In 2014, a street art museum appeared in St. Petersburg. It opened with the anti-war exhibition Casus Pasis (“A reason for peace” – Latin), in which 30 Russian and 27 Ukrainian artists participated. The director of the museum, Tatiana Pinchuk, recalls that initially an exposition dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the First World War was being prepared for the opening. However, after the events in the Crimea and Donbass, the exhibition was urgently remade to fit the Ukrainian agenda.

Even before the opening, the museum received a phone call from someone who introduced himself as Aleksey, in his own words, a “curator” from the FSB. He said that at that time he had under his supervision three institutions working with contemporary art < modern art, approx. The Insider> : the Museum of Street Art, the Department of Contemporary Art of the Hermitage and the Museum of Contemporary Art Erarta.

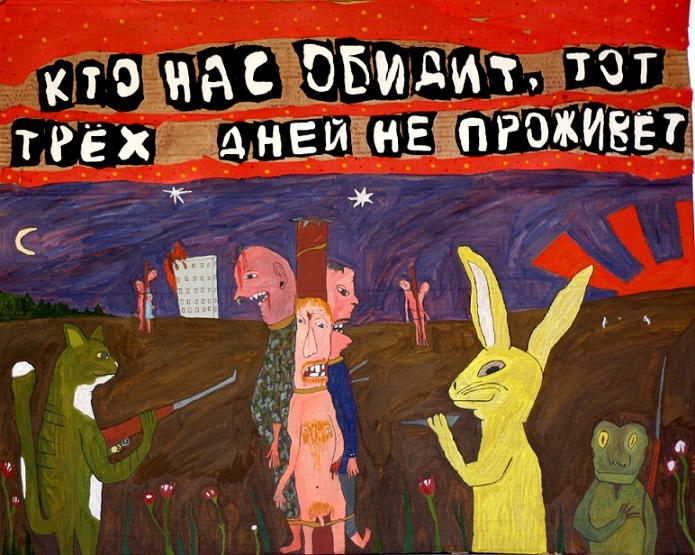

Aleksey walked around the exhibition that was not yet open and asked to remove some of the works, among which were the works of Pasmur Rachuiko and Grigory Yushchenko.

When Tatyana asked Alexei whether this was a prescription or a recommendation, the “special art critic agent” said that if his advice was not taken into account, the museum could start to have problems.

The exposure did not change. The Casus Pasis exhibition was a success. The museum began to work, but Tatyana recalls that it was quickly deprived of access to state grants and constantly staged excessive fire safety checks.

Aleksey continued his vigilant oversight for eight years and watched almost all the exhibitions until the museum closed after the start of a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In 2023, such “curators in uniform”, people who check the compliance of exhibitions with the state agenda, is a common practice in Russian cultural institutions. True, now, if the "curators" do not like something, the exhibition can be closed, and a criminal case can be opened against the organizers or artists.

We have a cancellation!

Over the past year alone, the Moscow Museum of Modern Art has canceled the exhibition "Thin Citizens", the Tretyakov Gallery has curtailed the already open exhibition "Change of Scenery" by Grisha Bruskin, the exhibition "Maps of Meaning" by Pavel Brat has not taken place in Voronezh, the state gallery "On Kashirka" decided not to show earlier the planned exhibition “Signboard-Message”, which was moved to the Zverev Center for Contemporary Art, the pro-Kremlin movement SERB achieved the closure of the exhibition “Autonomous Zone” in Open Space, after checking the “black lists”, the list of participants in the “Thinking Landscape” exhibition at the Museum of Moscow was radically reduced by Oleg Kulik opened a criminal case on the rehabilitation of Nazism for the sculpture "Big Mother"… and this is just the tip of the iceberg.

Artist Pavel Otdelnov, winner of the Innovation Award, told The Insider that he, apparently, was also blacklisted.

In November 2022, Pavel received a call from a well-known state museum and was told that, contrary to agreements and plans, his work was being removed from the exhibition. The General Affairs Officer insisted on this.

Pavel is sure that the point is not even in the content of the work, but in his views: “The work is absolutely neutral. [All that happened] only because I express an anti-war position, and maybe also because I am now outside of Russia, which is now considered as a betrayal.”

