Germany is looking for a reason

Adolf Hitler, who annexed the Sudetenland in 1938, promised that it would be his "last territorial claim." For a new aggression Germany needed a weighty reason. Throughout the spring and summer of 1939, the Nazi government actively complained about the oppression of the German minority in Poland, while working on an invasion plan. On August 31, a detachment of SS men staged a "Polish" attack on a German radio station in Gleiwitz, located five kilometers from the border. On September 1, Hitler said in an address: “Last night regular Polish troops bombarded our territory for the first time. At 5:45 am our soldiers returned fire.” German troops entered Poland. There was no declaration of war. The German side limited itself to calling its actions "self-defense", "counterattack" and "return fire". The case in Gleiwitz seemed trifling to the world community, but the Germans, already quite inflated by propaganda and the endless broadcast of the atrocities of the Poles in the press, easily considered themselves victims.

The fears of losing the First World War returned to Germany. The streets were empty and ominous. The country fearfully waited for the reaction of Poland's allies. The Germans wanted to solve the Polish question, but few were ready to fight because of this with Britain and France. This is confirmed by survey data from Upper Franconia: “The answer to the question of how to solve the problem of “Danzig and the [Polish] corridor” is the same for most people: inclusion in the Reich? Yes. By military means? No". The fact that the Polish crisis affects the interests of Germany was agreed even by people who were initially not very loyal to the regime. The writer Jochen Klepper, married to a Jewess, wrote in those days:

“The German East is too important for us not to understand what is being decided there now. <…> We cannot wish for the collapse of the Third Reich because of grievances, as many do. It's completely impossible. In the hour of an external threat, we cannot hope for a rebellion or a coup.”

Many thought about the “hour of external threat”. Teacher Wilm Hosenfeld told his son: "All domestic ideological and political differences must recede into the background, and everyone must be German in order to fight for the people." By evening, the alarm had already sounded in Berlin – Polish planes had entered German airspace. The sirens were quickly turned off: nothing threatened the capital that night.

On September 3, in the afternoon, the British government declared war on Germany. France joined in the evening. The German doctor August Töpperwin, who had already gone to the military enlistment office to sign up as a volunteer, and was refused, was choosing words for the audience of his lecture on theology. In the end, he chose the slogan from the brass belt buckles of German soldiers: Gott mit uns – "God is with us." For Germany, the real war began on 3 September. Life in the Reich changed – the drafted soldiers were located in active units, the girls signed up for medical courses, the old men went to bed in alarm. Nobody wanted war. The Germans, however, believed that they did not choose it, that it was imposed on them from outside.

The Germans believed that they did not choose war, that it was imposed on them from outside

Poland thought that Hitler would win back the border lands between West and East Prussia from its neighbors. The German army chose other directions – from the north and south to Warsaw. She bombed cities and columns of refugees, carried out mass executions of prisoners of war. "Terribly embittered at the Poles" the Germans considered the atrocities justified.

The weekly film review Wochenschau "fed" the viewer reports where captured Polish soldiers talked about orders to exterminate the German minority. The government spoke of genocide against the Germans in Poland. In November 1939, the German Foreign Ministry published a book with photographs of the atrocities of the Poles – dismembered women, wagons loaded with the dead, mutilated children's faces. In a speech in Danzig on 19 September 1939, Hitler referred to "tens of thousands" of "our German brothers" who were "chased away, tortured or executed in the most cruel manner". He said that "sadistic maniacs succumbed to their perverted instincts, and the pious democratic world looked on calmly." And further, for contrast: "I gave the order to German aviation to conduct this war humanely – to attack only combat units."

By October 6, Germany had completed its occupation of Poland. Speaking in the Reichstag, Hitler repeated that he had no territorial claims against France and Britain and offered them peace. The Germans again had hope for the restoration of pre-war peace. Newspapers were full of headlines: "Germany's desire is only peace", "Cooperation with all the peoples of Europe." When rumors reached the capital on Monday 9 October that the British government had agreed to negotiations, thousands of people took to the streets to celebrate the news. To stop the uncontrollable enthusiasm, the authorities issued an official denial. Britain and France did not accept peace. A period began, which would later be called the "strange war" – the countries at war practically did not conduct hostilities.

