Not only male protests

Women in the Middle East were not as politically passive as many might think. Revolutionaries and reformists have been at the center of most historical sociopolitical movements in the Arab countries, Iran and Turkey. Women belonging to different classes, religions and ethnic groups were a significant force in the resistance to dictators. They formed trade unions and fought for workers' rights against discriminatory laws. In the 19th century, urban and peasant revolts were the main political arena available to the majority of the population, and it was here that women played a significant, albeit poorly documented, role in the political history of their countries and communities.

Throughout the 19th century, the states of the Middle East developed and strengthened the apparatus of centralized power: the bureaucracy, taxes, the army and the police. In Egypt, this led to dozens of uprisings by peasants and urban artisans, from whom the state often tried to create a productive workforce by violent means. Thus, for example, the decision of Muhammad Ali of Egypt (viceroy of Egypt) to confiscate the grain harvest caused powerful protests in 1820-1821. Some 40,000 peasants, including women, supported an independent government in Qena province. During urban riots, women fought against Mamluk soldiers: they took up positions on top of the barricades and threw stones while the men charged.

During urban riots, women fought against Mamluk soldiers: they took up positions on top of the barricades and threw stones while the men attacked.

Officials of the period viewed the propensity for resistance and rebellion, especially among working-class women, as a separate issue. In 1863, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire came to visit Cairo, then under imperial control. The authorities took care of the safety of this meeting in advance, ordering all women of the “lower classes” to stay at home during the visit. They worried that "Arab women are frank and direct and can shout out their complaints and grievances."

Throughout the 19th century, on the territory of the modern states of the Middle East, resistance to central authorities, as a rule, foreign or under foreign influence – European or Ottoman, did not subside. After the suppression of Urabi's uprising against foreign influence (1879-1882), the authorities began to consider women participating in it on an equal footing with men. They were also tortured and imprisoned on charges of looting and rebellion.

Later, mass riots were replaced by the era of the formal political arena, and the protest against colonialism and the development of nationalism became the lot of educated elites, and women were excluded from the formalized sphere of politics.

20th century: Beginning of women's movements in Iran

Early women's movements emerged in Iran during the Constitutional Revolution of 1906–1911. At that time, the country was experiencing a sharp economic and cultural decline. The extravagance of the Shah dynasty became a particularly acute problem during the short reign of Mozaffar al-Din Shah Qajar. The Shah borrowed heavily from the Russian Empire and Great Britain to afford his luxurious lifestyle, as well as cover government expenses. The protests turned into a revolution, which resulted in the creation of the Majlis and the adoption of a constitution that limited the activities of the Shah. The constitutional movement brought together people from different ethnic and religious groups in Iran, belonging to various political camps: from socialists to liberals, from the Shiite clergy to secularists. Among them were women. They formed semi-secret associations, the anjumans, which functioned de facto as revolutionary cells. The largest of them included about 60 women. Their goal was to pool strength and resources, share information, get more women involved in politics, and increase support for the constitution. Over coffee and hookah, the women discussed the advantages of constitutionalism and the disadvantages of authoritarianism.

The constitutional movement advocated the need for public welfare, state general education, institutions of justice and honest courts, equality, the protection of the right to life, property and freedom through secular law and the establishment of a democratic parliamentary government that would limit the powers of the Shah. Women's rights were an important part of these demands.

The Iranian women used all the methods available to them to achieve their goals. In newspapers, they used quotations from religious texts to justify their calls for equal treatment of women. Iranian women protected fellow constitutionalists from the Shah's forces during demonstrations and even used their connections with women in the Shah's harem to get information about what was going on behind the scenes of the monarchy. Clothing gave Iranians anonymity and they could secretly pass messages and weapons between revolutionary cells. Also, in order to achieve their goals, they staged boycotts of foreign goods and services, for example, they refused to use imported fabrics. They believed that this could free Iran from dependence on European merchants and manufacturers.

Clothing gave the Iranians anonymity, and they could secretly pass messages and weapons between revolutionary cells.

In addition to the adoption of the constitution, one of the first necessary reforms discussed by the Majlis was banking. It consisted in the creation of a national bank to solve the problem of an acute shortage of capital in the country. The deputies feared foreign interference and believed that Iran's external debts could become a pretext for intervention by the colonial powers. Raising funds for the national bank became the task around which the Iranians formed their first anjumans and associations. Women spent their dowries and inheritances and sold jewelry to raise money to establish the first independent national bank. For many of them, these donations were the only capital they really owned. These actions were praised in the newspapers. Wealthy men who continued to keep their savings in European banks were condemned there.

