Surprisingly, Russia's path to the revival of the death penalty resembles the Italian one – but not in everything.

The death penalty was almost non-existent in the middle of the 19th century, but as the political situation became more tense, the authorities began to respond to terrorist attacks with reprisals – and executions. In Russia, the terrorists also killed the monarch, but unlike those who fell into the hands of the Italian Themis, they went to the gallows. At the beginning of the 20th century, Russia knew many terrorist attacks: ministers and governors were killed, bombs tore apart the uncle of the tsar, the extremely unpopular Moscow governor-general, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, and Interior Minister Plehve, known for his conservative views. The famous liberal and outstanding historian Pavel Nikolaevich Milyukov, who did not share the socialist views of the terrorists and their radical methods, described his reaction to the news of Plehve's death that caught him abroad:

On July 29, when I went out to meet a family returning from a morning swim, I saw from a distance in the hands of my wife a sheet of newspaper, which she waved at me with signs of great excitement. I quickened my pace and heard her voice: "Killed by Plehve!" I read the telegram. Yes, indeed, Plehve was blown up by a bomb on the way to the tsar with another report! .. And this "fortress" was taken. Plehve, who fought against the zemstvos, staged Jewish pogroms, persecuted the press, pacified peasant uprisings with floggings, suppressed by repression the first manifestations of the national aspirations of the Finnish, Poles, Armenians – manifestations that are still relatively modest – Plehve was killed by a revolutionary. He, who told Kuropatkin: "To stop the revolution, we need a small victorious war." The war was neither small nor victorious; Before Plehve's death, it was precisely the Russian troops that experienced defeat – and here is the answer of the Russian revolution! Here, obviously, the Russian struggle against the "besieged fortress" of the autocracy entered a new phase. How will the government respond to a new blow? .. Now the joy over his murder was universal. Another collaborator of Osvobozhdenie spoke on this subject in the same issue of the "moral unnaturalness of the feeling of joyful satisfaction" caused "in the hearts of many Russian people" by Plehve's disappearance; but he admitted that this feeling "is quite natural under the unnatural conditions of Russian life."

Reading these lines, you understand how great was the mutual anger on both sides, and again you think: who knows, maybe Tolstoy's naive and idealistic letter with a proposal to pardon the People's Will was not so naive after all? Perhaps it would lead to moral cleansing, which Russian society lacked so much?

