"Soviet Ark"

Demographers and historians traditionally divide emigration from the USSR into three waves. The first (1918-1922) – those who fled after the revolution. During this period, according to various estimates, from one and a half to three million people left the country. The second wave (1941-1944) includes citizens of the USSR who ended up on the territory of the Third Reich during the war – usually as Ostarbeiters or prisoners of war – and then refused to return. Although this wave was quite numerous (some historians believe that there were no more than 700 thousand “defectors”, others – that one and a half million or even more), it turned out to be the most inconspicuous. Fearing that they might be extradited to the USSR, where camps were most likely waiting for them, the emigrants tried not to draw attention to themselves. The third wave (1948-1989) refers to the entire emigration of the Cold War period. A significant part of them are Jews, who were finally allowed to leave by the Soviet authorities in the 1970s. This wave is not too numerous – only about half a million people.

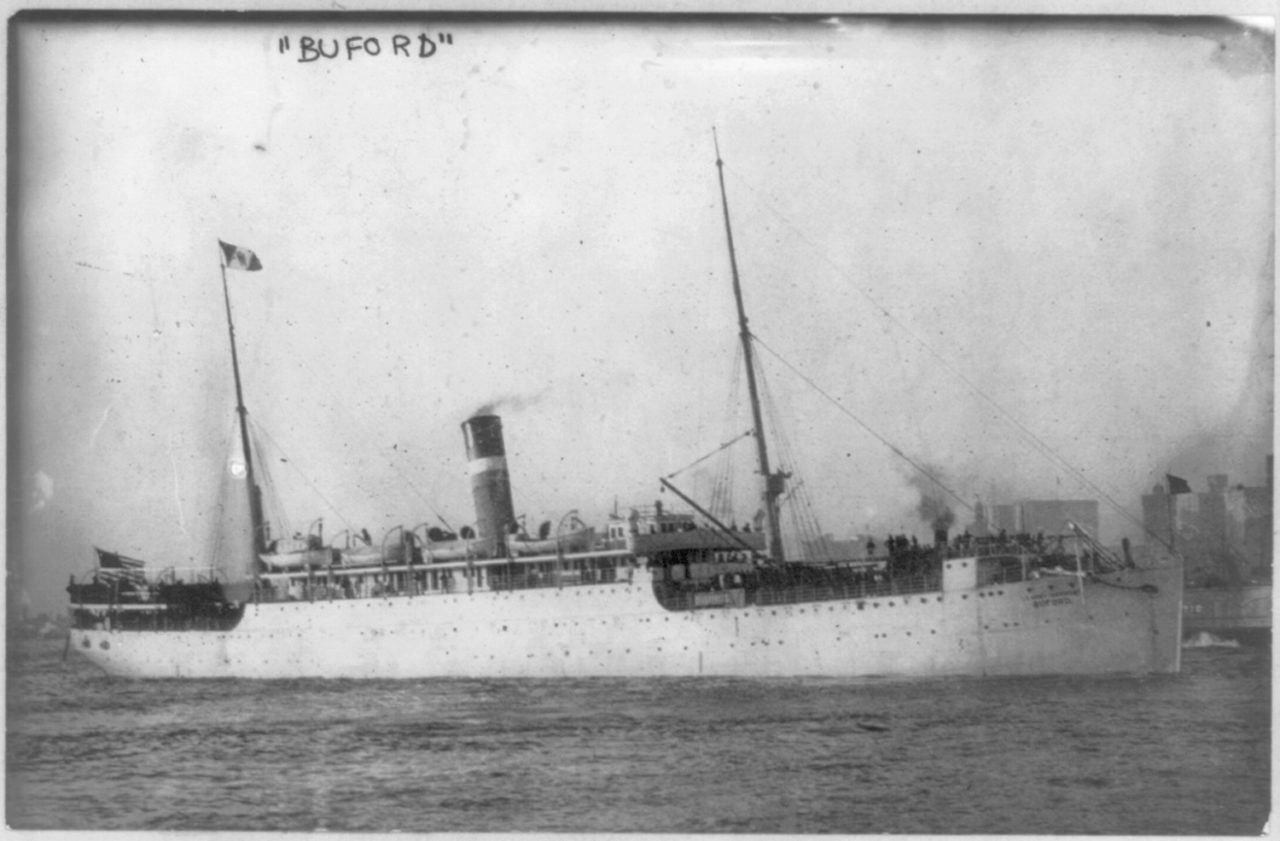

The first to return to Soviet Russia were emigrants sympathetic to the communists, who had left the country before the First World War. True, not all of them came of their own free will. So, three years before the Soviet authorities sent politically unreliable intelligentsia abroad in 1922, the American authorities did about the same thing with communists who came from the Russian Empire. It all started with Woodrow Wilson passing the Sedition Act in 1918, which allowed, among other things, the deportation of radical immigrants. Soon, Attorney General Alexander Palmer, along with the immigration authorities, using the new law, opened a real hunt for trade unions and communist organizations. As a result of the so-called " Palmer raids ", by the end of 1919, 249 immigrants from the Russian Empire were arrested, suspected of having links with the communists. Most of them were indeed members of the anarcho-syndicalist émigré organization "Union of Russian Workers of the USA and Canada", the communist and socialist parties, but a few people had nothing to do with politics at all. The detainees were first placed in an immigration prison, and on December 21, 1919, they were put in the hold of the army ship Buford and sent under escort through Finland to Soviet Russia. American newspapers immediately dubbed Buford the "Soviet (or red) ark."

