The beginning of the war and Germanophobia

On June 28, 1914, the Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip in the capital of Bosnia, Sarajevo, killed the heir to the Austrian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife Sophia. In Vienna, the murder was known about noon, but no one worried. Newspapers were not printed on the day off, the emperor rested in the summer residence of Bad Ischl. After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, Europe experienced a "beautiful era" – a period of prolonged peace, technological progress and the flowering of culture. But the German Empire needed a war. The German government hastily assured Vienna of its unconditional support. In the margins of the telegram, Kaiser Wilhelm II scrawled : "Now or never: the Serbs must be finished." On July 28, 1914, under pressure from Germany, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia by direct telegram and began shelling Belgrade. Over the next few days, half of the European states were drawn into a large-scale confrontation, which would later be called the Great War, and a little later – the First World War. In total – directly or indirectly – 38 states participated in it.

Despite the fact that St. Petersburg, Paris and London were quite ready to enter the war from the very beginning, the decision to start it was made mainly in Vienna and Berlin. Historians reasonably noted that "if in the long run the responsibility for unleashing the First World War falls on all its main participants, albeit in different shares, then it was in August 1914 that German and Austro-Hungarian imperialism was most to blame for its provocation." The cause of the war was for a long time considered exclusively irrepressible military, political and economic ambitions of Germany. The Treaty of Versailles, which ended the First World War, contained clause 231: "Germany recognizes that Germany and her allies are responsible for causing all losses and all damages suffered by the Allied and Associated Governments and their citizens in consequence of the war that was forced upon them by the attack of Germany and her allies." The Entente countries charged the former German Kaiser Wilhelm II, among other things, with "the highest insult to international morality and the sacred power of treaties."

The cause of the war for a long time was considered exclusively irrepressible military, political and economic ambitions of Germany.

Germany waged an aggressive, sometimes barbaric war – used asphyxiating gases (Battle of Ypres), poisoned wells, destroyed rescue ships and hospitals, massacred occupied territories, destroyed religious and historical monuments (shelling of Reims Cathedral), attacked civilian ships (sinking " Lusitania). Millions of Germans lived outside the German Empire. Their situation with the beginning of the war turned out to be quite difficult. Obeying natural instincts, the inhabitants of the countries-enemies of Germany transferred hatred from the aggressor state to representatives of the entire nation. Germanophobia took over the world faster than Kaiser Wilhelm II of his enemies.

The irrepressible ambitions of Kaiser Germany

Germany, on the eve of the war, a militaristic, authoritarian state, wanted above all to challenge the political hegemony of Great Britain. Imperialist foreign policy course of the German government

Weltpolitik: assertive and aggressive, his goal was to return Germany to "a place in the sun" and turn it into a global power. Kaiser Wilhelm II, who most of all desired his own greatness, interfered in all foreign policy events, easily succumbed to manipulation if he was flattered or lied to, and in some way was personally responsible for provoking the war, although the entire noble elite shared his efforts.

Kaiser Wilhelm II interfered in all foreign policy events and easily succumbed to manipulation

Germany sought to achieve a revision of spheres of influence. Its colonial claims were growing . At the end of the 19th century, the German Empire took "under protection" the Marshall Islands, part of the Samoan Islands and other lands in Africa, Oceania and China, receiving territories of 2913.5 thousand km2 with a population of 15.652 million people. However, the German colonies were still substantially smaller than the British. The new empire could not resist Great Britain without a strong fleet, so it set a course for building a fleet of a fundamentally new level. It was obvious to everyone in Europe that Imperial Germany posed a significant threat and was ready to act aggressively. In 1899, following a visit by Emperor Wilhelm II to the Ottoman Empire, the Turkish government agreed to grant Germany a concession to build and operate the Baghdad Railway. At the disposal of the Germans passed a network of 2400 km, with access to Aleppo, Khanekin and the Persian Gulf. Thus, the Ottoman Empire was actually included in the sphere of German interests. Naturally, neither Britain nor Russia, whose influence in the region was infringed, liked this. The war was coming.