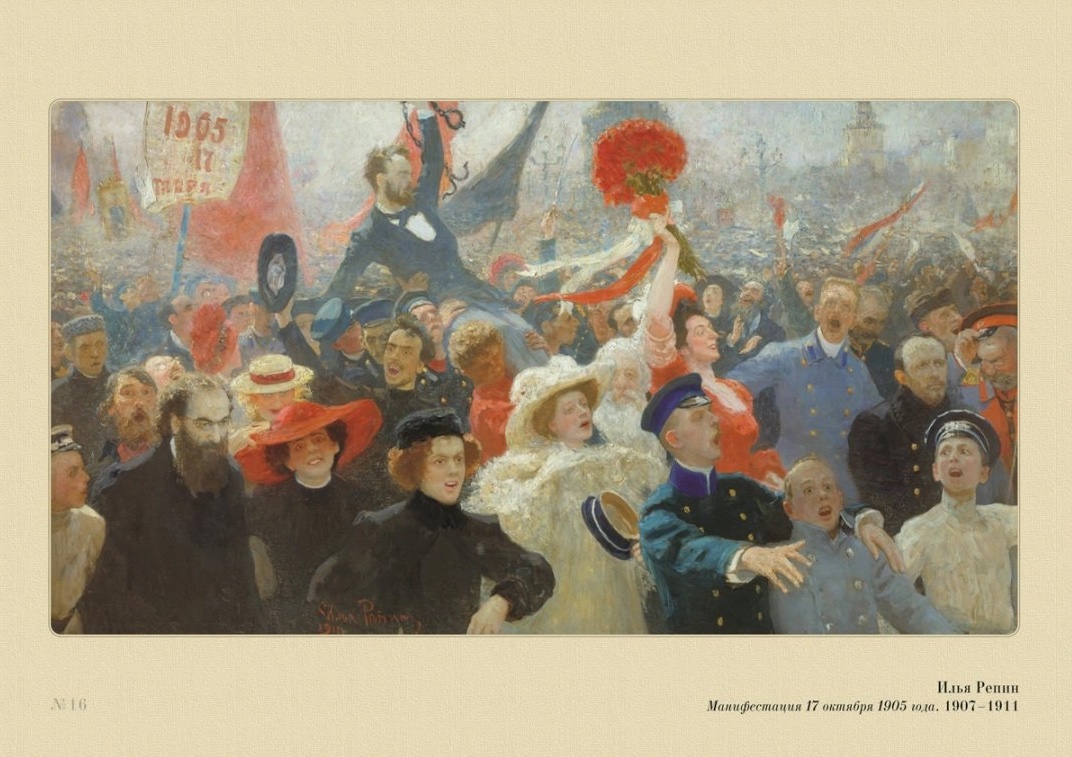

A few months after the assassination of Plehve, on January 9, 1905, troops in St. Petersburg shot down a peaceful demonstration of workers. Again blood was shed. The revolution has begun. Landlord estates in different parts of the country were on fire, factories stopped, the uprising on the battleship Potemkin led to violent pogroms in Odessa. In the fall, an opportunity seemed to open up for reconciliation: the manifesto of October 17 promised a political amnesty and the convocation of a legislative Duma, but passions were still seething. The publication of the manifesto caused jubilation and demonstrations under red flags throughout the country, and in response, Black Hundreds protested, Jewish pogroms, and left-wing journalists were killed. In December 1905, an uprising began in Moscow, which, of course, was brutally suppressed. In Sevastopol, the rebellious sailors of the cruiser Ochakov were shot.

It should be noted that in Russia an important role in the process of general brutality was also played by the war – and not even one. The events of 1904–1905 took place against the backdrop of the Russo-Japanese War, which today is overshadowed for us by subsequent wars, much larger and bloodier. And for the people of the early twentieth century, for a generation that did not know wars at all – after all, before that, the last time Russia fought in 1877-1878 – Port Arthur, Liaoyang and, of course, Tsushima were a shock. “The clouds blew through the bloody Tsushima foam,” Akhmatova wrote many years later. She spoke more than once about the great significance of the Russo-Japanese War for her generation.

Much harsher and brighter this was reflected in the story of Leonid Andreev "Red Laughter", whose hero goes to war, shown by a terrible bloody phantasmagoria, an incredible and cruel madness that drives the narrator and many others crazy. The story, written in the autumn of 1904, ends with a completely apocalyptic scene:

We went to the window. From the very wall of the house to the eaves, an even fiery red sky began, without clouds, without stars, without sun, and went beyond the horizon.

And below, under it, lay the same even dark red field, and it was covered with corpses. All the corpses were naked and with their feet turned towards us, so that we saw only the soles of the feet and the triangles of the chins. And it was quiet – obviously, everyone died, and there were no forgotten ones on the endless field.

“There are more of them,” said the brother.

He also stood at the window, and everyone was there: mother, sister and everyone who lived in this house. Their faces were not visible, and I recognized them only by their voices.

“It seems,” said the sister. — No, really. You look. True, there seemed to be more corpses. We carefully looked for the reason and saw: next to one dead man, where there used to be a free place, a corpse suddenly appeared: apparently, they were thrown out by the earth. And all the free gaps quickly filled up, and soon the whole earth brightened from the pale pink bodies lying in rows, bare feet towards us. And the room brightened with a pale pink dead light.

“Look, they don’t have enough room,” said the brother. The mother replied: One is already here.

We looked around: behind us on the floor lay a naked pale pink body with its head thrown back. And now another and a third appeared next to him. And one by one the earth threw them out, and soon regular rows of pale pink dead bodies filled all the rooms.

“They are in the nursery too,” said the nurse. – I saw.

“We have to go,” said the sister.

“But there is no passage,” said the brother. — Look.