Another incident occurred earlier in the same 2022 with the exhibition “Exit Through the Red Door” at the Tretyakov Gallery, in which, among others, Otdelnov’s work “Landscape with Reflection” participated. After the revision of the “curators in uniform”, the exhibition was postponed several times, and eventually took place, but under a different name and without even being mentioned on the museum’s website.

Alexandra Selivanova, former director of the Avant-Garde Center, confirms: according to her information, at least in the Tretyakov Gallery and the Pushkin Museum im. Pushkin has been working with special deputies since the summer, making sure that all the exhibited works comply with the National Security Strategy of the country.

In the summer, the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation ordered federal institutions to closely monitor the content and suppress any manifestation of free thought. Curators must monitor artists' social media, and creators wishing to showcase their work in publicly funded museums are now required to submit CVs stating their travels abroad over the past few years.

The situation in which Russian culture finds itself after the start of the war is not only deplorable, it is absurd. The exhibition can be closed for lack or excess of patriotism. In November 2022, the Tretyakov Gallery decided not to open the Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art the day before the start.

Moreover, the list of participants made it possible to call the exposition moderately “patriotic”. The authors for the Biennale were selected by a council headed by a well-known patriot, General Director of the Hermitage, Mikhail Piotrovsky. Sergey “Afrika” Bugaev made a project for the exhibition on the demolition of “Russian” monuments in Europe, and Anastasia Deineka planned to show portraits of people from Donetsk occupied by Russia back in 2014.

“Contemporary art is usually considered marginal, we are suspected in advance, in advance, of hooliganism and nihilism, we are always seen as a “fig in your pocket”. And we didn't have it. In March 2022, we decided that we were working for our viewers, now we are all going through, perhaps the most difficult test for our country and in the life of each of us. And you should at least try to pass it with dignity. We tried,” the organizers justified themselves before the censors.

However, later KP wrote that the exhibition, they say, was canceled due to the position of the Tretyakov Gallery, which did not want to exhibit too “patriotic” works by artists from the “LPR” and “DPR”. While this material was being prepared, the long-term director of the Tretyakov Gallery, Zelfira Tregulova, resigned from her post, and will be replaced not by an art critic, but by a confident personnel officer and hereditary bureaucrat Elena Pronicheva, the daughter of Vladimir Pronichev, the former head of the Russian Border Service and deputy director of the FSB.

From a social institution to an institution of power

There has always been censorship in art. In princely and tsarist Russia, these functions were taken over by the church. Alexander Pushkin, as we remember from the school literature course, sent his works for qualification at the same time to Tsar Nicholas I, who declared himself the "personal censor" of the poet, and to the civilian censor.

In the USSR, when the borders were closed, censorship for people of creative professions was simply inevitable. Entire generations were brought up in the paradigm that there can be no alternative to censorship in principle, it has firmly entered everyday life, and only desperate daredevils and outcasts tried to openly oppose it.

After the collapse of the Union, in the turbulent time of the formation of the new Russia, a short period of freedom began. The state was so focused on the redistribution of spheres of influence, solving strategic business problems, consolidating the bureaucratic apparatus, that, by and large, no one cared about artists and artists.

In modern Russia, censorship began to manifest itself institutionally around 2004. In preparation for the first Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art, the organizers and participants were told that they could show whatever they wanted, but there were three taboo topics: the church, Putin, and Chechnya.