On the Soviet-Finnish border, the deportees were met by a Soviet delegation headed by the secretary of the Petrograd City Committee of the RCP(b). However, further arrivals were waiting for a complete disappointment. The most famous passengers of the "ark", political activists Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman , hastily left the country after the government's harsh suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion in 1921. They soon published unflattering memories of Soviet Russia. Many others who returned later were arrested.

Prosecutor Palmer was going to send a few more "arks" to Russia, but this never happened. Firstly, even the first deportation cost the country too much. And secondly, soon a new head appeared in the immigration service, who turned out to be much more loyal to candidates for expulsion.

The return of white emigrants

Already in the first years of Soviet power, the government began to think about the return of "class enemies". In November 1921, a decree was issued "Amnesty to persons who participated as ordinary soldiers in the White Guard military organizations":

“The Soviet government knew that thousands of Russian working people were being drawn into the struggle against the worker-peasant power by means of deceit and violence on the side of the tsarist generals, landowners and manufacturers. These deceived people were brought into battle for a cause alien to them, and when they had to find themselves in a foreign land, they were left to the mercy of fate. They have now been thrown out of their native villages, villages and villages. A cruel fate scattered them to different parts of the world. Constant deprivation, systematic mockery of Russian and foreign White Guards, hard labor, illness and death in a foreign land – this is the fate of those who succumbed to the provocation of the enemies of the workers and peasants.

The decree promised a full amnesty to persons "by deceit or forcibly drawn into the struggle against Soviet power" – but so far only to ordinary people and only to those who were currently in Poland, Romania, Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia. The officers who proved their loyalty, however, also had the opportunity to return, but each such case was considered separately, through appeals to the Soviet embassies. In 1924, the circle of amnestied expanded: now the Soviet government "forgave" those White Guards who, after the Civil War, settled in China and Mongolia.