True, with their bare feet they already touched us and lay tightly hand to hand. And so they stirred and trembled, and rose all the same regular rows: it was new dead people who came out of the earth and lifted them up.

"They'll choke us!" – I said. – Save yourself out the window.

– You can't go there! shouted the brother. – You can't go there. Look what's there!

… Outside the window in the crimson and still light stood Red Laughter itself.

The earth giving up its dead is an image of the Apocalypse, an omen of the end of the world. It seems that just such sensations were experienced in Russia – someone is stronger, someone is weaker.

The summer of 1906 brought a new round of violence. On August 12, a bomb exploded, brought by terrorists to a dacha on Aptekarsky Island, where the new Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin lived, whom the revolutionaries considered (quite reasonably) to be the initiator of the dispersal of the State Duma. More than 100 people were injured in the explosion – several dozen died. Stolypin's little daughter was thrown from the balcony by an explosion, and she remained an invalid. Here is how Maria von Bock, one of Stolypin's daughters, described what happened in her memoirs:

Instantly there was a deafening explosion… Most of the dacha was blown into the air. Heartbreaking cries of the wounded, the groans of the dying and the piercing cry of the wounded horses who brought the criminals were heard. The wooden parts of the building caught fire, the stone ones rained down with a roar…

The revolutionaries themselves, Zamyatin and the porter were torn to shreds. In addition to them, more than thirty people died right there, immediately, not counting those who died in the coming days from wounds. The explosion was so powerful that not a single whole piece of glass was left in the windows of the factory located on the other side of the Nevka … Near the office, in the living room, literally not a single thing survived, not a single wall or ceiling, but remained in its place stand a small table with an untouched and not even dusty framed photograph. There were many such incomprehensible phenomena during the explosion. One of the rescued, who introduced himself as dad, later told me how he approached the governor he knew before the explosion and had just managed to start talking to him when he saw his interlocutor without a head.

Natasha and Adya, who, as was said, were on the balcony above the entrance at the time of the explosion, were thrown onto the Embankment. Natasha fell under the feet of the horses harnessed to the dilapidated landau of the killers. It was covered by some kind of board, which was trampled on by horses raging with pain. Then a soldier found her. She was unconscious…

A week later, the Regulations of the Council of Ministers on military field courts were adopted. Martial law or a state of emergency was introduced in 82 out of 87 provinces, which means that courts-martial could quickly try the cases of those accused of “robbery, murder, robbery, attacks on military, police and officials and other grave crimes, in those cases when there is no need for additional investigation beyond the evidence of the crime. The court was short and cruel and was administered by a composition of the chairman and four members of the court, appointed from line officers by the head of the garrison (port commander) on the orders of the governor general or commander in chief. No preliminary investigation was carried out, the verdict itself was based on the materials of the security department or the gendarme department. The court session was held without the participation of the prosecutor, defense counsel or defense witnesses behind closed doors. The indictment was replaced by an order for trial.

By personal order of Nicholas II, a clause was included in the provision, according to which the sentence was to be pronounced no later than 48 hours later, immediately receive legal force and be carried out within 24 hours by order of the head of the garrison. The convicts had the right to apply for pardon, but on December 7, 1906, the Ministry of War ordered "to leave these requests without movement."

The military field courts lasted only eight months – decisions taken during the dissolution of the Duma had to be submitted for approval after the new parliament was convened. Stolypin, of course, did not do this, realizing that the deputies would never vote for such a cruel measure. And indeed, the courts-martial caused shock and horror, throughout the country the gallows began to be called "Stolypin's ties." The authorities could explain as much as they liked that this was a “necessary defense”, Stolypin could angrily exclaim: “They need great upheavals, we need a great Russia,” but in a country that had long weaned itself from mass legalized executions, this measure was rejected. The military field courts handed down 1,102 death sentences – an average of about 137 per month, four or five a day … Not all of them were carried out, "only" 683 people were executed. Looking from today, one can smile sadly and say that in Stalin's time so many people were sometimes executed in one day, but the thing is that then, in those revolutionary years, the road was being paved to the time when mass executions would be be perceived as something normal.

