War feeds corruption

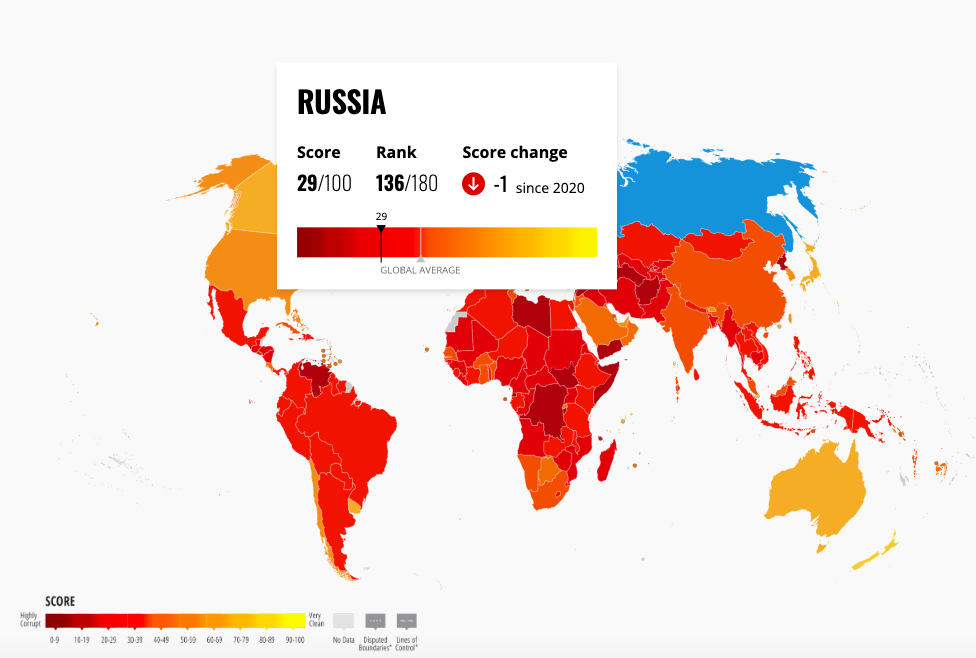

In 2021, in Transparency International’s corruption rating , Russia was in 136th place out of 180 — that is, in the last quarter of the list, where half of the countries (for example, Syria, Eritrea, Mali, Afghanistan) are engulfed in civil wars, uprisings, or involved in armed conflicts with their neighbors. Analysts estimate that the level of corruption is directly correlated with what the Foundation for Peace (a rating of failed states) calls "security threats": terrorist attacks, uprisings, insurgencies, insurgencies, coups. Most of the states that are in the same part of the list with Russia in terms of perception of corruption are located very low in the ranking of state failures. This is because they cannot maintain order in their territories: their armies and police are plagued by corruption and have difficulty containing emerging threats.

When a country is embroiled in a conflict, the corruption-related deterioration in the effectiveness of the army leads to its stretching and, paradoxically, it becomes beneficial to army officials. As Philippe LeBillon, who studies the political economy of war at the University of British Columbia, points out, war creates additional conditions for illicit enrichment. Defense contracts, payments to non-existent soldiers, command-sanctioned looting, parallel imports, the emergence of black markets, and the immunity of ruling groups all provide the perfect breeding ground for various corruption schemes and abuses. The war makes the elite groups that have received the most benefits and influence interested in continuing it indefinitely. It is enough for them to keep the effectiveness of the army at the minimum level that does not allow them to lose.

It is beneficial for the military to prolong the conflict by keeping the effectiveness of the army at a minimum

In this regard, Le Billon believes that corruption can also be used to end the conflict, making peace more beneficial for the parties involved in it. For example, in the 1990s in Mozambique, the RENAMO nationalist rebel movement was offered payments from a $10 million trust fund created for this by the international community, permission to collect taxes from businesses in its zones of control and a promise to include its representatives in the government and parliament, until then controlled by the one-party communist regime of the FRELIMO party. The latter is supposed to have given the members of RENAMO a share in all illegal transactions made in the country. Since neither RENAMO nor FRELIMO were any longer able to win a decisive victory, they agreed to the proposed terms, which ensured their peaceful coexistence for more than twenty years. Although a very corrupt two-party regime of limited democracy was established in the country, where FRELIMO always received a majority in parliament, RENAMO remained a legal opposition, receiving its corrupt dividends.