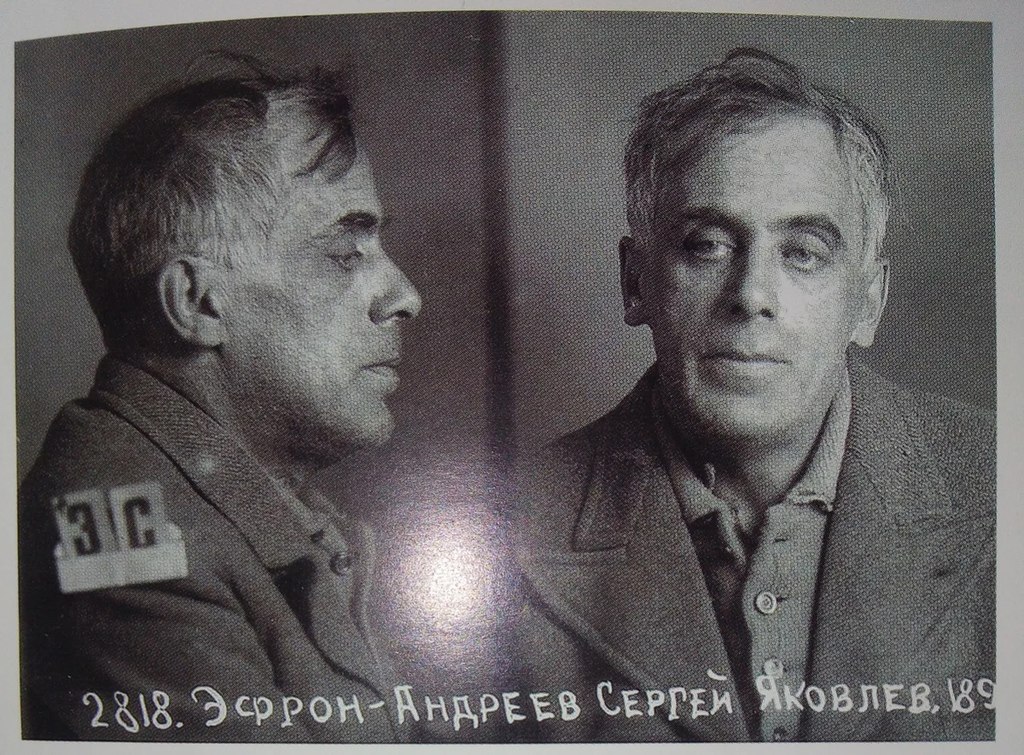

Soviet agents were active in the centers of deployment of emigrants: they delivered propaganda literature, published letters from those who had already repatriated with stories about how wonderful life was for them under the Soviets. In the centers of concentration of white émigrés, Homecoming Unions began to appear – organizations that helped those who left to return to Soviet Russia. In addition, the Unions carried out propaganda work: they distributed leaflets, printed their own newspapers, organized meetings, showed films, and “exposed the slander” of the emigre press. In Paris, Sergei Efron, the husband of Marina Tsvetaeva, became one of the activists of the Union for the Return to the Motherland in the 1930s. His further fate (arrested in 1939, shot in 1941) is an eloquent illustration of what awaited many "returnees" to their homeland.

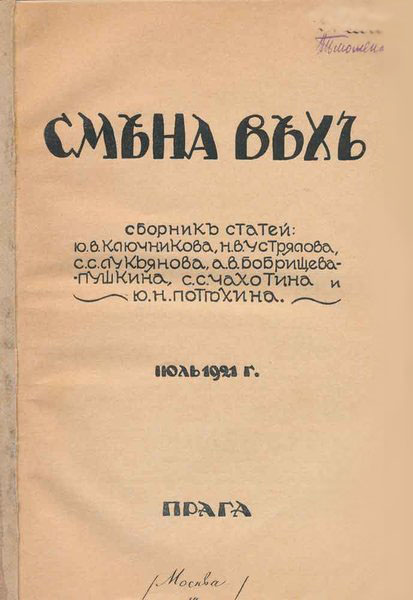

The Bolsheviks and the Smenovekhites , an emigre movement whose ideologists called for reconciliation and cooperation with Soviet Russia, were actively supported. The name of the movement comes from the collection "Change of milestones" published in 1921, where the main ideas of the movement were outlined. According to the Smenovekhites, the victory of the Bolsheviks was historically natural, it is time for the white movement to recognize it and stop fighting, the intelligentsia should be with its people, and therefore with the Bolsheviks, since the people have chosen them. “After all, it is clear as God's day that Russia is reborn. It is clear that the worst days have passed, that the revolution is spontaneously turning from a force of decay and disintegration into a creative and constructive national force,” Nikolai Ustryalov, one of the ideologists of the movement, optimistically wrote . True, the cooperation turned out to be short-lived: the Bolsheviks did not like the idea of the Smenovekhites about the “rebirth” of Soviet power.

There are several reasons why the Bolsheviks needed emigrants. First, in the 1920s, when the young country did not yet have a full-fledged personnel training system, it really needed qualified specialists in all areas. And secondly (and many historians consider this reason to be the main one), for propaganda purposes. People who lived in the West and chose socialism are a convincing argument for the superiority of the Soviet way of life.

