From Deng Xiaoping to Xi Jinping

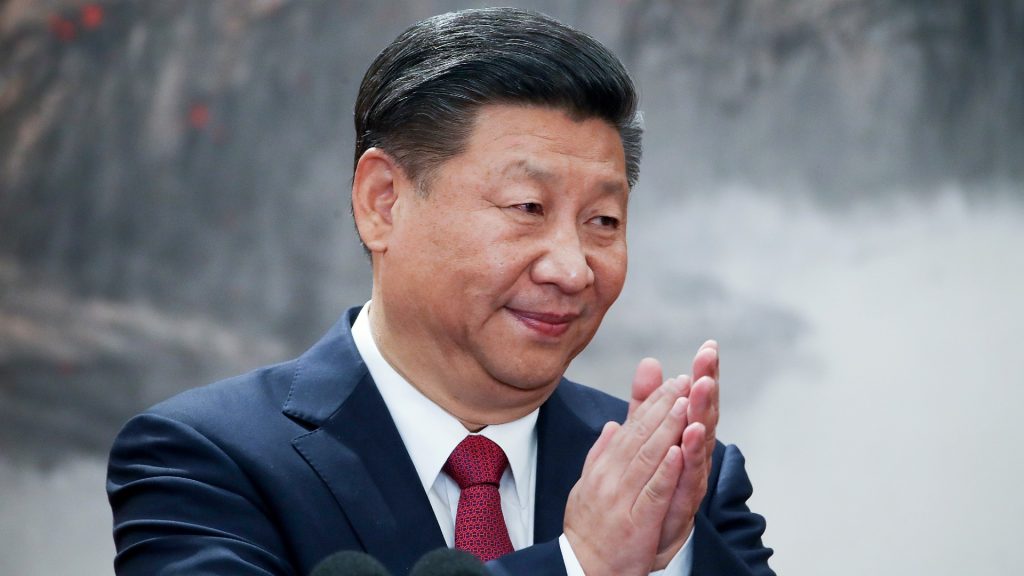

China has never been a democracy, but even despite the one-party system, the elements of pluralism, competition and change of power in the government of the country existed relatively recently. China owes this to Deng Xiaoping, whose “reform and opening up” policy, which began in 1978, included not only the return of a market economy and the transition to foreign policy openness, but also structural changes in the party apparatus, designed to prevent the possibility of autocracy.

Despite the fact that formally the regime remained the same – one-party and authoritarian – the reforms can be called radical. A two-term limitation was introduced into the country's constitution for the President of the People's Republic of China – which, of course, was impossible even to argue before Deng Xiaoping. One-partyism ran counter to the idea of such reform, and to overcome this, Deng began to support, or rather cultivate, the model of "parties within a party"—independent and opposing informal cliques within the CCP. He also laid the foundation for a tradition of active counterweights in the country's leadership positions: after Xiaoping's departure, the general secretaries of the CCP and the premiers of the CPC State Council were appointed by opposing cliques and were forced to work with rivals. This situation created an informal system of checks and balances, fundamentally different from the Western model, where the role of balances is played by institutions, but nonetheless working.

Deng Xiaoping saw the main goal of the reforms as preventing the establishment of autocracy in the PRC.

The traditions and rules established by Deng Xiaoping did not make China democratic, but they effectively ensured the stable functioning of the authoritarian system and successfully prevented the return of totalitarian leaders and autocracy for several decades – until Xi Jinping.

"New Openness" as a new dictatorship

Like Deng Xiaoping, Xi simultaneously pursued reforms in both domestic and foreign policy, albeit in the opposite direction. Since coming to power in 2012, Xi has reversed much of the liberal reforms of the preceding decades. One of Xi's first actions in his new post was to launch a major anti-corruption campaign. Corruption has indeed been and remains a serious problem in China, but as a result of the “anti-corruption campaign”, for some reason, mainly Xi’s political opponents suffered.

Xi quickly built his own group of supporters around himself, refusing to align himself with one of the two mainstream factions within the party. Soon it turned out to be the leading force, and at the moment it is de facto the only unconditionally dominant one: one of the cliques, the Komsomol members, most likely no longer exists, and the second, the Shanghai, has lost almost all influence. As a result, the vast majority of party and state positions are occupied by people loyal to Xi, and there is no political – or ideological – competition left for him in the party.