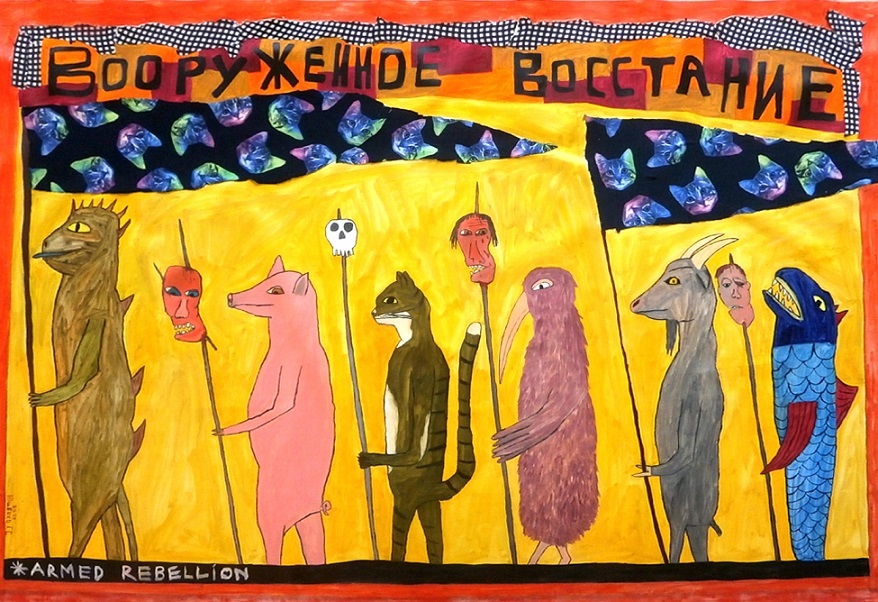

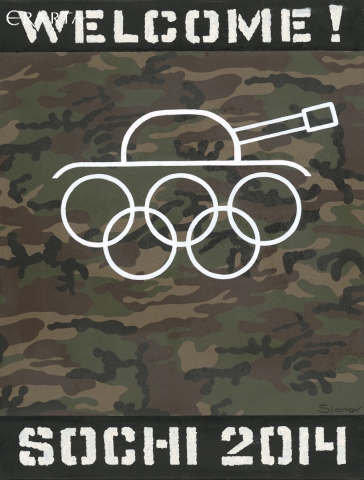

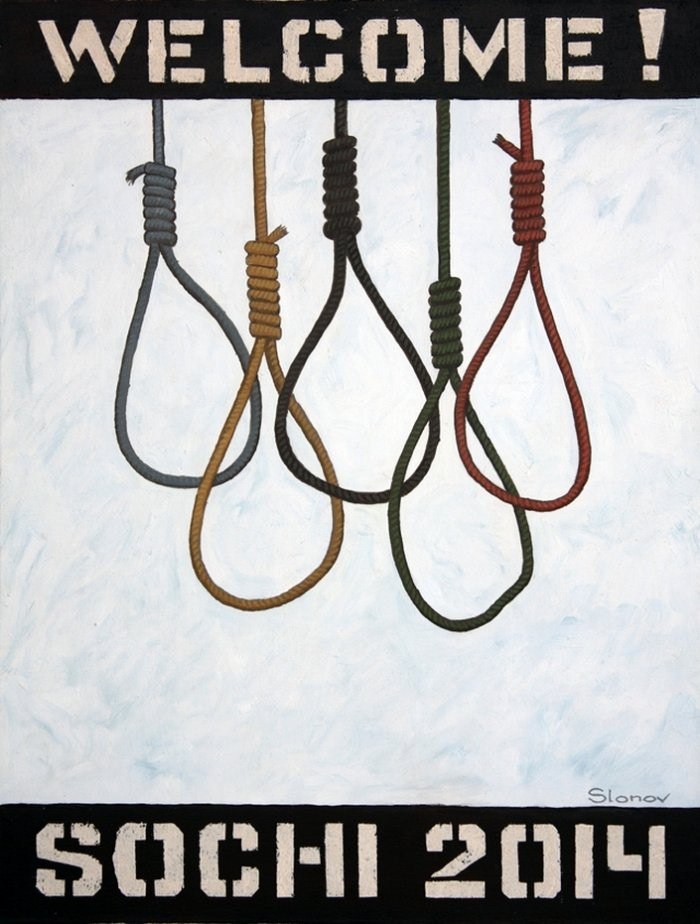

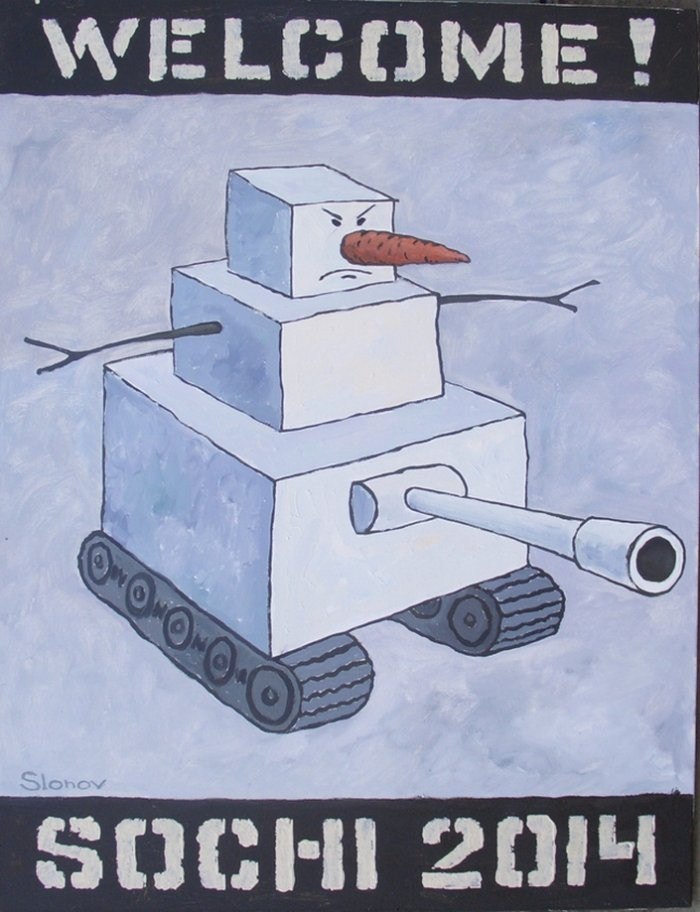

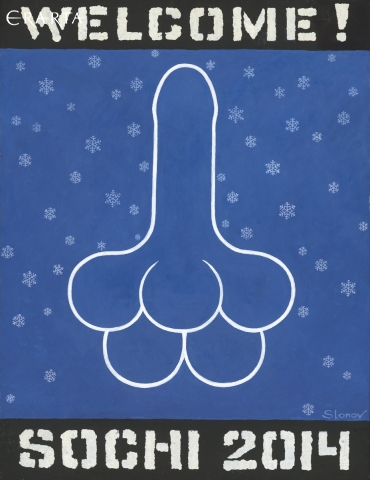

In 2014, Marat Gelman, then director of the Perm State Museum of Modern Art, prepared Vasily Slonov's exhibition "Welcome to Sochi". A series of works touched upon a sensitive story with the personal PR of the president and sports washing, which the Sochi Olympics were.

The work of Vasily Slonov was not liked by the censors. “It turned out that Sochi is also a taboo topic. But no one warned,” Marat Gelman told The Insider.

After the events in the Crimea and Donbass, the cultural isolation of Russia from the global art market began. It was a kind of cultural sanctions. Russian artists were less likely to be invited to participate in international exhibitions, gallery owners were deprived of representation at foreign art fairs, and the demand for Russian contemporary art fell everywhere.

Vyacheslav Surkov is considered an evangelist of the cultural policy of Russia at that time. His demand was simple: "You can do whatever you want, but you must be loyal to the government and its agenda."

The professional art community in Russia as a whole has accepted the rules of the game, and “sick” topics have not been raised in institutions affiliated with the state in one way or another.

The brainchild of oligarch Roman Abramovich, the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art brought exhibitions by Yayoi Kusama, Urs Fischer, Takashi Murakami and Louis Bourgeois to Moscow. Indeed, when the viewer has the opportunity to see the works of such classics, he does not ask himself: “Why don't you show Pyotr Pavlensky or Pussy Riot?” He simply says: “Thank you.”

But the price to pay to reproduce this illusion of normality was silence.

Reasonable Conformity Theory

While Russian intellectuals believed in the theory of good deeds, the departments formed "black lists" of objectionable artists and forbidden topics that the institutions carefully avoided. State and large private funds were allocated to those art projects that did not touch on sensitive topics. "Neutrality" and apoliticality have become the norm.