Formation of the cult of sacrifice around the Germans

Until 1939, Hitler's method at home and abroad was to talk about peace in preparation for war. During the Munich crisis of 1938, when the fear of the German public before the war became especially obvious, the chancellor realized that the people did not share his aggressiveness. The Nazi government could not openly strive for war and was forced to hide behind peaceful slogans and initiatives. It was not until November 1939 that the German press was ordered to stop "peace propaganda" and present events in such a way that "the inner voice of the people themselves gradually began to call for the use of force."

The Hitlerite dictatorship carried out acts of aggression in such a way that most of the country's inhabitants did not notice them. Violence remained abstract and very distant for them: they punish Jews, homosexuals, enemies – not us. The Germans felt tangible restrictions only when a ban was issued on listening to enemy radio broadcasts. Receivers sold in shops were labeled with a special sticker reminding them that listening to foreign radio was a crime against national security. The Germans, however, continued to turn to the media of other states – albeit with some caution. For example, they lowered the volume, switched to German radio stations after the session, or simply made sure that none of the neighbors could hear enemy speech. However, some Germans found the restrictions offensive: the people of the Reich did not understand how listening to foreign radio broadcasts could undermine their personal faith in the Fuhrer and the government.

Many people in the Reich did not understand how listening to foreign radios could undermine their personal faith in the Fuhrer and the government.

German radio conducted active counter-propaganda. It regularly ridiculed statements by British and French broadcasters, accused them of lies and manipulation, nicknamed Churchill "Lord Liar" and called him WC. Information about torture in concentration camps, of course, was carefully concealed. Nazi propaganda formed a cult of sacrifice around ethnic Germans – it assured that everything German in the world was banned, restricted, and tortured. The Third Reich itself, in contrast, acted as the guardian of European values. When German cities began to be bombed, Goebbels in the press paid more attention to the pedantic enumeration of architectural losses than to human casualties. Until 1945, Shakespeare was demonstratively staged on the Berlin stages.

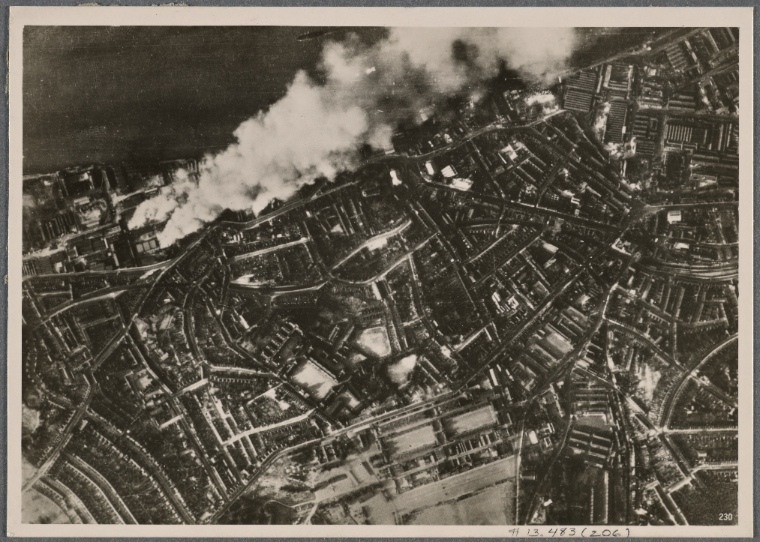

On May 10, 1940, at 11:00 a.m., the press received reports from the German Propaganda Ministry: “Holland and Belgium have become new targets of attack by the Western powers. English and French troops entered Holland and Belgium. We strike back." Nothing has changed in the cities, but people again waited for the bombings, queuing in front of the stalls to buy fresh newspapers. On this day, about sixty bombs fell on German Freiburg. Germany blamed "Allied aircraft" for the attack. The war has entered a new stage, everything has changed on the Western Front. The German authorities threatened:

"From now on, every bombing raid by the enemy against the civilian population in Germany will meet with a fivefold response of German aviation against British and French cities."