Stolypin's ideas were quite understandable, logical and reasonable – to severely suppress the revolutionary movement, punish terrorists, but at the same time do everything possible to win over the rest of society to their side. For this, his great agrarian reform was needed, for this he went into a sharp conflict with the tsar and his entourage, seeking the introduction of zemstvos in the western provinces, where there was still no self-government, for this he tried – alas, unsuccessfully – to convince the tsar of the need to equalize Jews in rights with the Orthodox population.

All this was probably correct and well thought out – but on paper: 683 executed and hanged in a country where before that for a century and a half every execution was perceived as an exception – it was impossible to accept this.

Starting from 1907, courts-martial were preserved only for the military, but the use of the old articles on the death penalty for rebellion and treason, not to mention attempts on members of the imperial family, not only was not abolished, but was increasingly expanded.

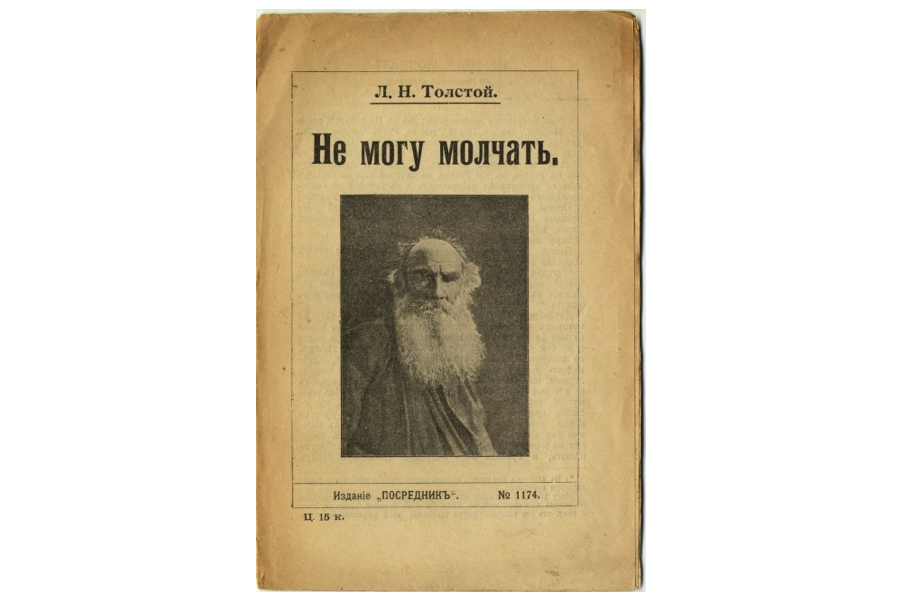

It is no coincidence that over the next few years Russian culture shook in convulsions from the horror of what was happening. Leo Tolstoy almost physically felt the actuation of everyone – everyone! – death sentence

Seven death sentences: two in St. Petersburg, one in Moscow, two in Penza, two in Riga. Four executions: two in Kherson, one in Vilna, one in Odessa.

And it's in every newspaper. And this goes on not for a week, not for a month, not for a year, but for years. And this is happening in Russia, in that Russia in which the people consider every criminal unfortunate and in which, until very recently, there was no death penalty by law.

I remember how proud I once was of this before the Europeans, and now the second, third year of incessant executions, executions, executions.

The work on the article “I Can't Be Silent” began with Tolstoy dictating into the phonograph: “No, that's impossible. You can't live like this! You can't live like this!" – and then, after writing a few more lines, he stopped, unable to continue. Then these words will appear at the end of the article: “You can’t live like this. At least I can’t live like that, I can’t and won’t.”

It was impossible to publish the article in full in Russia at that moment – excerpts from it appeared in many newspapers, and the full text was published illegally. Tolstoy was very excited and wanted to publish his article as soon as possible – or, perhaps, it would be more correct to say, a cry.