However, this wave of re-emigration did not become massive. It is known that many White Guards did not trust the promises of the Bolsheviks too much. The story of the army of Baron Wrangel was still fresh in my memory: in 1920, the Bolsheviks published an appeal " To the officers of the army of Baron Wrangel ", promising a complete amnesty to everyone who would go over to the side of Soviet power. However, after Wrangel left the Crimea, the officers and soldiers who remained there became victims of the massive red terror.

In addition, the policy of the Soviet government towards emigrants was rather inconsistent. And the conditions under which it was proposed to return were not very tempting. In the same letter where Dzerzhinsky calls for the return of emigrants, he suggests :

“The specialists we need to give individual forgiveness and admission to Russian citizenship so that they undertake to work for a certain time (1-2 years) where we indicate, so that they prove their sincerity of repentance.”

No one was going to return the property confiscated by that time. It was also important that the position of the majority of emigrants in relation to the USSR was irreconcilable, and they considered any cooperation with the Soviets (not to mention the return) as a betrayal.

And yet, between 1921 and 1930, about 180,000 emigrants did return. At the same time, the peak of re-emigration occurred in 1921. True, for the most part they were peasants or Cossacks, and not those "specialists" on whom Dzerzhinsky counted. It is impossible to trace the fate of all the “returnees”, but it is known for sure that during the years of the Great Terror, many nevertheless suffered for their White Guard past: forgiveness turned out to be temporary.