The next day, the Germans were told that thirteen children had been among the victims in Freiburg. Killing them will be a pretext for manipulation for years to come. Information that the bombing of Freiburg was erroneously carried out by the German air force (Luftwaffe) will only appear after the war.

Residents of Germany did not turn off their radios even at night. Military experts from the Ministry of Propaganda commented on the events from everywhere: they reported on air supremacy, on the colossal pace of the advance of troops. Soldier Ernst Hooking from the front wrote:

“And to the question “where next?” we answer: “To Paris”, “To Monsieur Daladier”.

On June 22, France laid down its arms. The Germans took to the streets to celebrate and triumph. Since the 1920s, when they seemed resigned to decline and decay, they had been taught to see France as a "hereditary enemy" and now it was finally defeated. To motivate the soldiers, military leader Hermann Goering ordered the post office to accept any number of parcels for shipment home. The number of parcels sent to the rear from France has increased fivefold. Soldiers were also allowed to bring home whatever they could carry, so that the Paris train stations were bursting under the weight of the loot. And yet, even in this euphoric frenzy, most Germans, to Hitler's displeasure, continued to desire peace.

Hitler saves Britain from her own government

On July 19, 1949, at the Kroll Opera, the Fuhrer was again forced to pretend to be a peacemaker. He repeated that he saw no reason why the war should continue. Three days later, the BBC broadcast Britain's rejection of the peace initiative. On August 1, the Luftwaffe received a directive to launch attacks. Berlin aviation, which had time to prepare new bases on the continent, began to bomb English cities. British planes flew in response to Germany. The Germans, who had been promised a secure rear, were nervous. Hitler used this to justify an even more active deployment of the campaign. In his speeches, he repeatedly promised to "wipe" the cities of enemies from the face of the earth. English reporter William Shearer recorded a conversation with his cleaning lady: "Why are they doing this?" she asked him, referring to the British raids. "Because you're bombing London," Shearer replied. "Yes, but we are bombing military installations, and in the meantime the British are bombing our homes." “Maybe,” Shearer suggested, “you bomb their houses, too?” “Our papers say no.” The German press stressed that the Reich was waging an "honest and chivalrous war" limited only to "military objectives".

German Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels found it difficult to correct the Anglophile views of his people, so he decided to separate the British from their government. The Germans were bombarded with articles, films, programs and books about unemployment in England, social inequality and the hard life of the common man. German propaganda claimed to be saving the British from "plutocracy". The Münster journalist Paulheinz Wanzen noted: "Our political aims are to distinguish between the people and the government." When, after the first months of the bombing, it became clear that the people in England were not going to take advantage of the opportunity to overthrow the government, the Germans began to doubt. They said to each other: "The people in Britain certainly don't feel languishing under the shadow of a plutocratic regime."

Both sides counted losses and kept records of downed aircraft – and both, of course, lied. By mid-September, after another radio conversation with Air Force General Erich Quade, some who recorded the reports began to notice: “If England had as many aircraft at the beginning of the war as Quade said, then, minus all those shot down, she should not have a single , unless the British aircraft industry performs indescribable miracles. In May 1941, Goering assured the camp that the British armaments industry had suffered "tremendous damage to the point of complete destruction." On May 10, the Luftwaffe carried out its last major attack on London. The combat strength of their bombers was reduced to 70% in relation to May 1940. Endless bombardments, each of which was called in the press "worst", "longest", "most powerful" and so on, did not yield anything. Journalist Paulheinz Wanzen noted: “In general, people are aware that the war will be long, but they are not especially worried or worried about this. In the current phase, the war is almost invisible.