The vast majority of party and state positions are occupied by loyal Xi people

In parallel with domestic reforms, Xi began a turn away from China's policy of opening up to the world. He consistently built and supported anti-Western sentiments, rejecting "Western values" and "Western liberalism" both at the diplomatic level, openly criticizing the United States, for example, and in the cultural sphere, highlighting and supporting anti-Western ideologists.

"Deliberative democracy" instead of real

The strengthening of autocracy took place gradually and prudently. Despite openly anti-democratic, essentially totalitarian reforms, there was an understanding that democratic elements, or their imitation, were needed to create and maintain the necessary level of popular support. To do this, Xi turned to the concept of deliberative (or consultative) democracy (协商民主). The "consultative" element was an important part of China's authoritarian apparatus before Xi, but now it has been given a special role.

Democratic elements – or their imitation – are needed to create and maintain the necessary level of popular support for Xi

Emphasis on "deliberative democracy" in policy papers and public speeches began in 2013, peaking in 2015 when the Central Committee issued special directives to "strengthen socialist consultative democracy." In practice, this means that citizens have access to a system of petitions and applications, local authorities periodically conduct “consultative polls” regarding political decisions, and also establish “public discussion centers” and other forum formats. Some authors note that in some cases these institutions cease to be imitative and indeed influence decision-making through non-ideal, but generally democratic processes. In short, such processes and institutions should create a democratic vector that could sometimes come into conflict with centralized party control. But in reality, these insignificant facade institutions only strengthen the legitimacy of the Chinese dictatorship, help mobilize political support for Xi and control the local agenda, imitating grassroots initiative.

"Deliberative democracy" in China is provided by a huge, purpose-built bureaucratic machine

Internet and television censorship

As early as 2013, Xi Jinping began to clean up disloyal voices outside the state apparatus. The first and most noticeable measure was the introduction of mass censorship, for starters – on the Internet. The censorship campaign began with the persecution, arrests and public humiliation of popular bloggers who disagree with the authorities. In 2013, as a result of a raid, the popular author of the Sina Weibo microblogging platform, Charles Xue, was arrested on charges of pimping. The arrest followed his appearance on television, where Charles apologized to fellow citizens for "irresponsible posts". The fate of the blogger was repeated by his other colleagues: in the same year, Qin Huoho was arrested for “lawlessness”. At the same time, a campaign began against the businessman, founder of SOHO and part-time one of the largest bloggers in China, Pan Shii. According to some reports, the state put pressure on his company, according to others, he was rumored, publicly humiliated and forced, like Xue, to make a self-deprecating speech on television.

Censorship campaign began with harassment, arrests and public humiliation of popular opposition bloggers

Simultaneously with the persecution of bloggers, the government began to strictly regulate online content. For example, criminal liability was introduced with a restriction of freedom of up to three years for the dissemination of "rumors" – an analogue of Russian "fake news". In the first four months of the censorship campaign, more than one hundred thousand users of Weibo, China's largest network, were removed or restricted by the government.

In 2018, as part of the restructuring of state bodies – mainly with the aim of concentrating control over them in the hands of Xi – the system and institutions of censorship also underwent changes aimed at even stricter control. The three largest TV channels have been reformed into one information network, which, unlike the individual TV channels, is directly under the control of the central propaganda department. This certainly makes it easier to control the content and its compliance with censorship and propaganda norms. Under the leadership of the propaganda department, in addition to the TV channels themselves, the entire cinema industry in China falls, including financing and filming.

Xi's Precepts for Science and Education

Censorship affected both education and science in general. In 2016, Xi Jinping convened a "philosophy and social science symposium" where he delivered a keynote address on the state of science and education in these fields in China. Xi talked about the uniqueness of China and its place in the world, about the role of the social sciences and philosophy involved in finding this place in the first place. The social sciences in China, Xi said, do not provide enough theoretical innovation in the search for Chinese ideology and the construction of socialism, which should be their primary goal. According to Xi, in today's dynamic world, a "confrontation" of ideologies is inevitable, and China's social sciences should prepare it for it. Thus, Xi sees science primarily as a foreign and domestic political tool, at best, a tool of soft power and the spread of Chinese influence. According to the chairman, science in China should be unique, fundamentally different from Western alternatives.