Within Germany, imperialist and nationalist sentiments were maturing, actively supported by the government. The desire for the “greatness of the Fatherland” is noticeable, for example, in the figures of the composition of nationalist organizations: the Kyffhäuserbund united 2.8 million people, the German Naval Union – 1.1 million. The Pan-German Union included many journalists, teachers and officials: all of them actively promoted the ideas that the Germans are an oppressed people "without living space", surrounded on all sides by enemies. The nationalists demanded from the emperor even more active protection of the interests of Germany – more rapid external expansion, the annexation of the Baltic states, Belgium, Luxembourg, the establishment of German political and economic dominion in the Balkans and the East. In 1897, B. Byulov was appointed Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. Already in his first speech in the Reichstag, he, without choosing accurate words, outlined a long-awaited course: “Those times have passed when the German ceded the land to one of his neighbors, the sea to another, and left himself the sky, where the purest theory dominates. We do not want to push anyone into the shade, but we also demand a place for ourselves in the sun. In 1902, the German General Staff published the collection Kriegsbrauch im Landkriege (Military Custom in a Land War), in which the Kaiser's military lawyers justified why a belligerent state was entitled to use all available means for military success, including those that contradicted established rules of international law.

“In the cellar at the table where Diederich sat, the idea of a powerful fleet grew stronger, it ignited with a bright flame, fed by good German wine, and glorified its creator. The fleet, these ships, these amazing machines are the fruit of bourgeois thought! Set in motion, they will make Germany a world power, just as the well-known machines in Hausenfeld make a well-known grade of paper called "World Power". The fleet was especially dear to Diderich's heart, and the idea of nationalism bribed Kohn and Geyfel first of all by the demand of the fleet. The landing in England was a dream, hovering in a misty haze under the Gothic vaults of the cellar. The eyes of the interlocutors flared up, everyone discussed the details of the shelling of London. The shelling of Paris was meant by itself and completed the plans of the Lord God for us. “For,” as Pastor Zillich used to say, “Christian guns serve a righteous cause.” (A fragment of the satirical anti-fascist novel by Heinrich Mann "The Loyal Subject". The work tells the story of an ardent admirer of the regime of Wilhelm II).

On August 4, 1914, Kaiser Wilhelm II delivered an opening speech at a meeting of the Reichstag, stating that "from now on he sees no parties, only Germans." His assertiveness forced even the forces that were initially opposed to it to agree to the start of the war. Thus, the leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, which had previously organized anti-war rallies, supported military loans. Mostly out of fear that the party would be banned altogether. An important role in legitimizing the war was played by the idea of a pre-emptive strike, necessary in advance to counter the aggressive ambitions of a hostile alliance from England, France and Russia. The Kaiser convinced everyone that Germany was waging a defensive war, defending itself against the aggression of the Entente.

An attempt to get rid of the Germans in the USA

During the decade before the war, the United States averaged a million immigrants a year. The country pursued an "open door" policy, not limiting the number of entrants. People moved to the USA most often for economic reasons – fleeing poverty, but sometimes – for political reasons. So, Louis Viereck, a member of the Socialist Party, after several conflicts with the state (first expulsion from Berlin, and then imprisonment), fled to America in 1896. Another socialist, Max Bedacht, also fled to the United States after taking part in a strike after which he was threatened with imprisonment. With the outbreak of the Great War, transatlantic travel almost ceased. Most of the liners were converted into hospitals or military cargo ships. The steamships that remained in commercial service were threatened by German submarine warfare.