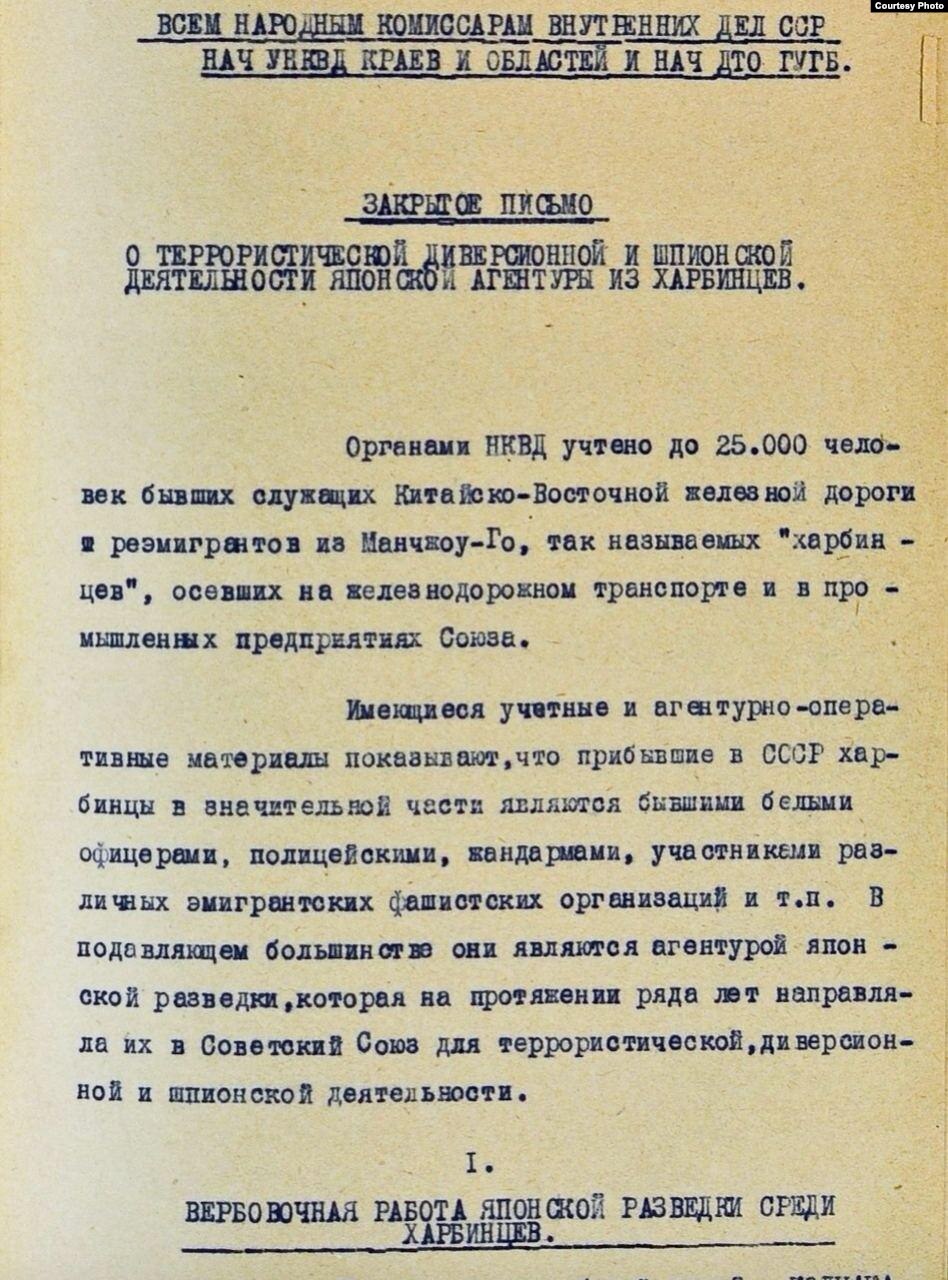

A striking example is the story of employees of the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER) who returned to the USSR. The railway that connected Chita with Vladivostok and Port Arthur and passed through the territory of Manchuria once belonged to the Russian Empire and was operated mainly by its citizens. After the revolution, the CER more than once became the subject of military conflicts between China and the USSR, and in the early 1930s it was sold to Japan (formally, to the state of Manchukuo created by the Japanese administration in the occupied territory of Manchuria). "Russian Harbinites" began to be massively evacuated to the USSR, introducing a simplified procedure for obtaining citizenship for this.

At first, the KVZhDintsy were positioned in the press as heroes forced to flee from Japanese aggression. They were willingly employed : in railway transport, in the chemical industry, in defense enterprises. But in 1937, the former CER residents became targets of a purge. True, the arrests of the KVZhDintsy began earlier, since 1935, but on September 20, 1937, an operational order of the NKVD No. 00593 was issued , which stated the need to "eliminate sabotage, espionage and terrorist personnel from among the "Harbinites." From that moment on, “pinpoint” repressions turned into a mass purge, the victims of which were even the children of the Chinese Eastern Railway, who were born in China. According to researcher Sergei Pudovsky, 21,000 people were sentenced to capital punishment in the course of the “Harbin case,” and 10,000 were sentenced to camps.

The fate of the six ideologists of the "Change of milestones" is also indicative. Yuri Klyuchnikov returned to the USSR in 1923. He made an excellent career: he was a professor at Moscow State University, worked as a consultant in the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, actively published, published books. In November 1937, he was accused of participating in a spy-terrorist organization; shot two months later.

Many remigrants during the years of the Great Terror suffered for their White Guard past

Nikolai Ustryalov worked in the Soviet establishments of the CER; after the sale of the Chinese Eastern Railway to Japan, he returned to the Soviet Union, was a professor at the largest Moscow universities. In June 1937 he was arrested on charges of espionage; shot in September.

Sergei Lukyanov, upon his return to the USSR, was editor-in-chief of Le Journal de Moscou, a weekly newspaper published in Moscow for a French audience, for seven years. In 1935 he was arrested "and participation in a counter-revolutionary group" and sentenced to five years; already while serving his term, he was sentenced to death "for counter-revolutionary agitation and glorification of the fascist regime."

Alexander Bobrischev-Pushkin returned to Soviet Russia as early as 1923; in the following years he worked as a lawyer. In 1933, his son was arrested and soon shot; in 1935 he was arrested and later sentenced to death himself.

Yuri Potekhin also returned to the USSR in 1923, where he was offered to head one of the departments of the Supreme Council of the National Economy (VSNKh). In November 1937, he was arrested on charges of "counter-revolutionary agitation"; shot ten days later.

Thus, of the six Smenovekhites, only one survived, Sergei Chakhotin. And even then only because he turned out to be more cautious than his colleagues and returned to the USSR only in 1958, under Khrushchev.

Repatriation after World War II

At the end of World War II, the authorities of the country, which suffered enormous human losses, faced a new task: to return to their homeland Soviet citizens displaced during the war abroad. According to the then estimates, there were about 5 million such people. For the most part they were Ostarbeiters . To this end, in 1944, an appropriate body was established – the Office of the Authorized Council of People's Commissars of the USSR for Repatriation.

