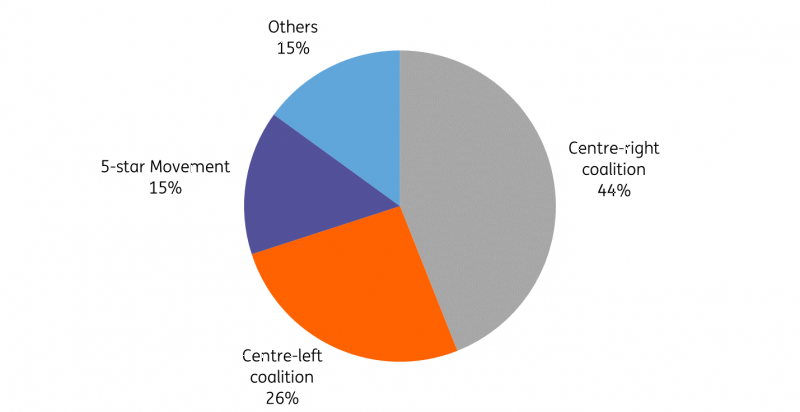

Although the victory of the centre-right coalition in the elections in Italy was expected, the success of Georgia Meloni, who leads the ultra-conservative Brothers of Italy party, is highly unusual. First, Meloni will be the first woman in history to head the Italian government. Second, for many years she has acted as an openly niche politician: her Brothers of Italy garnered the votes of a few far right, sometimes barely passing the three percent threshold required to enter parliament. Now Meloni and the "Brothers of Italy" received 26%, and her eminent allies Silvio Berlusconi and Matteo Salvini (8% each) took the places of junior partners in the coalition. Thirdly, for this reason, Meloni can hardly be called a populist – she is more of a traditional type of politician who does not strive at all costs to please the voter, but stubbornly defends her (in this case, rather retrograde) values. In this sense, her alliance with Salvini and Berlusconi may not be so strong.

In the European Union, nothing good is expected from the new Prime Minister of Italy: some media write almost about the revival of fascism. This is obviously an exaggeration: although Meloni gathers under her banner a certain number of freaks who yearn for the “great Italy” of the Mussolini era, her main political message is still different – upholding national, religious and family identity, which, in the opinion of the new Italian leader, threatened by a cosmopolitan and pan-European order. Nevertheless, Meloni clearly articulates his belonging to the collective West and, in particular, opposes Putin's aggression in Ukraine without any equivocation, unlike his coalition partners Salvini and Berlusconi, who are known for their ties to Putin. Responding to a congratulatory tweet from Volodymyr Zelensky, Meloni wrote: "You know you can count on our dedicated support in the fight for Ukraine's freedom." In addition, speaking in parliament on September 28, the new leader said that she would “not cede” key ministries to Salvini because of his “Russophilism”. These intentions, however, should not be overestimated, since the new prime minister's undoubted priority will always be domestic politics, which may well require compromises on the "Russian question" from her.

Of course, in the European system of coordinates, Italy still remains a country of predominantly leftist values, so Meloni's victory is perceived by most intellectuals and the Italian political class as another crazy step into the abyss – the previous ones were the rise in popularity of the xenophobe Salvini and the triumph of the declaratively unprincipled Five Stars. But there are also calmer assessments: for example, political communications specialist Alessio Postiglione, in an interview with The Insider, emphasizes that all these phenomena are not some sad feature of Italian politics, but part of the global trend (Brexit-Trump-Le Pen etc.), and, secondly, the reaction to the unfavorable for Italy distribution of the balance of influence within the EU. According to Postiglione, it is worth paying special attention to the fact that the general populist trend does not have really significant manifestations in Germany – this is due to the fact that it is the main beneficiary of European integration and therefore populists do not have mass support there. According to Postiglione, Meloni will have to get concessions from the EU in favor of Italy, and she has more chances than the too odious Salvini – in this sense, Berlusconi, who is a member of the largest and most respectable faction of the European Parliament EPP, is a much more useful partner. Fears that Meloni will become the “new Orban”, eroding European unity on the issue of attitudes towards Putin, should be taken more as an attack on her by the Italian left center that has gone into opposition.

Aldo Torchiaro, an analyst close to the left and therefore more critical of Meloni, admits, however, that "there are not many fears for the democratic order", and, moreover, he is very glad that Italy will finally have a woman prime minister. (Perhaps the fact is that he studied with Meloni at the same prestigious metropolitan school – and, taking their first steps in youth political activism, Torchiaro and Meloni were not always on opposite sides of the barricades.)

Generally speaking, the main problem of the Italian left is that it has become too long and firmly established as the mainstay of the establishment – and therefore the main target of the typically populist rejection of glossy politicians in TV ties. Characteristically, the current head of the Democratic Party (the flagship of the center-left coalition), Enrico Letta, is the nephew of Gianni Letta, one of Berlusconi's closest advisers. In the eyes of the mass voter, the differences within the political class, even between antagonists, do not always matter – especially since many times in the history of Italy it happened that antagonists found a common language and formed coalition governments. This explains the recent scandalous rise in the popularity of the Five Stars, which began their path to success with a declarative rejection of coalitions and the organization of political performance marches “Vaffa day” (the day “Go fuck yourself”). However, having reached the upper floors of power, the "Stars" failed to show off managerial successes, moreover, a split occurred recently in their ranks – the recent leader di Maio decided to take up his own political project. Nevertheless, in the September 25 elections, the Five Stars managed to gain 15.4% and thus retain a significant faction in parliament. Also related to the rejection of coalition politicking, as Postiglione points out, is the flow of right-wing protest votes from Salvini to Meloni – many voters have not forgiven the "captain" of the Northern League for the recent alliance with the left.

As one of the leaders of the Democratic Party, Matteo Orfini, writes now in his blog, the main unpleasant surprise of this campaign for him was that, having traveled, as usual, thousands of kilometers in his constituency, he met many loyal supporters, but none of them were happy to vote for the Democrats. The left is supported, roughly speaking, grimacing, out of inertia, following family or regional political traditions, because of the rejection of the right – but without sincere sympathy and faith. Symptomatic is also the steady drop in the turnout in the elections – to a record 63.91% (previously it had never dropped below 72%), and, according to polls, it was the Democratic Party that suffered the greatest losses. Orfini comes to the conclusion that the Democrats need to work on their new conceptual proposal to voters, re-reflect and formulate their political identity – which sounds sensible, but left-wing politicians have expressed such intentions not for the first time, but things are still there.

Perhaps, in the Italian example, we are now witnessing a curious transformation of the trend in modern political marketing. If 15-20 years ago it was most important to study the voter's moods with maximum accuracy and develop your product in accordance with them, now, paradoxically, it turns out that the consumer wants most of all to be convincingly explained what he should want. This phenomenon potentially opens the way to success for those who were previously unwilling or unable to adapt to mass demand, remaining within the narrow electoral framework of their political credo. This interpretation of Meloni's victory looks at least coherent – although it leaves questions about the longevity of her success.

Anyway, the main Italian political tradition is that none of the post-war governments lasted long. Representatives of small and medium-sized businesses – the backbone of the national economy – are accustomed to doing business without looking back at the leapfrog in official Rome and treating it like changeable weather. This perception, perhaps, still dominates in Italian society, so the expectations of significant upheavals from the coming to power of the centre-right coalition led by Meloni are greatly exaggerated.