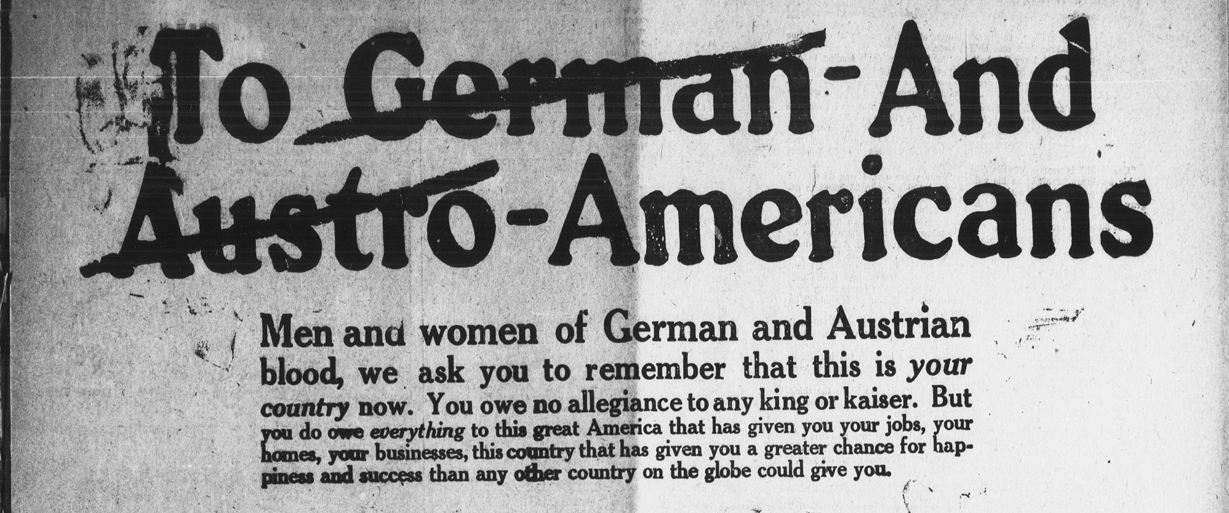

By 1910, Germans were considered the largest non-English speaking immigrant group in America. According to the 1910 census, one in eleven Americans was a first or second generation German. German remained the most studied foreign language. In some cities (Cleveland, Cincinnati, St. Louis and Chicago) there were German-language schools, German-language newspapers and even clubs. The German-speaking immigrant community was considered one of the most attached to their native culture. Some of them rushed to the German embassies at the start of the war, hoping to return to their country to join its struggle. Others, on the contrary, opposed the aggressive policy of Germany and decided to support the new homeland. In relation to the former, public opinion was much more merciless.

Even before World War I broke out, American opinion was generally more negative towards Germany than towards any other country in Europe. Over time, especially after reports of German atrocities in Belgium in 1914 and after the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, the Americans began to view Germany as the main aggressor in Europe. They were frightened not only by distant Germans supporting the Kaiser, but also by their own neighbors. The latter are often even stronger.

American opinion was more negative towards Germany than towards any other country in Europe

Throughout the US, individuals, groups, and politicians tried to rid themselves of German culture and German influence. Public and university libraries stopped subscribing to newspapers in German, and books written in German were stored in cellars. Some libraries even went so far as to destroy and burn them. Germantown (literally "German Town"), Nebraska, was renamed Garland in honor of an American soldier who died in the war. East Germantown, Indiana, was named Pershing; Berlin, Iowa became Lincoln. In June 1918, a congressman from Michigan introduced a bill that would require such changes in the naming of everything and everyone throughout the country: he proposed calling sauerkraut (Sauerkraut) liberty cabbage, hamburgers (hamburgers) – liberty steaks, dachshunds – liberty pups , and even rubella (German measles) – liberty measles. Some Americans urged not to perform the music of Beethoven, Bach and Mozart.

The Austrian conductor Ernst Kuhnwald, who led the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, was arrested on December 8, 1917 and deported to Königsberg – he was charged, in particular, with an interest in German music. It was said that after US President Woodrow Wilson turned to Congress for consent to declare war on Germany, Kuhnwald, conducting the American anthem, turned to the listeners, among whom were many Germans, with the phrase: "But my heart is on the other side." On March 25, 1918, the German conductor Karl Mack, who led the Boston Symphony Orchestra, was arrested. They said about him: "A good and patriotic German, he became very attached to this country and, on the whole, was a completely unhappy person." Mack not only included German music in all his programs, but allegedly (in fact, most likely he did not even know about this request) refused to perform "The Star-Spangled Banner", the US national anthem, which since the autumn of 1917 began to be played before concerts by many orchestras. Despite having a Swiss passport, Mack was sent to Copenhagen. US law allowed the arrest of anyone born in Germany, without respect for current citizenship.

