the money spent on promoting abstinence and fidelity could be better used to promote other, more effective prevention measures.

Propaganda of the correct family values, apparently, did not help Russia much. Two-thirds of newly diagnosed patients as of 2021 suggest that they were infected during heterosexual contact. In the words of the federal AIDS Center, "HIV infection goes beyond the large reservoir" of drug users and homosexuals. At the end of 2020 in Russia, out of every 200 men aged 40–44 years, seven were HIV-infected, and on average up to 1.5% of adult Russians have HIV (in some regions and cities of the Urals and Siberia, the proportion of carriers is above 3% ). For comparison, in the countries of southern Africa, this figure exceeds 10%, and doctors observe figures comparable to Russia in the countries of Equatorial Africa – for example, in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea. In the US, this figure is four times lower, in Portugal, which faced a heroin epidemic in the 1970s and 80s, it is three times lower than in Russia.

In total, according to Rospotrebnadzor, from 1987 to 2021, more than one and a half million cases of HIV infection were detected in Russia, more than a quarter of these people have already died.

One of the main reasons for this situation in Russia is the large number of people who inject drugs, points out the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS. Its guidelines state that Russia, along with the US, China and Pakistan, accounts for half of all people in the world who inject drugs, and every 4 minutes one such person in the world becomes infected with HIV. It is harm reduction programs – the distribution of syringes and condoms, as well as treatment with naltrexone and substitution therapy – that the UN program calls a way out of the situation. Such measures are being taken in China and the United States, but in Russia the state does not introduce such practices, substitution therapy is prohibited, and NGOs working with vulnerable groups (for example, the Andrey Rylkov Foundation, Humanitarian Action, Svecha, Phoenix PLUS and dozens of others) are regularly recognized as "foreign agents". Похожая ситуация в Пакистане , где политики противостоят использованию практик заместительной терапии и уменьшения вреда, а уязвимые группы (наркопотребители, секс-работники) криминализованы.

ВОЗ указывает на программы сексуального просвещения, обучения пользованию презервативами и предоставления стерильных шприцев как главные меры по противодействию распространению ВИЧ, вирусных гепатитов и венерических заболеваний. Тестирование, которое продвигал Мазус, также входит в список ключевых мер, одобренных ВОЗ, однако, в отличие от России, с акцентом на уязвимые группы. Пропаганда верности в меры, одобренные международной организацией, не входит. ВОЗ также рекомендует правительствам инвестировать в борьбу со стигмой, насилием на гендерной почве и за гендерное равенство.

В России же склоняются к противоположным мерам: стигматизируют однополый секс, а пострадавшие и правоохранители, согласно недавнему исследованию проекта «Правовая инициатива», не воспринимают сексуальные домогательства всерьез.

«Безопасного секса не бывает». Пропаганда верности за госсчет

Сделав поголовное тестирование на ВИЧ главным оружием государства против эпидемии, Алексей Мазус и его знакомые решили также заработать на социальной рекламе против СПИДа. ООО «АнтиВИЧ-Пресс», открытое при помощи рекламщика Ильи Цигельницкого, стало получать госзаказы на социальную рекламу против СПИДа. Руководителем компании стала Александра Ускова — через несколько лет она возьмет фамилию Мазус. Фирма позиционировала себя как «первопроходца отечественной социальной рекламы», хотя подобная реклама была как на ТВ, так и в газетах и до нее. Принадлежащий «АнтиВИЧ-Пресс» сайт SPID.Ru публиковал ролики и флеш-баннеры о том, как важна верность партнеру для защиты от СПИДа и какое зло наркотики.

Сайт выглядел ассоциированным с правительством Москвы и Алексеем Мазусом лично. На нем публиковались статьи Мазуса с одинаковым посылом — нужно проверять как можно больше россиян на ВИЧ, а спастись от эпидемии поможет только здоровый образ жизни и отсутствие случайного секса. В публикациях , к которым прикладывал руку Мазус, утверждалось, что презервативы не защищают от ВИЧ:

«Я выбираю безопасный секс» — этот рекламный ход придумали производители презервативов, чтобы создать иллюзию безопасности случайных половых контактов, а это значит продавать всё больше и больше своих резиновых изделий. <…> Безопасного секса — не бывает! Дорогой выпускник, избегай случайных половых связей».