Far from always this repatriation was voluntary. It turned out that many Soviet citizens did not want to return to their homeland. Some of these defectors were collaborators who collaborated with the Nazis and then voluntarily left with them. But, according to historians, there were a minority of these: prisoners of war and Ostarbeiters, not without reason, believed that repressions awaited them in their homeland.

Prisoners of war and Ostarbeiters, not without reason, believed that they were also expected to be repressed in their homeland.

To return them, the Soviet authorities had to enlist the support of the allies: the agreements of the Yalta Conference of 1945 and additional agreements signed with the French and British governments prescribed that all citizens living in the territory of the USSR at the time of the outbreak of World War II, regardless of their desire, be transferred to the Soviet authorities . At the same time, citizens who until September 1, 1939 lived in territories that were not yet part of the USSR at that time were not subject to forced repatriation. The exception is if they were accused of collaborationism.

The Allies might have feared that the Soviet authorities would artificially delay the return of American and British POWs home if they refused to extradite Soviet citizens caught in their occupation zones. According to another version , they simply did not know how to provide such a number of potential emigrants.

Soviet citizens who were in the Soviet occupation zone were sent to the USSR by default. Those who ended up in the American, British and French countries were more fortunate: if they did not want to return, they had the opportunity to impersonate residents of the territories annexed to the USSR after September 1, 1939, or as “first wave” emigrants, or hide on private apartments. At the same time, the emigrants of the "first wave" actively helped the defectors of the "second wave" to hide and at the same time defended their rights before the allies.

repatriation, although formally it should not have concerned them. One of the loudest such stories is the arrest of Vasily Shulgin. A deputy of the State Duma, a man who accepted abdication from the hands of Nicholas II, one of the ideologists of the White movement, Shulgin in the 1930s hoped that Hitler would help put an end to Bolshevik rule in Russia (like many white émigrés). But with the beginning of the Second World War, he sharply changed his views and did not cooperate with the Nazis during the war years. Nevertheless, when Soviet troops entered Yugoslavia, where Shulgin lived, he was detained, taken to Moscow, arrested and sentenced to 25 years for "anti-Soviet activities." Already 67-year-old at that time, Shulgin will survive the imprisonment, in 1956 he will be released, in 1961 he will publish the book “Letters to Russian Emigrants”, where he will admire both the Soviet communists and Khrushchev personally, in the same year he will attend XXII as a guest Congress of the CPSU, starred in the documentary " Before the Judgment of History " and died in 1976 at the age of 98. True, he will never accept Soviet citizenship – just as he had not accepted foreign citizenship before.

However, the Soviet authorities did not doze off, they identified citizens hiding from returning, sent agents to camps for displaced persons, compiled lists, and organized raids. It happened that those hiding from repatriation were simply abducted from "foreign" occupation zones and taken to the Soviet one. However, this practice still had to be abandoned – it caused too much hype. Therefore, the Soviet authorities more often acted by persuasion. The state, interested in returning as much workforce as possible to restore the country, declared the extension of all civil rights to repatriates, promised them all kinds of benefits and benefits, benefits, housing, compulsory employment and, of course, free travel to their place of residence. Sometimes letters were used from relatives of "defectors", written under the dictation of the MGB.

Researchers' estimates differ as to how many people still managed to stay in the West. Official sources underestimated this figure: according to them, there were only 450 thousand “defectors”. Historians call other figures: from 700 thousand to one and a half million.

It is interesting that in parallel with these often forced repatriates, emigrants of the “first wave” began to return actively – and absolutely voluntarily – to the USSR. World War II divided the Russian emigrants into two camps. Some believed that "against the Bolsheviks – even with the devil" (read – with Hitler). Others were convinced that if the homeland (whatever it is) is in danger, it must be supported. Тем более тогда казалось — по крайней мере, со стороны — что советская власть трансформируется. Ведь и православную церковь признали, и патриаршество восстановили, и «интернациональную» риторику сменили на патриотическую, и стали постоянно апеллировать к славной российской истории. Взять хотя бы названия появившихся в СССР в годы войны наград: орден Александра Невского, Суворова, Кутузова.