US law allowed the arrest of anyone born in Germany, without respect for current citizenship

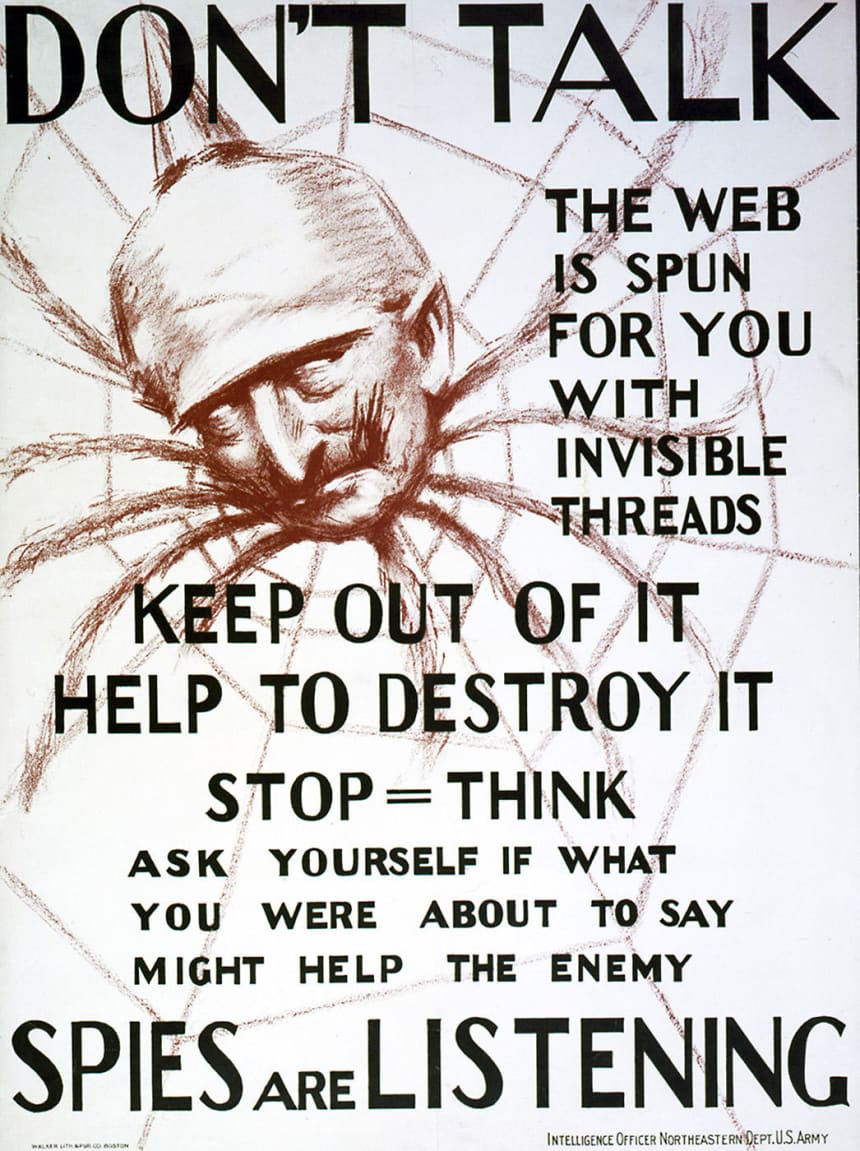

By the early 1920s, 34 states required schools to speak and write only in English. By 1918, South Dakota banned the use of German over the telephone and in public gatherings of three or more people. That same year, the Espionage Act was passed, prohibiting the mailing of any material "advocating or calling for treason, insurrection, or violent opposition to any law of the United States." The Sedition Act also prohibited speaking, printing, writing, or publishing any "disloyal, blasphemous, obscene, or offensive language" about the government, the constitution, the military, or the flag. At several universities, professors were accused of speaking unpatriotically under the Sedition Act, leading to the dismissal of some. American institutions (such as the Red Cross) forbade people with German surnames from joining them for fear of sabotage. The Ministry of Justice tried to compile a list of all German foreigners – they counted about 480,000. More than 4,000 of them went to prison in 1917-1918. The Germans and Austrians also needed permission to withdraw or transfer money from their accounts.