Утверждение из данного обращения опровергают ученые, например, американский вирусолог Егор Воронин, который больше двадцати лет занимается исследованиями ВИЧ и перспектив изобретения вакцины от него:

«Никакие страшилки не удержат тинейджеров от секса. Упор, несомненно, следует делать на популяризацию презервативов, которые при правильном использовании являются наилучшей защитой от ВИЧ».

Правильно использовать презерватив тоже надо уметь, и в некоторых странах (например, в Западной Европе, в странах Африки) этому обучают в школе на уроках полового просвещения. В России в 90-е годы половое воспитание начинали вводить как специальные уроки в рамках занятий по биологии, но сегодня они запрещены. Согласно метаисследованию ЮНЕСКО, школьные программы, которые пропагандируют воздержание в качестве главного подхода к борьбе с ВИЧ, другими инфекциями и нежелательной беременностью, не приводят к искомым результатам. Наиболее эффективными оказываются школьные программы с фокусом на более позднее начало половой жизни с обучением пользованию презервативами и другими средствами контрацепции.

Центр Мазуса заказывал рекламу у дочерней компании не только для своего сайта, но и для телевидения. К середине 2000-х ролики стали еще более агрессивными — в них появились громкие слоганы вроде «Пропаганда порока царит в эфире и в твоей голове» с видеорядом из полуобнаженных девушек и выползающих из головы молодого мужчины жуков, или «Что бы нам ни внушали продвинутые друзья, случайные связи — это просто искаженное желание обменяться энергией, найти понимание, любовь и тепло, в котором мы все так нуждаемся» с видеорядом из говорящей человеческим ртом ладони и снова танцующих полураздетых девушек, заманивающих мужчин в постель.

Реклама, пропагандирующая в первую очередь верность, размещалась на московской вещательной сетке ТВ и призывала регулярно делать тесты на ВИЧ всё в том же центре на Соколиной Горе. В интервью «Московскому комсомольцу» в 2003 году Мазус хвалился тем, что у москвичей есть доступ к правильной информации:

«У нас есть горячая линия, плакаты на улицах. Но ролики по телевизору, где парень с девушкой только познакомились, а он ей уже презерватив сует, я запретил — это пропаганда свободной любви, а не борьба со СПИДом. Теперь в них просто рассказывают, как спастись от инфекции».

Продвигала созданные «АнтиВИЧ-Пресс» материалы и Людмила Стебенкова. Во сколько такая реклама обошлась Москве и Минздраву России, сказать сложно: открытой системы гостендеров в те годы не существовало. The Insider удалось найти данные нескольких московских тендеров на просветительские мероприятия по программе «АнтиВИЧ/СПИД» в 2005–2006 годах, из них следует, что столица выделяла тогда на эти меры примерно по миллиону долларов в год.

Всего на такую рекламу и соответствующие листовки в 2002–2006 годах правительство закладывало 217 млн рублей (более $7,5 млн), причем большая часть финансировалась из федерального бюджета — в то время как почти всё бремя обеспечения лекарствами легло на региональные бюджеты и часто было недофинансировано.

Государство тратило десятки миллионов на пропаганду верности, а бремя обеспечения лекарствами ложилось на региональные бюджеты

Через несколько лет дочерняя компания центра Мазуса полностью перейдет под контроль Александры Мазус. В 2020 году налоговая признала «АнтиВИЧ-Пресс» недействующей компанией, а в 2022 году Александра Мазус начала процедуру ее ликвидации.

Минздрав против презервативов и за красивую статистику

В 2010 году Алексей Мазус стал главным внештатным специалистом Минздрава России по ВИЧ — под него эта должность и появилась. На новом посту он постарался приложить руку к клиническим рекомендациям по лечению ВИЧ — они описывают действия врачей на протяжении всего процесса взаимодействия с инфицированными, начиная с диагностики и заканчивая рекомендованными схемами препаратов.