Corruption breeds wars

The military budget, due to the closeness of many of its parts, even in peacetime is a tasty morsel for those who like to cut off state money. A group of researchers from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) analyzed the correlation of the Corruption Perceptions Index with military spending and concluded that a high military budget is associated with poor governance. Vito Tanzi, head of the IMF's fiscal department, believes that up to 15% of the funds that governments spend on arms purchases go to bribes.

Up to 15% of the funds that governments spend on buying weapons go to bribes

Autocracies maintain power largely through violence and corruption. The increase in military budgets makes the military interested in maintaining the regime. At the same time, this increase in itself creates incentives to start a war, because, on the one hand, the civilian authorities want to know that they are not in vain investing in defense, and on the other hand, the military, who increase their influence through injections into army, they want to test weapons, show the validity of cash injections and demonstrate the need for further budget increases.

Most studies of the relationship between war and corruption focus on internal conflicts and do not address conflicts with neighboring countries. Nevertheless, they can be judged by studies of the influence of the type of political regime in the country on corruption and on the propensity to go to war.

The Soviet Union was a party autocracy, that is, a regime in which power was dispersed in the hands of the party bureaucracy. After the collapse of the USSR, Russia and Ukraine became transit regimes, somewhere between democracy and autocracy. Ukraine has been largely democratized all this time, while Russia, on the contrary, has been moving towards a personalist autocracy, where power is concentrated in the hands of one person.

Russia in this transformation was largely negatively affected by the "oil needle" and the rise in prices for raw materials in the early 2000s. As studies show , a significant share of natural resources in state revenues is highly likely to lead to the establishment of an authoritarian regime. In such countries, economic growth does not depend on the development of institutions (such as the protection of property rights or the separation of powers) and human capital, so that elites and citizens prefer not to produce goods and services that stimulate the growth of government tax revenues, but to share the oil rent. by twisting economic legislation in their favor. Mining is regulated by the state, which leads to the concentration of power and the merging of political and economic influence. Therefore, the authorities even hinder the development of non-resource-oriented industries – after all, they create elites that are independent of the extraction of resources and, accordingly, of the power of the autocrat, who can begin to compete with them.

Corruption becomes the main way to distribute resources and buy the loyalty of key groups of elites and the population in such regimes. At the same time, the opposition's task of coordinating efforts is made more difficult by the fact that the authorities can simply buy and co-opt groups that are gaining influence.

Dictatorship and corruption complement each other. As research by Hanna Fjelde and Havard Hegre of Uppsala University shows, corruption helps authoritarian leaders concentrate power and makes such a regime more sustainable. Another study by Fjelde demonstrates that the presence of oil rent further stabilizes corrupt regimes. Corruption, on the contrary, destabilizes democracies, so the authorities will seek to get rid of it, otherwise they risk ending up in a situation of civil conflict, which can provoke a transition to another type of regime. The high level of corruption forces transitional regimes to remain transitional, preventing them from becoming either full-fledged democracies or full-fledged autocracies.

Of all types of authoritarian regimes, personalist autocracies (and besides them, there are also party dictatorships, military juntas and monarchies) are the most unstable , corrupt and prone to conflict . The power in them is built around the autocrat, and not on the basis of institutions, so corruption becomes the main tool of governance. However, institutions also protect the ruler himself, so if they do not work and everything in the country is decided by force and money, then opponents have more temptations to seize power by force. The task of the dictator in this case is to maintain such a situation in which no one in the country had more strength and money than him, so that potential rivals could not unite. For the latter, according to a study by political science professor Eric Uslaner of the University of Maryland, corruption is especially helpful because it destroys the trust of the people of the country in fellow citizens, society as a whole and the state, forcing them to trust only a narrow circle of acquaintances.