В итоге многие эмигранты были настроены на сближение с советской властью. И та охотно шла им навстречу. В 1945 году для лояльных советской власти эмигрантов устраивали приемы в советском посольстве в Париже. А 14 июня 1946 года вышел Указ Президиума ВС СССР «О восстановлении в гражданстве СССР подданных бывшей Российской Империи, а также лиц, утративших советское гражданство, проживающих на территории Франции»: эмигранты первой волны теперь могли без проволочек получить советский паспорт и вернуться на родину. Аналогичные указы были приняты и по эмигрантам, осевшим в других странах – Болгарии, Югославии, Чехословакии и Китае.

После Второй мировой войны многие эмигранты были настроены на сближение с советской властью

Однако эта волна не была массовой. В общей сложности, в период с 1945 по 1949 гг в страну въехали 106 тыс. бывших эмигрантов, но большая их часть — армяне, бежавшие в начале XX века от турецкого геноцида, и их потомки. Непосредственно “белоэмигрантов” и их детей, приехавших на ПМЖ в СССР в этот период, было всего несколько тысяч.

Судьба переселенцев этой волны также оказалась незавидной. Некоторые позже получили сроки, другие просто оказались совершенно не в тех условиях, о которых им рассказывали – но уже не имели возможности вернуться обратно. В начале 2000-х французский журналист Николя Жалло снял про французских реэмигрантов этой волны документальный фильм и выпустил книгу «Заманенные Сталиным».

Лилиан Монит-Прокопович, которая в детстве вместе с родители-репатриантами приехала в СССР из Франции, вспоминает :

«Была очень успешная работа советских дипломатов во Франции, которые на все лады расписывали зажиточную жизнь людей в первой социалистической стране».

Семья, вдохновленная советской пропагандой, вернулась в СССР в 1947 году. «Куда он попал, отец понял уже на вокзале в Пинске, когда увидел, как во что попало одетые женщины метут перрон, — вспоминает Лилиан. — Он стал искать пути возвращения, еще не понимая, что таких путей в Советском Созе просто не было». История очень типична (очень многие репатрианты, поняв, что их обманули, обращались в МИД с просьбами разрешить им уехать обратно) — с той разницей, что Михаил Монит не смирился, а попытался бежать. Во время перехода белорусско-польской границы был задеран и осужден на 10 лет.

В начале 2000-х французский журналист Николя Жалло снял про французских реэмигрантов этой волны документальный фильм и выпустил книгу «Заманенные Сталиным».

Последняя попытка вернуть эмигрантов на Родину

Последняя попытка вернуть эмигрантов случилась уже после смерти Сталина и была нацелена во многом на невозвращенцев второй волны. Их реэмиграция, по мнению историков, опять-таки имела скорее пропагандистское, чем экономическое значение. Желание советских граждан остаться на Западе било по престижу советского режима, поэтому власти очень старались убедить мировую общественность, что все советские граждане хотят вернуться на родину.