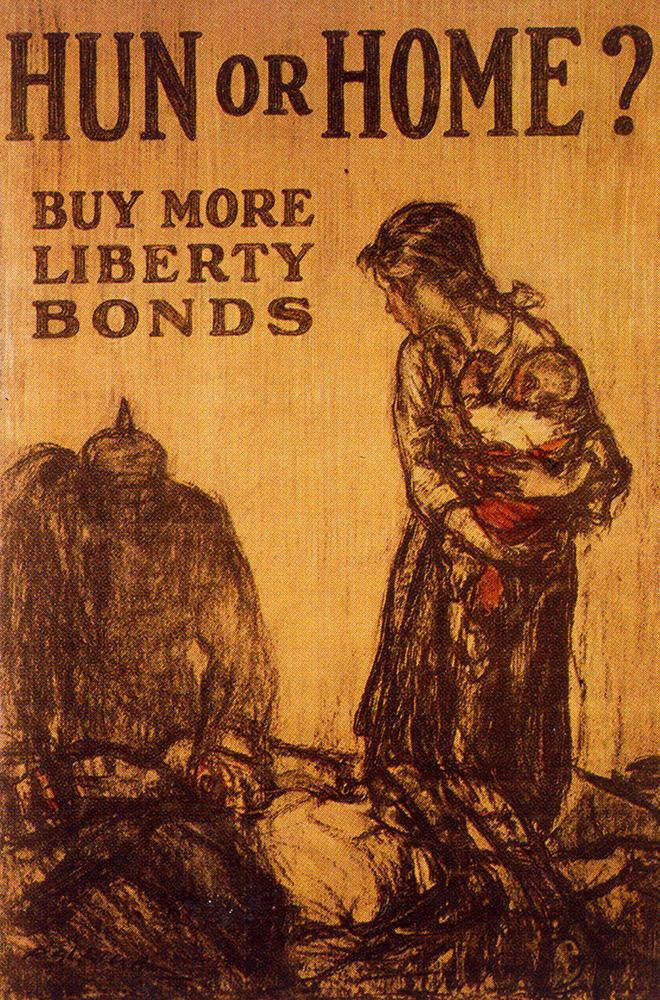

Newspapers wrote about the horrific crimes of the Germans, called them "Huns", reported on rapes and atrocities. The entire US press was openly Anglophile and anti-German. Propaganda-inflated Americans suspected spies everywhere. On December 29, 1917, the Collinsville Herald wrote: "Every German or Austrian in the United States, if not known for his absolute loyalty through years of cooperation, should be considered a potential spy." The most tragic incident of anti-German sentiment was the lynching of Robert Prager in Illinois in April 1918. Prager, a German native who applied for American citizenship, was suspected by neighbors of stealing dynamite. Although his guilt was not proven, the man was dragged out of the city, stripped, forced to wrap himself in an American flag and walk the streets like that, beaten, and then hanged. The court found the killers not guilty, but the lynching outraged many prominent Americans. Journalists Louis Star-Times recalled that other Americans are fighting for humanity abroad: "We cannot successfully fight the Huns if we ourselves are going to become Huns."

Many German Americans responded to these actions by declaring their position against Imperial Germany in public meetings to prove ties to America. Some bought war bonds as a show of loyalty. They changed the names, adapting them to the American tradition – for example, from Schmidt to Smith, from Muller to Miller. Even newspapers called for such action, asking bluntly: "Are you an American or a Hun?" Foreign-born soldiers made up 18% of the US Army. Almost one in five conscripts was born abroad. Many immigrants who entered the military did not speak English and did not know anything about the structure of the army and the state in the States. However, they were taught the language and assigned to separate divisions. So, for example, the 77th Infantry Division was almost entirely foreign. Italians, Chinese, Jews, Irish, Russians and others represented New York. The emblem of the 77th division depicted the Statue of Liberty – as a symbol of what choice the immigrants made when they moved to America, and what exactly they were going to protect.

Growing isolationist sentiment after the end of the First World War led to the closing of the "doors" to America. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 established the nation's first quantitative limits on the number of immigrants that could enter the United States. The Immigration Act of 1924, also known as the National Origins Act, made quotas even more stringent and permanent. В 1924 году весь иммиграционный процесс был изменен на визовую систему, которой мы пользуемся до сих пор.

Германофобия в Британии

В конце XXI и начале XX веков десятки тысяч немцев перебрались в Великобританию – в том числе из-за нетерпимости Германии ко многим вопросам. Британия, для сравнения, считалась куда более либеральной. По переписи 1911 года, в Великобритании проживали 53 324 иммигранта из Германии. Многие немцы в Британии занимались низкооплачиваемой работой, например, варкой сахара или работой в сфере услуг. 10% всех официантов Британии были немцами. Естественно, все эти люди не готовы были к возрастающему уровню враждебности.