Corruption destroys the trust of the inhabitants of the country in fellow citizens, society as a whole and the state

Konstantin Sonin, a Russian economist who previously taught at the NES and the Higher School of Economics and now works at the University of Chicago, believes that the longer a dictator remains in power, the more often he has to resort to power, he himself will be repressed. Because of this, according to Sonin, over time, the autocrat begins to prefer to surround himself with loyal people, rather than competent people, because the latter can be a danger to him. However, such a replacement leads to a deterioration in the quality of control and an increasing number of increasingly dangerous errors, thus destabilizing the regime. Actually, Sonin considers the invasion of Ukraine to be Putin's biggest mistake.

Barbara Geddes, Joseph Wright, and Erica France's classic study of authoritarian regime change confirms that autocrats' fears are not unfounded. In 69% of cases, the fall of a personalist regime ended in the assassination, exile or imprisonment of the dictator. As the authors note, dictators who fear punishment after being removed from power tend to start wars to prevent it. This is despite the fact that losing a war increases the likelihood of an autocrat being overthrown. Military action can help them distract citizens from internal problems, introduce emergency measures that prohibit criticism of them, shift the responsibility for the deterioration of life to the enemy, and send competitors to the front.

In 69% of cases, the fall of a personalist regime ended in the assassination, exile or imprisonment of the dictator

Most often personalist autocracies are at war with democracies –democracies with democracies and autocracies with autocracies are at war quite rarely. Transitional regimes, due to their instability, are more likely to be drawn into conflict than established democracies and autocracies. And although democracies often initiate conflicts themselves, so it is impossible to call democracy a guarantor of peace, it is still more often the latter who become the initiators in a pair with personalist autocracies. According to a team of researchers led by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, who uses game theory for political forecasting, this is due to the absence of institutional restrictions in autocracies and the concentration of power in one hand. Dictators need to convince fewer people to go to war. They do not trust their advisers, therefore, unlike democratic governments, they choose conflicts less carefully and lose more often. However, autocracies care little about domestic public opinion, they are much less sensitive to economic and human losses than democracies, so they are ready to wage wars for much longer.

Corruption has indeed largely been the reason for the Russian invasion of Ukraine. For years, Vladimir Putin has used it to concentrate power in his own hands and destroy institutions that could have prevented war. She pushed him to constantly increase the military budget to maintain the loyalty of the military, while simultaneously creating the illusion of the omnipotence of the Russian army and stimulating the desire to test it on the battlefield. It also creates incentives for the Russian elites to continue the senseless and obviously lost war, since it allows them to profit from government orders and the administrative chaos generated by the war, and also helps to retain power.

How effective are sanctions?

To what extent can the greed of the Russian elites be used to split them in order to end the war? Over the years, corrupt elites have been exporting most of their wealth to the West because they knew that their property was not protected in Russia. Sanctions have deprived many of them of a significant part of their accumulated property. However, most experts note that the restrictions have not yet had a significant effect, since the conditions for their removal have not been spelled out.

Western officials make it clear that sanctions could be lifted in the event of the withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine, but this condition is not fixed anywhere and is poorly targeted: those parts of the Russian elites that, in theory, could influence the decision to withdraw troops, have not so much assets abroad, and those most affected by the sanctions have no real political influence. At the same time, they could do something to end the war in exchange for the promise of security and the return of assets, but the demand to end the war seems unattainable to them and pushes only to inaction.

Scholars David Cortright and George Lopez of the Institute for Peacekeeping Studies at the University of Notre Dame analyzed the effectiveness of all international sanctions applied in the 1990s and concluded that the main conditions for their success were the commitment of the imposing countries to comply with the sanctions regime and the creation of positive incentives to get out of the sanctions . Well-defined conditions for their removal from individuals, such as material support for the Ukrainian army or the Russian anti-war movement, would create incentives for Russian elites to act. In addition, the involvement of the oligarchs in anti-war activity would break their ties with the Putin regime: the elite would become additionally interested in regime change and ending the war.