Желание советских граждан остаться на Западе било по престижу советского режима

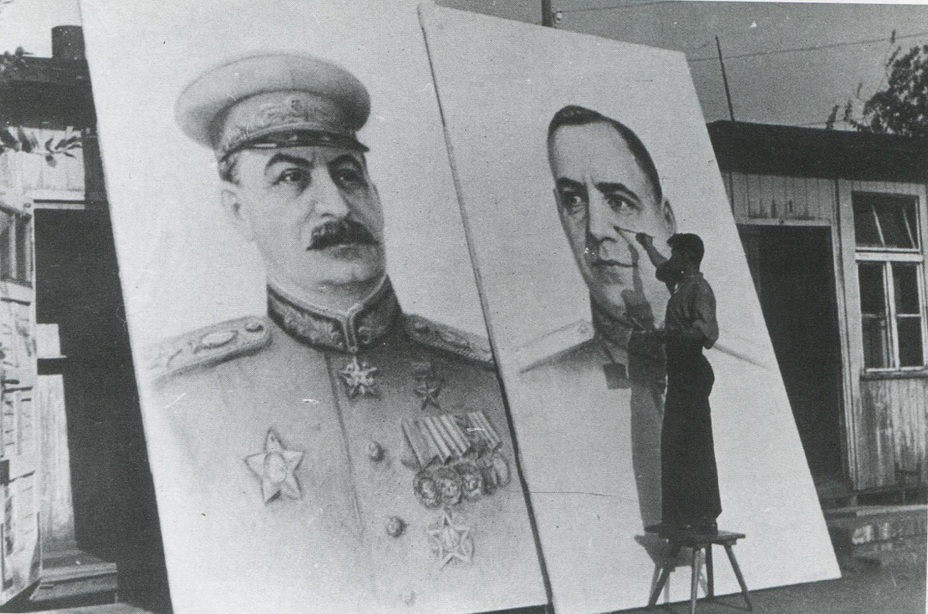

17 сентября 1955 года вышел Указ Президиума ВС СССР «Об амнистии советских граждан, сотрудничавших с оккупантами в период ВОВ». В том же 1955 году в восточном Берлине был создан комитет “За возвращение на Родину” под руководством генерала Николая Михайлова. Формально это было “добровольное объединение”, якобы созданное самими эмигрантами, но ни для кого не было секретом, что фактически комитет находился в ведении КГБ.

Комитет издавал одноименную газету, наводил мосты с эмигрантами и вел активную пропагандистскую деятельность, а Михайлов раздавал интервью западным СМИ, в красках рассказывая, как замечательно живется реэмигрантам. Даже если они сотрудничали с нацистами, родина простит всех, кто искренне раскаивается, убеждал он. Когда Комитет освоил радиовещание, пропаганда стала еще разнообразнее: тут были и музыкальные подборки с ностальгическим уклоном, и культурно-просветительские передачи, и увлекательные репортажи о советских достижениях и, конечно, трогательные рассказы о счастливой жизни тех, кто вернулся из-за границы – особенно бывших военнопленных. Иногда в передачах в качестве гостей участвовали сами реэмигранты или родственники тех, кто еще оставался за границей (или читались от них письма со слезными призывами возвращаться домой). Заканчивались передачи примерно такими призывами: «Дорогие земляки! Торопитесь возвратиться на Родину. И вы сможете принять участие в этом важном строительстве».

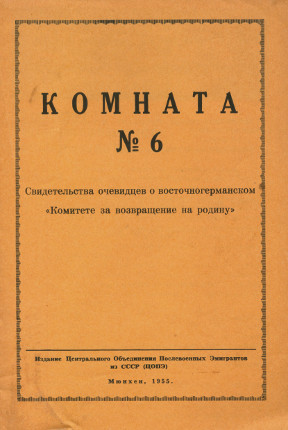

Интересно, что параллельно эмигрантские организации активно вели на Западе контрпропаганду против Комитета за возвращение на Родину. Так, Центральное объединение послевоенных эмигрантов из СССР (ЦОПЭ) в 1955 году опубликовало брошюру «Комната №6: свидетельства очевидцев о восточногерманском «Комитете за возвращение на родину». Там опубликованы рассказы тех, кто «поверили заманчивым обещаниям комитета генерала Михайлова… и решили возвратиться в Советский Союз», но «через короткий срок бежали обратно в свободный мир».

Чтобы вернуть из эмиграции военнопленных, нужно было в первую очередь показать им, что родина их больше ни в чем не винит. Поэтому 29 июня 1956 года было принято специальное постановление ЦК КПСС «Об устранении последствий грубых нарушений законности в отношении бывших военнопленных и членов их семей», где, помимо прочего, говорилось:

«Министерству культуры СССР по согласованию с Министерством обороны СССР включить в тематические планы издательств, киностудий, театров и культурно-просветительных учреждений подготовку художественных произведений, посвященных героическому поведению советских воинов в фашистском плену, их смелым побегам из плена и борьбе с врагом в партизанских отрядах. Публиковать в партийной, советской и военной печати статьи, рассказы и очерки о подвигах советских воинов в фашистском плену. Обязать Комитет госбезопасности через “Комитет за возвращение на Родину“ <…> довести мероприятия ЦК КПСС, изложенные в настоящем Постановлении в отношении бывших военнопленных, до сведения советских граждан, находящихся за границей, с целью ускорения возвращения на Родину».

Действительно, вернувшихся в СССР в тот период уже не сажали, как это зачастую случалось при Сталине. Но и обещанных материальных и карьерных благ на реэмигрантов по прибытии не сваливалось: даже обещание обеспечить их работой и жильем выполнялось далеко не всегда. Как бы там ни было, активных попыток массово вернуть бывших соотечественников на родину советское государство больше не предпринимало, очвеидно понимая всю бесперспективность этого мероприятия.