In response, the artist Ilya Repin published his appeal in the Slovo newspaper:

Leo Tolstoy, in his article on the death penalty, expressed what all of us Russians boiled over in our souls and which, due to cowardice or inability, we have not expressed until now. Leo Tolstoy is right – a noose or a prison is better than to continue silently every day to learn about the terrible executions that dishonor our homeland, and with this silence, as it were, to sympathize with them. Millions, tens of millions of people will no doubt now subscribe to the letter of our great genius, and each signature will express, as it were, the cry of a tormented soul. I ask the editors to add my name to this list.

“Better a noose or a prison than to continue silently every day to learn about the terrible executions that disgrace our homeland”

In the same 1908, when the article “I can’t be silent!” appeared, Leonid Andreev wrote The Story of the Seven Hanged Men and dedicated it to Tolstoy. The story begins with an old minister rejoicing that the police were able to track down the terrorists:

And then at night, in the silence and loneliness of someone else's bedroom, the dignitary became unbearably frightened.

He had something with the kidneys, and with every strong excitement, his face, legs and arms were filled with water and swelled, and from this he seemed to become even larger, even thicker and more massive. And now, towering like a mountain of swollen meat above the crushed springs of the bed, with the anguish of a sick person, he felt his swollen, as if someone else's face and persistently thought about the cruel fate that people prepared for him. He remembered, one by one, all the recent terrible cases when people of his dignitary and even higher position were bombed, and the bombs tore the body to shreds, splattered the brain on the dirty brick walls, knocked the teeth out of the sockets. And from these memories, his own fat sick body, spread out on the bed, seemed already a stranger, already experiencing the fiery force of the explosion; and it seemed as if the arms at the shoulder were separated from the body, the teeth fell out, the brain was divided into particles, the legs went numb and lay obediently, fingers up, like those of a dead person. He stirred vigorously, breathed loudly, coughed, so as not to resemble a dead person in any way, surrounded himself with the living noise of ringing springs, a rustling blanket; and to show that he was completely alive, not a bit dead and far from death, like any other person, he boomed loudly and abruptly in the silence and loneliness of the bedroom:

– Well done! Well done! Well done!

It was he who praised the detectives, the police and the soldiers, all those who guard his life and so timely, so cleverly prevented the murder.

The story ends with the way of the cross condemned to the gallows, and then:

The sun was rising over the sea. They put the bodies in a box. Then they took it. With outstretched necks, with madly protruding eyes, with a swollen blue tongue, which, like an unknown terrible flower, protruded among lips irrigated with bloody foam, the corpses floated back, along the same road along which they themselves, alive, had come here. And the spring snow was just as soft and fragrant, and the spring air was just as fresh and strong. And the wet, worn-out galosh lost by Sergey blackened in the snow.

This is how people greeted the rising sun.

Thinking Russia rejected, did not accept, could not come to terms with the fact that executions began to be carried out regularly in the country. But the executions continued, the revolutionaries became even more hardened, and in response there were new arrests and executions.

This is how Russia approached the First World War and the time when the Bolsheviks, who remained a small, little-known party until the beginning of 1917, were able within a few months to become the idols of thousands of people and seize power.

Of course, here we see a significant difference from the Italian situation. Mussolini and his fascists sang of the war and were proud of their participation in it. Ленин провел войну, сидя в швейцарских кафе и призывая к ее немедленному прекращению. На этом и была основана невероятная популярность большевиков в 1917 году — они требовали незамедлительно, сейчас же остановить боевые действия, и тысячи людей в окопах хотели того же.

Есть только одно «но» — прекращение войны должно было произойти не ради спасения людей, не из-за признания ценности каждой человеческой жизни. Не будем забывать, что еще в 1914 году, сразу после начала Первой мировой, Ленин призывал превратить «империалистическую войну в гражданскую» — обратить штыки против собственного правительства. Война просто должна была изменить характер, что и произошло. Вскоре после принятия Декрета о мире было заключено перемирие с Германией, начались переговоры, закончившиеся подписанием Брестского мира, но в тот момент, когда на российско-германском фронте окончательно прекратились военные действия, уже начинались столкновения между красными и белыми, а на самом деле, если быть точнее — между сторонниками большевиков и их же братьями-социалистами, и белой добровольческой армией, и махновцами, и представителями многочисленных национальных движений, и отрядами стран Антанты, и… продолжать можно еще долго. В России шла война всех против всех.