The story that happened with the Innovation Prize in 2015 is indicative. The absolute favorite of the award was Pyotr Pavlensky and his action "Threat". But the organizing committee of the award at the last moment withdrew the artist's work from the competition without explanation and without discussion. However, this did not cause a scandal in the art community: only four of its members decided to leave the expert council of the award – Ilya Dolgov, Anna Tolstova, Dmitry Ozerkov and Sergey Khachaturov. And in the end, the award in the nomination "Work of visual art" was simply not awarded.

The lack of community response to high-profile events increased the habituation to conformism. The lion's share of the art market in Russia has been opportunistic and loyal to the state for years.

This led to the fact that even after February 24, few Russian cultural institutions staged a demarche.

On the contrary, after the announced sanctions, Russian art figures had a final understanding that they had lost access to the world market. And the state quickly prepared cultural import substitution: as compensation for international isolation and loss, the artists were offered the domestic fair “1703” in St. Petersburg , which Tatiana Pinchuk calls “a fair of shame.” According to rumors, buyers – top managers of Gazprom – have invested heavily in Russian art, and sellers – Russian gallery owners and artists – have made good money. Only a few galleries refused to participate in the fair, among them St. Petersburg's Myth and Moscow's Fragment.

Among artists, few found the strength to openly oppose the established system. After all, once on the “black list”, the artist was actually deprived of the opportunity to exhibit at commercial venues within the country, as well as at international forums and fairs, to which one or another Russian gallery could bring him. Many artists have learned to be careful. And then they got used to it. Therefore, when the war broke out, not everyone who was against it publicly stated it directly or even allegorically.