Пришествие Мазуса произошло на фоне скандала вокруг Федерального центра СПИД, руководителем которого был (и остается) Вадим Покровский. К этому времени позиции Мазуса и Покровского, которые когда-то вместе начали борьбу против распространения ВИЧ в Советском Союзе и России, разошлись уже довольно сильно: если первый заявлял о том, что в стране лекарств хватит на всех, а рост числа заражений успешно сдерживается, то второй — о том, что Минздрав занижает цифры по заболевшим, а лекарств катастрофически не хватает.

По данным газеты « Ведомости », поводом для проверки центра нелояльного Минздраву академика Покровского в 2010 году стало обращение депутата Мосгордумы Людмилы Стебенковой, давней соратницы Мазуса. Появлялись даже предположения, что подконтрольный Роспотребнадзору Федеральный центр СПИД возглавит Мазус, но этого не произошло. Вот как описывает то время ВИЧ-активистка Анастасия К.:

Когда Вадим Покровский после проверок остался руководить Федеральным СПИД-центром, все даже немного удивились. К тому времени его деятельность стала чистой фрондой, и сейчас существуют две «Вселенные ВИЧ в России» — его и Мазуса. Федеральный СПИД-центр старается придерживаться точной статистики и регулярно выдает информационные бюллетени, в которых упоминаются и самые пораженные регионы, и рост новых случаев, и даже рост инфицирования при грудном вскармливании на Кавказе. Мазус же утверждает, что нет никакого роста новых случаев, а есть «тесты, зафиксированные дважды». Покровский пишет о снижении тестирования среди наркопотребителей и МСМ <мужчин, имеющих секс с мужчинами — The Insider> , Мазус рапортует о самых высоких показателях по тестированию в мире. Покровский говорит в интервью о презервативах и заместительной терапии, Мазус любит вставить к месту и не к месту «безопасного секса не бывает». Как они уживаются в соседних зданиях — непонятно <имеются в виду корпуса инфекционной клинической больницы № 2 в Москве, однако примерно в 2020 году центр Покровского переехал и расположен теперь по другому адресу — The Insider> .

Став главным специалистом страны по ВИЧ, Мазус, как и прежде, делал удобные Минздраву заявления о том, что распространение ВИЧ в России стабилизировалось, вторя ответственным чиновникам министерства, которые не упускали возможности отметить, что в России ситуация лучше, чем в США или Европе, что полностью противоречило официальной статистике.

После появления в Минздраве главного внештатного специалиста по ВИЧ на сайте министерства обосновались статьи о том, что презерватив не защищает от инфекции. Активисты даже запустили интернет-петицию против публикаций на сайте министерства. Этим фактом возмущался и Вадим Покровский:

До недавнего времени на сайте Минздрава висели материалы о том, почему не стоит доверять презервативам. Потребовалась острая критика, чтобы всё это убрать. В качестве альтернативы некоторые предлагают хранить верность партнеру. В результате крестового похода за нравственность депутата Мосгордумы Людмилы Стебенковой на телевидении исчезла реклама презервативов, а сами средства выросли в цене до 600 рублей за десяток. Как думаете, многие готовы выделять на эти цели такие деньги? Так что нам стоит подумать хотя бы о том, как остановить рост цен на эти изделия.

Мутные контракты на социальную рекламу

Одновременно ведомство стало заключать подозрительные контракты на социальную рекламу и опросы в этой сфере. Условия исполнения контрактов, заявляемые Минздравом, были невыполнимы по срокам: фактически победителям конкурса в конце года предлагалось освоить за 1–2 месяца сумму на пропаганду против ВИЧ, рассчитанную на год. Кроме того, при выборе победителя предпочтение отдавалось компаниям, которые предлагали стоимость выше, чем у конкурентов.

The Insider нашел несколько таких контрактов, заключенных в 2011–2012 годах. К примеру, в 2012 году в октябре был заключен контракт на телерекламу до конца года на 6 млн долларов. А в 2011 году деньги ушли на продвижение нового сайта Минздрава по борьбе с ВИЧ — уже через несколько месяцев он был заброшен, перестал обновляться. Отпечатанные по итогу конкурса брошюры также не дошли до граждан — контракт не подразумевал их логистику, а новый контракт для этого заключать не стали.