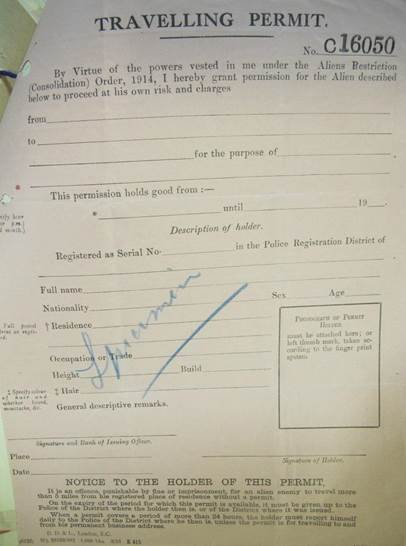

5 августа 1914 года, на следующий день после объявления войны Германии, Парламент принял Закон о регистрации иностранцев. Он требовал от них обязательной регистрации в полиции, чтобы при необходимости их можно было депортировать или интернировать (интернированием называют процесс принудительного задержания одной страной находящихся на ее территории граждан другой страны, если последняя находится с первой в состоянии войны). Передвижения и поездки вражеских иностранцев ограничили.

Закон ликвидировал немецкие газеты и клубы. Принадлежащие немцам предприятия оказались закрыты, а имущество и активы конфискованы без компенсации владельцам. Мужчин призывного возраста (17-55 лет), которых отнесли к категории вражеских иностранцев, арестовали и интернировали в специальные лагеря. Самый большой из них, Нокало, располагался на острове Мэн и на пике своего развития вмещал более 23 000 человек. Число интернированных росло в течение 1915 года: к июлю их было 26 173, а к ноябрю 1915 года – 32 440 человек.

Можно было подавать заявки об освобождении по национальному или личному признаку. В общей сложности подали больше 15 тысяч таких заявок, из них удовлетворили только 7343. Национальные основания включали профессиональные навыки или опыт, которые имели ценность для страны и военных действий. Личными основаниями могли быть возраст и немощь, продолжительность проживания в Великобритании, брак с женщиной британского происхождения или сыновья, служащие в британских вооруженных силах. На протяжении всей войны правительство депортировало немецких женщин, детей и стариков. К 1919 году в Великобритании осталось всего 22 254 немца.

Наиболее серьезным проявлением германофобии были антигерманские беспорядки, которые вспыхивали несколько раз – прежде всего после потопления немецкой подводной лодкой пассажирского лайнера «Лузитания» у берегов Ирландии 7 мая 1915 года (погибло 1198 человек). Беспорядки начались в родном порту «Лузитании», Ливерпуле, но быстро распространились по остальной территории страны. Практически в каждом немецком магазине выбили витрины. Особенно пострадал Лондон: атаке подверглись 1950 объектов недвижимости. В прессе немцев, как и в Америке, называли «гуннами», намекая на их жестокость. Стандартный заголовок того времени – «Никаких компромиссов с расой дикарей».

Британцы создавали образ Германии как «инициатора мировой бойни». Ее называли «агрессивной военизированной машиной», а кайзера Вильгельма II – «новым завоевателем». «Мясник» и «головорез», в изображениях британской прессы, управлял «солдатам-марионетками», проявляя «жестокий военный деспотизм». Эта пропагандистская линия давала Британии образ страны, несущей ценности западного мира, а Германии оставляла незавидную участь восточных варваров, умеющих и главное желающих только воевать. Немецкие солдаты описывались «агрессивными», «лютыми» и «настоящими зверьми». Повторялись сюжеты об изнасилованиях германцами женщин и нападениях на детей.

Германию называли «агрессивной военизированной машиной», а кайзера Вильгельма II – «новым завоевателем»

«Гуннской» речью кайзера, произнесенной в июле 1900 года, британская пропаганда активно иллюстрировала милитаризм и агрессивную внешнюю политику страны. Вильгельм II тогда сам сравнил Германскую империю с государством гуннов, сказав: «Великие заморские задачи, которые выпали на долю вновь созданного Германского рейха, эти задачи гораздо шире, чем могло ожидать большинство моих соотечественников. Германский рейх в силу своего характера несет обязанность поддерживать своих граждан, если они находятся под угрозой за границей. <…> Средство, которое позволяет ему сделать это, – наша армия».