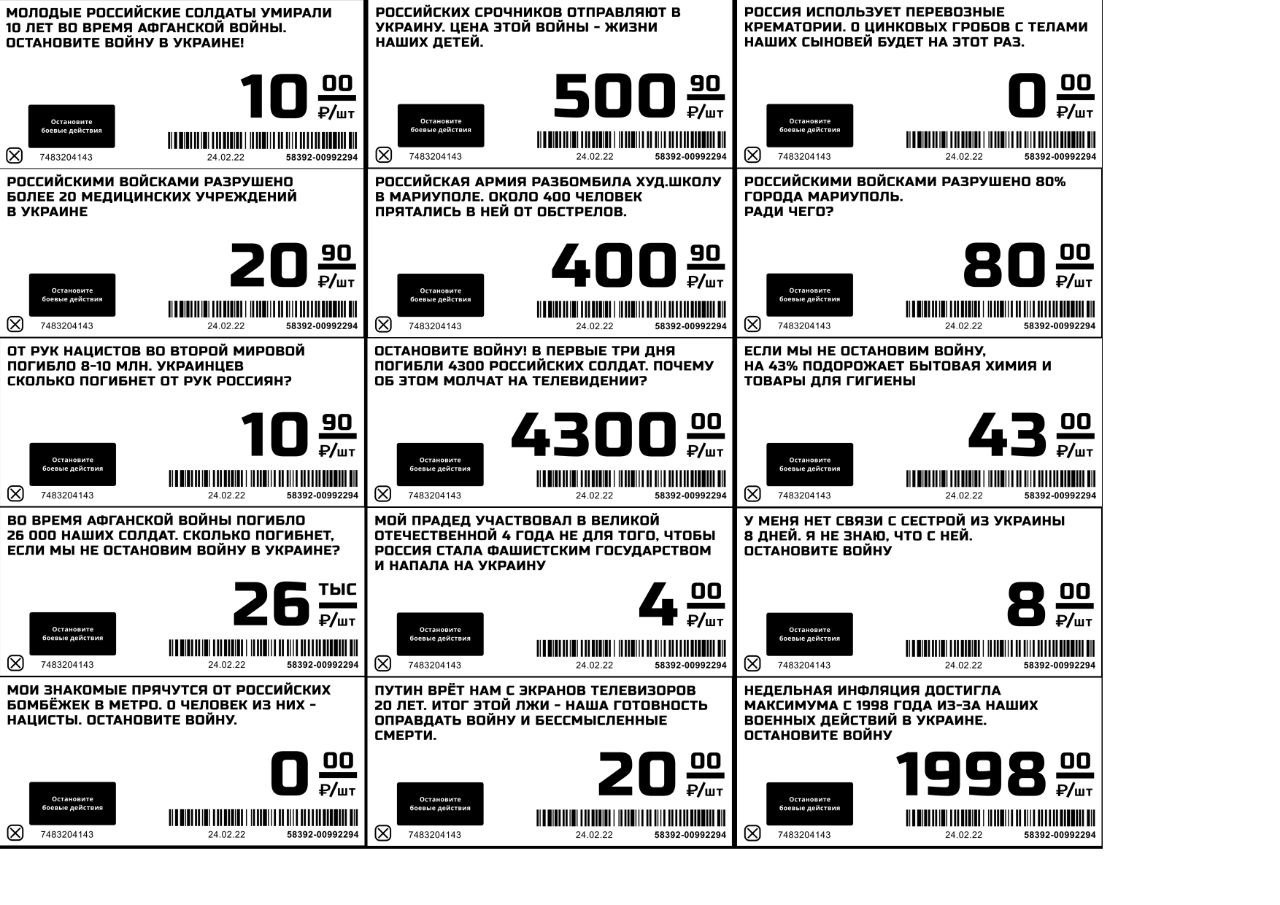

The reaction to the war in the art community was beginning to look promising. More than 18,000 cultural figures have signed an anti-war letter against Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

- Linor Goralik launched ROAR, an online bulletin of oppositional Russian-speaking culture, where authors send their anti-war works.

- Free culture forum SlovoNovo , founded by Marat Gelman, quickly reformatted into an anti-war one.

- A number of Russian musicians strongly condemned the war. Noize MC and Oxxximiron collected money at concerts in support of Ukrainians.

- Pussy Riot tours around the world and pour urine on Putin's portrait on stage.

- Some masters performed in their own way – Ilya Kabakov, Sergey Bratkov, Sergey Anufriev. Artists who used to be strongly associated with Russia are now asking to be called Ukrainians.

- GES-2 hosted a partisan exhibition of the PNI art group.

- “Settings 2.2”, within the framework of which elements were added to the current exposition of the museum, which both the audience had to look for, and after the prank was revealed (but already successful!), The enraged director of the museum.

- Pavel Otdelnov holds exhibitions of his anti-war works in Sweden and the UK.

- Viktor Melamed has been drawing civilians killed in Ukraine every day since the beginning of the war.

- Moderately anti-war work was done by the graffiti artists Slava ATGM, Kirill KTO, Vladimir Abikh.

Several new media projects have emerged that include collections of anti-war artwork: Feminist Anti-War Resistance , Media Guerrillas , Worst Artists Association , Anti-War Art Active.

But all this is a drop in the ocean. Why do the voices of Russian artists not sound as loud as many expected from them? There are both subjective and objective reasons for this.

The first of these is self-censorship. Many artists in Russia have been doing it for a long time, not without success. If before the start of the war it was mainly due to practical considerations (artists did not want to “fall out of the cage” and lose their livelihood), then after the start of the war, fear was added to this. At the same time, we note that just artists have not yet been prosecuted either for "fakes" or for "discrediting the armed forces." The case of Alexandra Skochilenko stands apart, but what the St. Petersburg artist did is more of an actionism than an artistic statement.

Self-censorship can take you far. Curator of the exhibition Dreams of Milk. Semiotic studies for the film adaptation of the novel “The Mythogenic Love of the Castes””, the famous Moscow artist Pavel Peppershtein, before the opening, himself invited a censor from the organs, who eventually rejected several works. When exhibitors protested, Pepperstein explained that the visit of the censor and his expected sanctions were part of an artistic statement from the new reality that now surrounds us.

Censorship, arrests, black lists — all this, the authorities made it clear to artists that in Russia they can live and work only in agreement with the state. And many have chosen self-censorship and found ways for themselves to stay away from the most pressing social and political issues.

The second reason why some Russian creators are silent is that they are deleted from the context. After the start of the war, the main focus in the art world is now in Ukraine. And this is logical. European gallery owners, who used to work with Russian contemporary art and sold it well, began to actively discover Ukrainian artists, their exhibitions are held everywhere in different cities around the world.

The recent Frieze and Frieze Market fairs in London were held for the first time without the participation of Russians.