Constitutionalists attached particular importance to the education of girls. On this, their male allies agreed with them – they argued that for the development of the entire nation, educated and self-sufficient mothers were needed who could raise a new generation of citizens. Prior to the constitutional period, the only schools for girls were opened by Christian missionaries from the United States. The Iranian government prohibited Muslim women from attending these schools. The 1907 constitution approved the Iranians' right to general education, but the first general education schools appeared only by 1918. And even despite the serious religious component in their studies, they were constantly criticized and attacked by religious authorities.

The most dramatic event of the Constitutional Revolution was women's response to Russia's ultimatum. The Russian Empire promised to invade Iran if the authorities did not comply with Russian conditions. Russia took advantage of the constitutional crisis in order to increase its influence in the country through the support of the monarchy. To discredit the Majlis, the Russian Empire made demands that violated Iran's sovereignty. In response to gross interference and threats, women's movements organized a demonstration in Tehran on December 1, 1911. Several thousand women participated in this protest. Many took to the podium, made speeches in defense of the revolution and demanded that the Majlis resist the ultimatum of foreign powers. International observers later wrote about this demonstration:

“Out of the walled courtyards and harems, about three hundred women came out with a blush of inextinguishable determination on their cheeks. They were dressed in their simple black dresses with white veils over their faces. Many carried pistols under their skirts or in the folds of their sleeves. They went to the Majlis and, having gathered there, demanded from the president that he receive and listen to them. Lest the president and his colleagues doubt their intentions, Persian mothers, wives and daughters threateningly drew their revolvers, tore off their veils and announced their decision to kill their own husbands and sons, and then themselves, if the deputies did not fulfill their duty to protect freedom and dignity. Persian people."

Islamic revolution

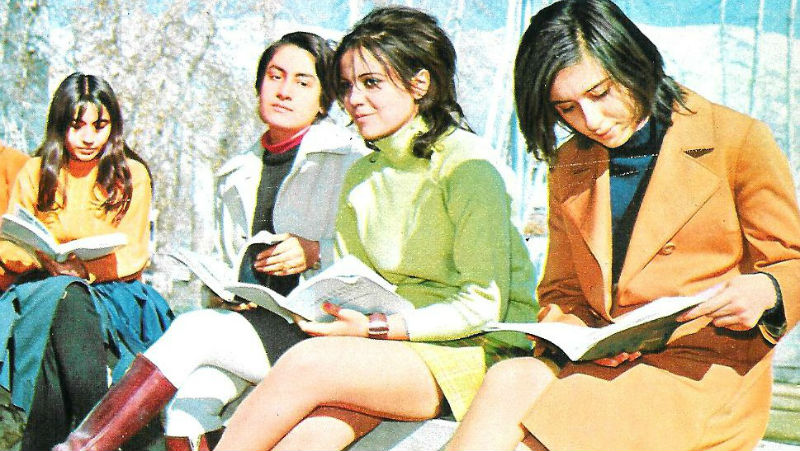

After the independence of the states of the Middle East in the middle of the 20th century, in most of these countries, women found themselves in a difficult position: their political activities had to take place under the auspices of state initiatives and within the framework of what the authorities considered permissible – that is, not be excessively oppositional. The political spectrum of the Middle East and North Africa in the second half of the 20th century can be simply described as a confrontation between Islamists, communists and secular nationalists. But with all the political restrictions, women in the Middle East, thanks to the conquests of the previous generation, received education and opportunities to get acquainted with the ideas of the Western women's rights movement. Iran was no exception here. But a lot changed in 1979.

This may seem surprising to many, but the Islamic Revolution of 1979 involved not only Islamists, but also communists, nationalists, liberals, and even feminists. All of them opposed the authoritarian rule of the Shah dynasty, although, of course, they had radically different ideas about how to organize a new state and political life.

During the protests of that time, women participated in both peaceful and violent mass demonstrations: they dug trenches and fought, joined strikes and boycotts, participated in the activities of self-organized popular militia units, and took part in guerrilla attacks on government facilities. At times, more than a third of the demonstrators were women, and many of them were killed in street clashes. Women donated blood and kept hospitals running, for example by bringing clean bedding. Doctors and nurses worked around the clock, providing medical care to the wounded, lying in hospitals and hiding in their homes. The women hid demonstrators in their homes, and also gathered there with friends and relatives during the curfew to plan their activities for the next day.

On March 8, 1979, tens of thousands of women gathered in front of government buildings and even seized the Palace of Justice, protesting against the already obvious intentions of Ayatollah Khomeini to introduce the mandatory wearing of the hijab. One of their slogans that day was "We will not let the revolution turn back."

In 1979, as many times before, the elites who came to power, including with the help of women, did not fulfill their promises and not only did not make the country more equal in rights, but also deprived women of many of the achievements of previous revolutions. However, the great historical experience of women's struggle for their rights has not disappeared without a trace, and recent events clearly demonstrate this.