Despite the fact that Xi’s speech can hardly be called very specific and consistent, and even more difficult to build an effective paradigm for the development of science on it, this is exactly what Chinese politicians ultimately tried to do. According to China's Ministry of Education, universities should follow President Xi's guidance. To this end, "Xi Jinping Thought Study Institutes" have been established in most universities. At the same time, academics and teachers are forced to cooperate with censorship bodies that carefully check their work – if they contain "undesirable" elements, the authors can be suspended from teaching and publishing in general, deprived of work and earnings.

Xi expressed the same ideas about art. According to him, Chinese art should express traditional Chinese culture and modern Chinese values. Xi's discourse on art turned out to be even more extensive than on science: for example, in one of his speeches to cultural figures, he stated that art in China should be "like the sun from a clear sky, a light breeze in the spring."

Persecution of students and workers

In addition to cultural and scientific figures, grassroots political activists are also at risk – not always opposed to the party and even against Xi himself. However, any political thought that does not follow the Thoughts of Xi Jinping, even Maoist, is considered hostile, undesirable. For example, in 2017 a group of eight students organized a reading club focused on left-wing political thought and Maoism. Also, the meetings were devoted to trade unions and organization in the workplace: students were interested in working conditions and often visited factories on research visits, organized cultural events for workers, for example, open dance or singing lessons. On November 15, 2017, six students were detained during a regular meeting of the reading club. Two more were detained within a few weeks. Two students were arrested, one of whom, Zhang Yunfan, was illegally taken to an unknown destination after the arrest period expired without filing a case. Subsequently, he admitted that he was forced to sign a confession of "radical ideas" and organizing political collusion. As a result, Yunfan spent 6 months in detention until he was released for health reasons.

Any political thought that does not follow the thought of Xi Jinping is considered hostile

A similar wave of arrests occurred in 2018. Student activists, including young Maoists, were massively detained in several Chinese cities at once. According to testimonies, the police also took away random passers-by who happened to be near the students. Zhang Shenye, a student at Peking University, said he was attacked from behind and taken to a police car by people without shoulder straps. At least 8 other activists also spoke about the detentions. After some time, Zhang was released, which was preceded by open letters from academics and students from all over China.

Another high-profile case occurred with JASIC, a manufacturing corporation that owns factories all over China. A worker was fired at a factory in Shenzhen: his colleagues, who regularly faced poor working conditions, delays, mandatory unpaid overtime and low wages, tried to form a union, but their request was rejected by the United Federation of Trade Unions. Despite this, the workers decided to form their own trade union against the decision of the Federation. JIASIC responded by trying to put pressure on employees, which led to days of workers' protests. News of the workers' problems and the refusal to form a union quickly spread through the media and social networks. The protests were soon joined by students, activists and members of independent left organizations, as well as "neo-Maoists", including from the largest left forums Utopia and Maoflag. The protests were also supported by more well-known, mainstream activists, including academics and Chinese #MeToo activists. At the same time, large social media accounts and chats related to the protests began to appear, and activists began to spread the #epochpioneer hashtag dedicated to the protest against JIASIC and the left movement in general.

A few days later, the police broke into the apartment where the students and workers gathered, detaining all 50 people who were there. Some leaders of the movement, such as Peking University student Yue Xin, who previously wrote an open letter to Xi Jinping, were taken away to an unknown destination and subsequently reported missing. The whereabouts of some of the detainees are still unknown, although it is assumed that they, along with other leaders of the movement and account administrators – for example, epochpioneer – were sent to re-education camps.

Re-education camps

However, more radical movements are suppressed even more severely by Xi. Entire ethnic groups and regions, namely the Uighurs and the province of Xinjiang, fall under the “cleansing”. Xinjiang is a large region in northwestern China, about half of whose population is made up of Uyghurs, a small Turkic people, predominantly Muslim. Approximately since the beginning of the 1990s, the problem of Uyghur separatism began to be discussed in the media, and since 2001, against the backdrop of the September 11 attacks, the threat of “Islamic terrorism” has also been discussed. Indeed, at that time, a somewhat organized separatist movement in Xinjiang existed and was responsible for several violent actions. For example, for the armed uprising in Baren in 1990, which consisted of about 200 men who were looking for comrades in mosques. Or for a series of explosions in 1992–1993 and, finally, for a large cluster of uprisings in 1996–1997, when mass protests began and several explosions took place in connection with China's entry into the SCO (“Shanghai Five”) and the start of an operation to capture the separatists. . Several assassinations of Uyghur politicians were reported at the same time, but the perpetrators are still unknown.