Тогда же на некоторые из них обратили внимание проект Алексея Навального «Роспил», правозащитная организация «Агора» и Общественная палата, после чего Генпрокуратура направила следователям материалы для заведения уголовного дела.

Уход и второе пришествие Мазуса

Занимая должность главного внештатного специалиста по ВИЧ, Алексей Мазус вместе с группой московских врачей-инфекционистов создал в 2014 году новую организацию, на этот раз некоммерческую: Национальную вирусологическую ассоциацию (НВА). Ее приоритетной задачей стала разработка рекомендаций по диагностике и лечению ВИЧ. Хотя в 2013 году в России вышли первые официальные клинические рекомендации по лечению и диагностике ВИЧ, в 2014 году они были переизданы уже под брендом НВА. Мазус был руководителем команды составителей рекомендаций в обоих случаях. Получала ли ассоциация от Минздрава деньги за разработку рекомендаций, неизвестно.

Примечательно, что в этих рекомендациях игнорировалась единственная на тот момент отечественная разработка — антивирусный препарат фосфазид, который уже много лет входил в список жизненно важных лекарств (ЖНВЛП), однако рекомендовалось использовать в первую очередь тенофовир, который в ЖНВЛП не входил. Фактически, когда какое-то лекарство не входит в список ЖНВЛП, больницы и департамент здравоохранения реже закупают его, а цены на него могут быть значительно выше. Производители фосфазида тогда сталкивались с давлением со стороны конкурентов, рассказывал академик Покровский.

В 2015 году пост главного внештатного специалиста Минздрава по ВИЧ занял врач-инфекционист Евгений Воронин. При нем была принята государственная стратегия борьбы с ВИЧ до 2020 года, Минздрав стал вести переговоры с поставщиками о снижении цен (и за пять лет добился снижения стоимости популярных схем в 10 раз). Под руководством Воронина были разработаны новые клинические рекомендации. Российский препарат фосфазид, проигнорированный в рекомендациях Мазуса, попал в несколько схем, рекомендованных в первую очередь. Воронин постарался добиться включения в ЖНВЛП современного препарата тенофовир (его как раз рекомендовали в качестве приоритетного лечения еще при Мазусе), но комиссия министерства отказала в этом.

Внезапно в середине 2020 года Минздрав сообщил, что Воронин больше не будет главным внештатным специалистом министерства по ВИЧ и на эту должность возвращается Алексей Мазус. Никакого специального объявления этого события не было — просто в одном из рядовых пресс-релизов ведомство упомянуло , что теперь эту должность занимает Мазус. Произошло это на фоне начала подготовки новой стратегии противодействия распространению ВИЧ-инфекции, рассчитанной до 2030 года.

Одновременно с этим активизировалась Национальная вирусологическая ассоциация Мазуса. Если после публикации рекомендаций от 2014 года ее сайт был заморожен, то теперь он был перезапущен на новом домене. На нем тут же был размещен разработанный ассоциацией вариант новых клинических рекомендаций.

Фактически первое, что сделал Мазус, вернувшись в Минздрав — это продвинул препарат «Элпида», производителем которого является спонсор его ассоциации. При этом из рекомендаций исключили информацию о взаимодействии с десятками других лекарств, представив его более безопасным и предпочтительным для назначения, чем другие препараты. На тот момент «Элпида» было самым дорогим средством от ВИЧ (6545 рублей за месячный курс , на 7% дороже, чем «Тивикай» — один из лучших на тот момент препаратов). Но цена нового препарата не самое страшное. Куда страшнее то, что он оказался почти не испытан на людях. Однако на его закупки государство уже тратит сотни миллионов рублей ежегодно.

Подробнее о том, как Мазус заработал на лекарстве с сомнительной эффективностью, читайте в материале «Казус Мазуса» .

В работе над материалом использованы архивные публикации в российской прессе. Полные тексты этих публикаций, финансовые отчеты и учредительные документы организаций, упомянутых в расследовании, вы можете найти на Github . Автор благодарит экспертов, пожелавших остаться анонимными, за участие в подготовке материала. Для оформления статьи использованы иллюстрации, созданные с помощью нейросети DALL·E 2. В коллаже использованы фрагменты рекламных роликов и постеров депздрава Москвы и вырезки из российской прессы.