А что же со смертной казнью? Уже в 1917 году мы видим борьбу двух тенденций — желания отказаться от ужасного наказания и стремления к ужесточению наказаний, напрямую связанного с войной.

Первым председателем Временного правительства стал князь Георгий Евгеньевич Львов — известный общественный деятель, филантроп, тульский помещик и, кроме того, сосед и хороший знакомый Толстого, чьи взгляды были ему очень близки. Не случайно уже через неполные две недели после образования правительства — 12 марта — в России была отменена смертная казнь.

И точно так же, увы, не случайно и то, что уже в начале июля Львов ушел в отставку, осознав свою неспособность справиться с нарастающим хаосом. После этого он, что характерно, отправился к старцам в Оптину пустынь.

8 июля генерал Корнилов, пока что только командующий Юго-Западным фронтом, отправил телеграмму по всему фронту: «Самовольный уход частей я считаю равносильным с изменой и предательством. Поэтому категорически требую, чтобы все строевые начальники в таких случаях, не колеблясь, применяли против изменников огонь пулеметов и артиллерии. Всю ответственность за жертвы принимаю на себя, бездействие и колебание со стороны начальников буду считать неисполнением их служебного долга и буду таковых немедленно отрешать от командования и предавать суду».

На следующий день первые 14 солдат, нарушившие военную дисциплину, были расстреляны. Корнилов требовал от частей, которые отказывались воевать, выдачи зачинщиков, а бывало, что по мятежным частям открывали артиллерийский огонь.

12 июля Временное правительство уступило настояниям харизматичного генерала, и смертная казнь была восстановлена. Казнить могли только на фронте за «военную и государственную измену, побег к неприятелю, бегство с поля сражения, самовольное оставление своего места во время боя и уклонение от участия в бою, подговор, подстрекательство или возбуждение к сдаче, бегству или уклонению от сопротивления противнику, сдачу в плен без сопротивления, самовольную отлучку из караула в виду неприятеля, насильственные действия против начальников из офицеров и солдат, сопротивление исполнению боевых приказаний и распоряжений начальников, явное восстание и подстрекательство к ним, нападение на часового или военный караул, вооруженное сопротивление и умышленное убийство часового, а за умышленное убийство, изнасилование, разбой и грабежи лишь в войсковом районе армии». Тому же наказанию подлежали и неприятельские шпионы.

Уже 19 июля были расстреляны четыре солдата за братание с неприятелем, 21-го — три зачинщика бунта на Западном фронте. Давно потерявшую смысл войну приходилось продолжать с помощью кровавых мер.

При этом приговор трем мятежникам смогли привести в исполнение не сразу. «Военно-революционным судом были приговорены к расстрелу ротный фельдшер В.И.Швайкин (глава полкового комитета), ефрейтор Ф. И. Галкин и старший унтер-офицер А. П. Коковин. Комиссар III армии подполковник Постников отказался утвердить приговор, мотивируя спешной поездкой в штаб фронта. Под предлогом болезни отказался утвердить приговор председатель армейского комитета III армии. Однако приговор утвердил его «временный заместитель», солдат, один из рядовых членов армейского комитета, временно «заместивший» председателя. Приговор был приведен в исполнение в 5 часов 15 минут утра 1 августа».

Бывало, что смертный приговор восставшим солдатам вызывал новые восстания, а расстрельные команды отказывались приводить его в исполнение. Что это — распад армии под воздействием большевистской агитации, как потом будут писать в мемуарах белые генералы? Или просто невозможность людей смириться с бессмысленностью войны и кровавыми казнями?

19 июля Корнилов был назначен главнокомандующим и — в отчаянной попытке восстановить дисциплину в разваливавшейся армии — начал убеждать Керенского ввести смертную казнь и в тыловых частях.