Королевская семья сменилась название династии: с Саксен-Кобург-Готской на Виндзоров. Король Георг V отказался от всех немецких титулов. Принц Людовик фон Баттенберг был вынужден не только сменить фамилию на Маунтбеттен, но и уйти в отставку с поста Первого морского лорда, самого высокого поста в Королевском флоте. Немецких овчарок переименовали в «эльзасских» (Английский клуб собаководов повторно разрешил использовать наименование «немецкой овчарки» в качестве официального названия только в 1977 году). Нескольким улицам в Лондоне изменили название: Берлин-роуд в Кэтфорде переименовали в Канадскую авеню, а Бисмарк-роуд в Ислингтоне – в Уотерлоу-роуд.

Недовольство немцами в России

В Российской империи с началом Великой войны настроения в обществе были примерно британскими. Россия, оказавшаяся союзником Британии по Антанте, хотя и не считалась претендентом на статус «великой империи», тем не менее, явно его желала. Во-первых, и сама по себе, по своим прошлым историческим заслугам и своему месту в мире, во-вторых, и потому что только что пережила позорное поражение в Русско-японской войне, от которого, впрочем, неожиданно быстро оправилась.

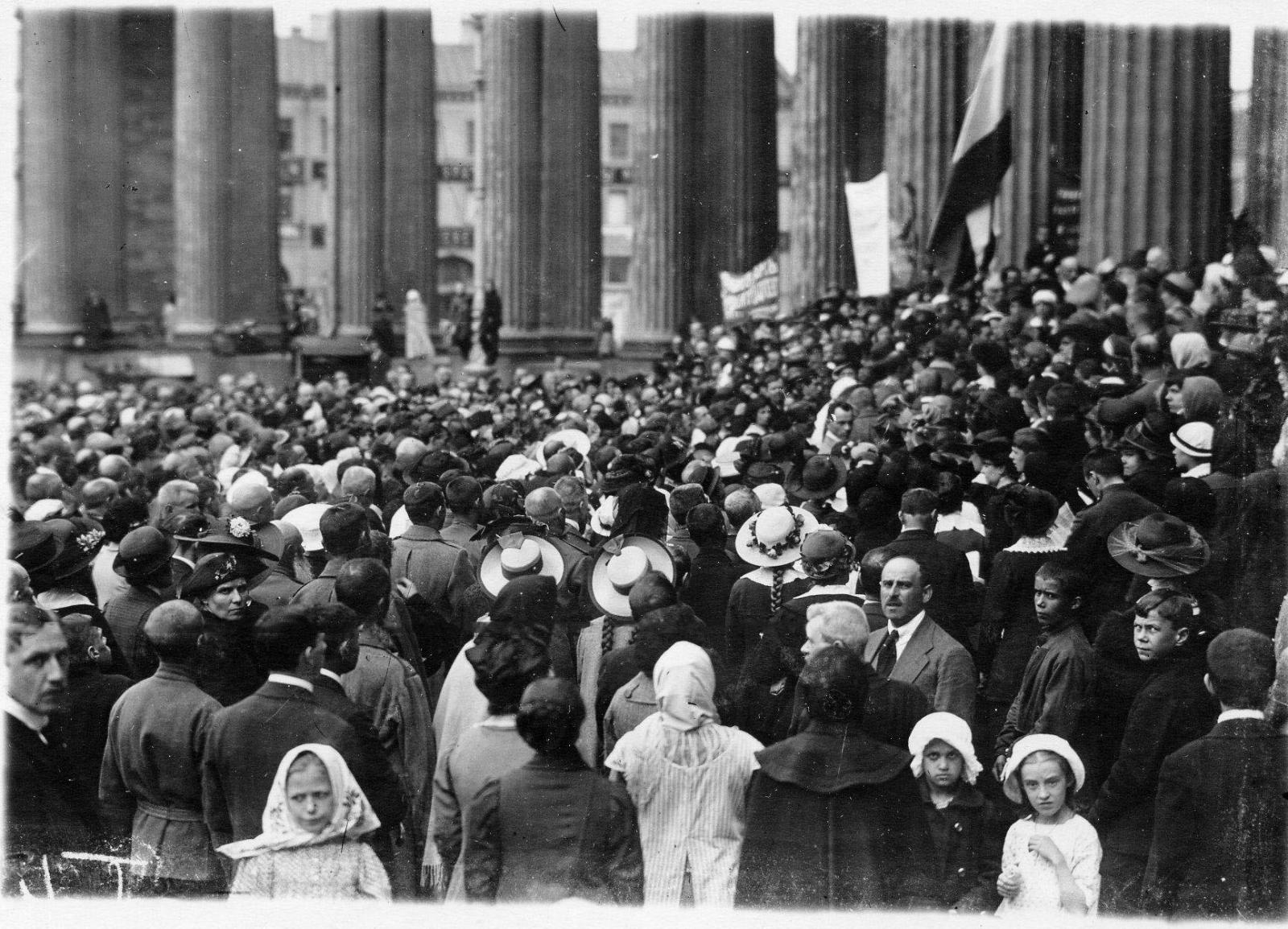

21 июля 1914 года толпа петербургских манифестантов обратилась к градоначальнику с просьбой удалить всех немок и немцев с телеграфных учреждений, потому что «немцы, враги нашего Отечества, все телеграммы передают своим братьям в Берлин». Лозунги толпы – «Бей немцев» и «Долой их». 22 июля город полнился слухами о некорректном отношении немцев к русским подданным, покидавшим Германию, и о разгроме в Берлине русского посольства. В течение следующих нескольких дней манифестанты громили немецкие магазины, производства, газеты и само посольство. После этого все уличные манифестации в Москве и других городах империи запретили. Тем не менее, германофобия нарастала и находила проявления. В Москве и Московской губернии в 1914 году произошло несколько антиавстрийских и антинемецких стачек – рабочие требовали убрать с заводов немецких коллег.