Marat Gelman generally claims that there is a "all-Ukrainian lobby" that ensures that Russians are not allowed to participate in large art projects.

This thesis is confirmed, for example, by the story of a collective exhibition in Krakow held in the spring of 2022, one of the participants and headliners of which was the Russian artist Pyotr Pavlensky. Ukrainian artists and activists demanded that the image of Pavlensky's "Shov" action be removed from the exposition of the collective exhibition and from the posters advertising it. As a result, it was possible to defend the work only thanks to the director of the museum, who took a principled position against the infringement of artists on a national basis.

If we talk about artists who are still silent and continue to produce “neutral” art, abstracted from the anti-war agenda, then the dissatisfaction of Ukrainians is understandable. But it seems that this should not concern Russian authors who are public opponents of the war.

However, for example, Pavel Otdelnov, an artist who has repeatedly criticized the war and whose art after February 24 is categorically anti-war, says that he still feels wary when dealing with European institutions.

The problem with legalization in other countries has not gone away either. Well-known artists, who wanted to and decided, have already moved from Russia. But if the majority left, it was not from persecution, but from mobilization: to Kazakhstan, Georgia, Armenia, Turkey. In general, to countries where, on the one hand, a visa is not required and it is inexpensive to live, on the other hand, there is almost no opportunity to continue working as an artist.

Few managed to leave for Europe. Meanwhile, the European Union says it is ready to support the Russians and issue them special visas for artists. Similar Artist Visas are relatively easy to obtain in Germany and France.

Но даже те, кому удалось переехать из России и вроде бы обезопасить себя от «самого гуманного в мире правосудия», все равно опасаются высказываться.

Многие художники все еще подчеркнуто аполитичны. «Пока ты не трогаешь религию и власть, им абсолютно по барабану, кто ты и что ты, — говорит «художник года» по версии ярмарки Cosmoscow Валерий Чтак. — Не хочу никого обидеть, но если ты хочешь заниматься сопротивлением и политикой — это там. А здесь — просто нарисуй хорошую картинку».

Проблема только в том, что вчера государство просило не трогать «запретные темы», сегодня — не выступать против войны, а завтра уже мало будет сохранять нейтралитет. Чтобы оставаться, нужно будет эту войну воспевать.

Марат Гельман называет это «моментом Прилепина»: когда недостаточно быть просто лояльным, нужно уже быть «активно своим». «Дугинско-прилепинская волна», безусловно, накроет всех, кто пытается отсидеться и абстрагироваться, — считает Гельман. — Но будет поздно. В истории их высказывания останутся ровно такими, какими они являются сейчас».

Кажется, что страх настолько сильно поразил российское общество, что и художники — певцы русской природы — отчаянно стараются придумать для самих себя оправдания своего молчания и бездействия.

Цена молчания

Власть добилась своего. Цензура в России, в принципе, больше не нужна. Самоцензура российских художников и деятелей искусства, кажется, не хуже пригожинской кувалды справляется с кремлевскими нарративами.

Нынешняя ситуация развернулась так, что теперь требует от всех героических поступков, рисков, на которые многие художники в силу разных причин решиться не могут. И странно от них этого ждать.

Марат Гельман объясняет это просто: «Художник — не героическая профессия. Все, кто хотел быть героями, пошли в армию, в активизм. Но художник — это и не просто профессия. Это важная общественная роль. От тебя ждут высказывания. И это высказывание — персональное. И если ты не можешь высказаться — просто перестань быть художником».

Несколько художников, с которыми разговаривал The Insider при подготовке этого материала, категорически просили остаться анонимными и не цитировать их.

В исторической перспективе тот факт, что известные российские художники недостаточно активно высказываются о войне в Украине, может негативно сказаться на восприятии потомками реального положения дел. Ведь подавляющее большинство российских творцов войну не поддерживают.

Но страх, рождающий самоцензуру, неуверенность, апатия и прочие причины в итоге приводят к тому, что кажется, что российское художественное сообщество молчит. Что ему нечего сказать. Или, что еще хуже, что оно не хочет ничего говорить. Ведь молчание — это тоже сильное высказывание.