Apathy among the German people

The Germans heard rumors about troops in the east, but the war that broke out in 1941 on the second front still came as a surprise to many. The failure of the campaign against Britain forced Hitler to turn around. The raids on England did not bring results, and the Reich command considered that the elimination of a potential ally would force the British to sit down more willingly at the negotiating table. At dawn on June 22, immediately after the invasion of the territory of the USSR, Hitler's speech was read in the troops. In the morning, Goebbels repeated it over the radio:

“Moscow treacherously violated the conditions that were the subject of our friendship pact. <…> While until now circumstances forced me to remain silent, now the moment has come when the wait-and-see policy is not only a sin, but also a crime that violates the interests of the German people, and consequently, of the whole of Europe.

Since the non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union was in place until June 22, there was no propaganda against the new enemy in the country, so the Third Reich played the old card – preemptive strike, violation of the border, "Russian patrols penetrated" … Russians began to be represented in the press "barbarians" and "savages". On July 8, the newspaper Völkischer Beobachter wrote: "The German soldier is returning human rights to where Moscow tried to drown them in blood." Hitler again exposed himself and his people as a victim, forced to endure, so that later, at a decisive moment, to stand up for Europe. The Germans Viktor and Eva Klemperer recalled that in a cafe in the center of Dresden, a woman handed them a newspaper with the words: “Our Fuhrer! He had to endure all this alone so as not to disturb his people!”

At first, this campaign met with the approval of the Germans. However, it dragged on catastrophically. The Third Reich could not win a war of attrition against the Soviet Union. When, in November 1941, the Reich Minister for Armaments and Ammunition, Fritz Todt, was preparing to report to Hitler, he wrote to himself that "this war can no longer be won by military means." Then Hitler asked: "Well, how can I finish it?" Todt replied: "In a political way." In February 1942, Todt died in a plane crash. In January 1942, Goebbels had already noted "the general defeatism in government circles in Berlin." Some of the establishment (such as Ernst Udet, one of the leaders of the Luftwaffe in charge of procurement, and industrial magnate Walter Borbet) shot themselves, others showed heart problems. The circle of the Fuhrer's supporters was rapidly thinning out. The population of Germany has ceased to trust the press.

News of the military defeat quickly reached the rear. The civilians stopped reading the news from official sources, increasingly exchanging rumors. Soldiers from the front wrote about shortages of supplies, lack of winter clothes and food. The official "Instructions to the personnel of the troops", received at the front in March 1942, forbade them to express dissatisfaction: "Anyone who complains and makes accusations is not a real soldier." Randomly checked mail. Goebbels forbade the media to write about the hardships of the army. Hitler began to address the nation on the radio more frequently. His figure still evoked the greatest confidence, so the Fuhrer urged to believe him again and spoke of upholding freedom not only for himself and his children, but for all of Europe. On December 20, 1941, Goebbels proposed by radio to start collecting winter clothes for soldiers "as a Christmas present from the German people to the Eastern Front." The need to collect clothes in the rear for, as the press had recently assured, a well-equipped army, caused apathy among the Germans. In the Reich, chronic food shortages turned into famine.

Goebbels' propaganda miscalculation

In January 1943, the ideal Goebbels propaganda gave a noticeable failure. On January 30, on the tenth anniversary of the regime, Hermann Goering delivered a speech about the feat of the 6th Army at Stalingrad. He compared those fighting there with the Spartans of King Leonidas, who defended Thermopylae:

«Даже и через тысячу лет каждый немец будет говорить об этой битве с религиозным благоговением и почтением и знать: несмотря ни на что, там решалась победа Германии».

3 февраля немецкое радио объявило об окончательном завершении битвы:

«Жертва 6-й армии не была напрасной. Послужив бруствером в исторической европейской миссии, она на протяжении нескольких недель сдерживала натиск шести советских армий… Генералы, офицеры, унтер-офицеры и солдаты сражались плечом к плечу до последнего патрона. Они погибли, чтобы жила Германия».