Entire ethnic groups and regions fall under the “cleansing”, namely the Uyghurs and the province of Xinjiang

The only source of separatist sentiment is difficult to trace, but there are two main factors. Firstly, this is the very existence of Xinjiang as an autonomous region, because the emergence of autonomous regions often leads to the emergence of an autonomous identity and separatist sentiments. Secondly, despite the formal recognition of autonomy, the region has almost no de facto independence, which causes discontent. True, real protests rarely break out. The uprisings of 1996-1997 were the last major event in the history of violent Xinjiang separatism – or Xinjiang separatism in general – for several years, after which a noticeable surge of discontent did not occur until 2009.

Everything changed for the Uyghurs in 2014, when Xi announced the start of a "people's war on terror." In 2016, Chen Quanguo, the former head of Tibet, was appointed to the post of party secretary for Xinjiang, where he was engaged in “appeasement”, primarily, of course, through strict measures of social control. This appointment was not accidental: Chen not only showed himself to be a tough manager who does not shy away from extreme measures, but also a loyal and close ally of Xi Jinping. Quanguo immediately began to fulfill the goals set by the Chairman on the "war on terrorism". Shortly after his appointment, a comprehensive surveillance system was put in place and mass detentions of Uyghurs began .

The main innovation was the re-education camps for Uyghurs – in fact, prisons where "unreliable elements" are temporarily sent. Although the Chinese government claims that only criminals in dire need of re-education end up in the camps, academics and artists have also been reported arrested. The number of camps increased dramatically in 2017, with 15 new prisons built. Rare third-party observers who have been in the camps, for example, forced to “teach” there, talk about bullying and torture. According to them, the prisoners are beaten, tortured with water and raped. According to the same reports, the cells of the camps are often overcrowded – the number of people arrested far exceeds the capacity of the prisons.

По некоторым сведениям, основную часть «перевоспитания» составляют просмотр и заучивание речей Си Цзиньпина и прочих политических деятелей Китая. Помимо этого, заключенным читают лекции о вреде ислама, требуют отказаться от родного языка и публично отречься от их вероисповедания.

Существуют свидетельства и о прямом геноциде — попытках китайского правительства искусственно регулировать популяцию уйгуров. Так, некоторые интернированные рассказывали о том, что в лагерях их принуждают пройти стерилизацию; а открытые данные сообщают , что уровень стерилизации по региону в 8 раз выше, чем средний по Китаю. Значительно упала и рождаемость в регионе. Правительство отрицает подобные обвинения, но не стремится предоставить объяснения. Обвинения в нарушении прав человека и геноциде уйгуров Китаю предъявили уже несколько западных стран. ООН вместе с тем предоставила доклад со свидетельствами нарушения прав человека в Синьцзяне. Несмотря на нехватку материальных доказательств некоторых нарушений и отсутствие полноценного доступа к лагерям, ряд свидетельств достаточен для того, чтобы сделать вывод о систематическом нарушении прав человека.

Иллюзии сопротивления

Совсем не удивительна и приверженность правительства к политике Zero COVID. «Динамическая очистка» с китайской спецификой отличалась беспрецедентной жесткостью мер с самого начала (Lu et al, 2021 ) . Она включала в себя строгие требования по самоизоляции, массовые и продолжительные локдауны, иногда распространявшиеся на целые города, контроль над перемещениями граждан при помощи камер и специальных приложений, а также массовые тестирования и усиленный контроль границ между регионами. Не должно удивлять и то, что результатом такой политики стали самые массовые со времен площади Тяньаньмэнь протесты, о которых The Insider писал ранее. Менее типично то, что в этот раз правительство пошло на уступки и вместо асимметричного ответа резко отменило большую часть ограничений.

У некоторых наблюдателей такой исход событий вызвал небывалый оптимизм. Они говорят о новой политике «открытости» Китая, демократическом повороте в политике Си Цзиньпина. Однако пока говорить о какой-либо оттепели нет никаких оснований. За все годы правления Си Цзиньпин продемонстрировал две ключевые особенности. Во-первых, верность принципу «цель оправдывает средства», где целью является укрепление режима личной власти. Во-вторых, при необходимости он способен проявить гибкость и прибегнуть к демократическим, на первый взгляд, механизмам. Из-за массовых протестов против ZERO Covid такая необходимость возникла, и Си сделал шаг назад. Но пока нет никаких причин считать, что общий тренд Си на «закручивание гаек» изменится.