Можно представить себе яркую картинку: добейся Корнилов своего, не испугайся в последние дни августа Керенский, не объяви он харизматичного конкурента предателем революции — и не провалился бы «корниловский мятеж», Корнилов стал бы диктатором, навел железной рукой порядок, приструнил, арестовал, казнил большевиков, заставил под угрозой расстрела солдат идти в бой и завершил бы войну… И не было бы ни большевистского переворота, ни гражданской войны, ни всех последующих морей крови… Введением смертной казни и «малым количеством смертей» предотвратили бы куда большее зло…

Возможно, и так, хотя сегодня трудно сказать, послушались бы солдаты Корнилова, сумел бы он справиться с большевиками, получилось бы у него остановить уже вышедшую из-под контроля стихию… Но даже если бы сумел, то кровавый маховик совершил бы еще один круг, снова начали бы казнить, казнить, казнить. И никуда не делись бы те миллионы людей, которые вернулись в страну из окопов и принесли с собой военный синдром со всеми вытекающими отсюда последствиями. Большевиков-то, может быть, и остановили бы, а не вышла бы из окопов мировой войны новая власть, напоминающая правительство Муссолини? Не случайно, может быть, именно итальянский опыт позже, в эмиграции, вызывал интерес у многих «корниловцев»?

Но всего этого не произошло. История России — и история смертной казни — пошла по другому пути. 28 сентября 1917 года Керенский, жаждавший отмежеваться от всего, что делал летом того года Корнилов, приостановил применение смертной казни «до особого распоряжения». 28 октября 1917 года большевики, жаждавшие отмежеваться от всего, что до них делало Временное правительство, издали декрет о том, что «восстановленная Керенским смертная казнь на фронте отменяется». Однако уже 20 ноября снятый большевиками главнокомандующий генерал Духонин, отказавшийся начать переговоры с немцами о перемирии, был растерзан солдатами. Конечно, не было ни суда, ни приговора, но таким было общество, где якобы не действовала смертная казнь. А уже 7 декабря была создана Чрезвычайная комиссия, которая будет пытать и расстреливать, не обращая внимания на то, действует ли в стране институт смертной казни — или же на нее в очередной раз введен мораторий.

Наконец, 21 февраля 1918 года казнь опять была узаконена. Советская власть издала декрет «Социалистическое отечество в опасности», где, в частности, содержалось требование создавать батальоны для рытья окопов и тут же оговаривалось: «В эти батальоны должны быть включены все работоспособные члены буржуазного класса, мужчины и женщины, под надзором красногвардейцев; сопротивляющихся — расстреливать». Расстреливать на месте преступления, то есть без суда, предлагалось «неприятельских агентов, спекулянтов, громил, хулиганов, контрреволюционных агитаторов, германских шпионов».

Как мало времени понадобилось на то, чтобы от ограничения смертной казни «исключительными», в основном политическими, преступлениями прийти к необходимости расстреливать мужчин и женщин, не желающих рыть окопы, спекулянтов (торговцев на черном рынке в голодной стране), хулиганов (а как вообще определить уровень хулиганства, за который надо убивать?).

Ясно, что столь скорый разрыв с полуторавековой традицией смягчения наказаний и ограничения смертной казни стал возможен на фоне политических страстей, терзавших Россию в предыдущие десятилетия, психологической военной травмы и вакуума власти, которым воспользовались большевики. А еще, наверное, сыграло свою роль то, что смертная казнь все-таки существовала. Да, ограниченная, да, со все сужавшимся кругом применения — но она была, она никуда не делась — и как только ситуация в стране пошла вразнос, власть — будь то Корнилов в борьбе с большевиками или большевики в борьбе с немцами и своими политическими противниками — начала хвататься за это средство.

А дальше началась еще одна война — гражданская, которая только закрепила уже и так существовавшее пренебрежение человеческой жизнью. 5 сентября 1918 года, после покушения Фанни Каплан на Ленина, Совнарком принял декрет «О красном терроре», стоивший жизни тысячам людей.

Тамара Эйдельман. «Право на жизнь. История смертной казни». Альпина нон-фикшн, 2022 год.