Правительство объявило трехдневный траур. Однако срежиссированная Геббельсом сталинградская трагедия вызвала в обществе истерику. Народ, до этого не мысливший категориями поражения, вдруг столкнулся с поражением неслыханных масштабов. Эмоционально немцы оказались к такому не готовы, тем более что Гитлер всего пару месяцев назад заверял всех в скорой победе под Сталинградом. Никогда прежде ложь фюрера не казалась такой очевидной: «Гитлер врал нам целых три месяца», — сетовали немцы. Катастрофическая военная недееспособность Германии перевернула настроения в обществе. Фюрер срочно велел забыть о Сталинграде — словно бы никакой битвы не было. О ней не писали, ее не комментировали, с ней не проводили параллели. В 1944 году первая годовщина сражения прошла в полном молчании. Геббельс лишь отмахнулся в прессе: «Совершать иногда ошибки есть суверенное право руководства». Но нация, так остро боявшаяся поражений, уже поняла, что проигрывает.

Катастрофическая военная недееспособность Германии перевернула настроения в обществе

За пять лет войны Германия устала. Мюнстерский журналист Паульхайнц Ванцен записал анекдот:

«В 1999 г. два бойца мотопехоты на Кубани сидят на предмостном плацдарме и болтают от нечего делать. Один из них вычитал в книге слово “мир” и хотел узнать его значение. Никто в землянке не знал его, и тогда решили спросить фельдфебеля. Оказалось, что и он не знает, а потому обратились к лейтенанту и командиру роты. “Мир? — переспросил он с сомнением, качая головой. — Мир? Вообще-то я ходил в гимназию, но такого слова не знаю”. На следующий день ротный очутился в батальонном штабе и там спросил своего командира. И он тоже не знал, но у него нашелся недавно опубликованный словарь, в котором он и вычитал: “Мир — непригодный для людей способ жизни, упразднен в 1939 г.”».

Западные области Германии скоро подверглись массированным атакам. Жители попавших «под раздачу» регионов негодовали. В Рурском бассейне популярность получила издевательская частушка, намекающая на речь Геббельса во Дворце спорта с вопросом «Хотите ли вы тотальной войны?»:

«Милый томми, цель вдали. / Шахтеры мы — не при делах. / Лети себе дальше — на Берлин, / Ведь там орали: «Да! Да! Да!»

Геббельс обещал возмездие за каждый из ударов — но возмездие задерживалось. Жители прятались в подвалах, голодали, засыпали от усталости по дороге на работу. Швейцарский консул Франц Рудольф фон Вайс так описывал настроения в Германии: «Глубокая апатия, поголовное безразличие и желание мира».

«Самый черный день» или долгожданный мир

Вечером 20 июля 1944 года Третий рейх узнал о покушении на Гитлера. После полуночи по радио выступил он сам. Голос у него был чуть более напряженным, чем обычно:

«Мои немецкие товарищи! Я выступаю перед вами сегодня, во-первых, чтобы вы могли услышать мой голос и убедиться, что я жив и здоров, и, во-вторых, чтобы вы могли узнать о преступлении, беспрецедентном в истории Германии. <…> Совсем незначительная группа честолюбивых, безответственных и в то же время жестоких и глупых офицеров состряпала заговор, чтобы уничтожить меня и вместе со мной штаб Верховного главнокомандования вермахта».

Несмотря на царившую в обществе апатию и на понимание тупикового положения Германии, на случившееся уже осознание многолетней лжи, покушение вызвало резкое, бескомпромиссное осуждение.

Отец командира танкового подразделения Петера Штёльтена в письме к сыну писал: «Как могут они ставить в такую опасность фронт?» Даже критически настроенные к нацистам граждане пребывали в убеждении, будто «только фюрер способен управлять ситуацией и что его смерть привела бы к хаосу и гражданской войне». На улицах едва не плакали: «Боже, спасибо, что фюрер жив». Министерство пропаганды устраивало митинги в честь «ниспосланного Провидением спасения» Гитлера.

Парадоксально, но общество требовало еще большей мобилизации. Немцы были уверены, что по-настоящему Германия еще ничего не начинала, хотя к осени 1944 года страна ушла в глухую оборону. В августе предводитель гитлерюгенда Артур Аксман призвал добровольно вступать в ряды вермахта юношей 1928 года рождения — им исполнилось 16 лет. В течение следующих шести недель 70% этой возрастной группы подали заявления о зачислении в солдаты. Однако для прибывающих бойцов у правительства уже не нашлось ни оружия, ни обмундирования.

Пытаясь спасти ситуацию, Геббельс придумал новый лозунг: «Время против пространства». С его помощью министр пропаганды пытался заверить население, что потери и постоянное отступление армии в 1943 и 1944 годах дали рейху время для создания нового таинственного оружия, которое скоро будет применяться на фронте и переломит ход войны. 30 августа Völkischer Beobachter опубликовала статью военного корреспондента Иоахима Фернау «Тайна последней стадии войны»: в ней журналист рассказывал об оружии неслыханной мощи. Многие из немцев готовы были слепо верить этим заверениям, потому что больше верить было не во что.

Новости о лагерях смерти, в которых массово убивали с помощью газа или тока, продолжали распространяться по территории страны, парализуя нацию. Половину Берлина разрушила вражеская авиация. Гитлер «пропал с радаров». Он так редко обращался к публике, что после его новогодней речи 1944 года люди делились, как рады «слышать вновь голос фюрера». Для многих, правда, он звучал «глухо, точно из могилы». У Гитлера действительно вряд ли мог бы найтись повод для радости. Скромные остатки его «Великого германского рейха» умещались между Одером и Рейном. До развязки оставалась пара месяцев. В канун Рождества, обсуждая подарки, немцы шутили: «Будь практичным — подари по гробу», а аббревиатуру LSR (Luftschutzraum, «бомбоубежище») расшифровывали как Lernt schnell Russisch («учи быстрее русский»).

9 мая 1945 года мир, которого так страстно желали немцы, наступил. Он оказался не таким, как ожидалось, — страна встретила поражение тихо, без особенного сопротивления. 16-летний Вильгельм Кёрнер записал в дневнике: «9 мая, безусловно, войдет в немецкую историю как самый черный день. Капитуляция!» Но большей части было уже всё равно, кто выиграл, а кто проиграл, даже если проигравшими оказались они сами.

Бессмысленные потери

Еще в феврале 1943 года Геббельс, планируя создание сталинградского мифа, поручил пропагандисту 6-й армии Хайнцу Шрётеру сделать подборку из писем сражавшихся под Сталинградом немецких солдат. Геббельс думал, что немцы, читая их, будут мечтать о возмездии.

После войны эти письма опубликовали и перевели на множество языков. Их сделали частью обязательного чтения в японских школах. Их много раз перечитывали и в самой Германии. В письмах домой солдаты обращались к близким: «Здесь настоящий ад. Пикирующие бомбардировщики и артиллерия»; «Из головы не выходит мысль, что твой конец близок. Наши атаки безуспешны»; «Дорогие мои родители, если возможно, пришлите мне еды. Я это пишу так нехотя, но голод велик. Мы, оставшиеся в живых, едва можем ходить»; «Пожалуйста, не волнуйтесь после того, как прочитаете эти строки. Мы здесь в безнадежной ситуации. Я приветствую и прощаюсь с вами, дорогие, потому что, когда это письмо дойдет до вас, моя жизнь уже закончится».

Не подкрепленные геббельсовской пропагандой, письма стали именно тем, чем были — демонстрацией бессмысленности и жестокости войны, глухим и отчаянным желанием мира. В катастрофе под Сталинградом отразилась катастрофа всей Германии — обманутую, голодную, измученную нацию тоже бросили умирать на чужой войне.

В тексте использованы материалы книги Николаса Старгардта «Мобилизованная нация».