Чем дальше Германия применяла удушливые газы и другие незаконные способы ведения войны, тем сильнее росло недовольство. В апреле 1915 году в переименованном Петрограде произошел взрыв на Охтенском пороховом заводе. Его быстро приписали работе немецких шпионов – якобы они заложили бомбу. В город доходили слухи о недочетах снабжения армии. Голод и цены росли. Под германофобию попало само правительство: его начали активно обвинять в лояльности немцам и шпионаже в пользу врага. Диверсии Германии чудились утомленному народу то здесь, то там. Шпионами стали открыто называть членов царской семьи – Александру Федоровну и ее сестру Елизавету Федоровну. Призыв Великого князя Николая Николаевича «строго отличать заведомых предателей от верных слуг Царю и Родине, хотя бы и носящих иностранные фамилии» результата не дал. Антинемецкие настроения медленно превращались в революционные. 1 ноября 1916 года в Думе лидер кадетов Милюков завершил свое обвинение правительства и, в частности, императрицы Александры Федоровны словами: «Что это: глупость или измена?», и народ и армия однозначно ответили ему: «Измена», а в феврале 1917 года на плакатах написали: «Долой правительство! Долой немку!»

Конец войны или недолгое перемирие

Летом 1914 года в Германии быстро увеличивалось количество пропагандистских статей, создававших впечатление, что война победоносно закончится в относительно короткие сроки. Но уже с 1915 года значительная часть населения Берлина стала все острее ощущать на себе последствия морской блокады – англичане препятствовали ввозу в страну сырья и продовольствия. Германия не планировала затяжную войну, и в Берлине большую часть провизии израсходовали уже через несколько месяцев. С осени 1914 года власти пытались вмешиваться в производство и распределение продуктов питания. Плохая ситуация со снабжением и рост цен привели к фиксации максимальных цен на продукты питания, за которыми последовало всеобщее нормирование.

В феврале 1915 года Берлин стал первым городом в Германии, где выдавали карточки на хлеб. Рацион, установленный муниципальными властями столицы, первоначально составлял 2 килограмма хлеба в неделю или 225 граммов муки в день на душу населения, а вскоре норму муки сократили до 200 граммов. К концу 1915 года большинство продуктов питания в городе было строго нормировано. На практике их оказывалось почти невозможно достать даже по карточкам. Перед магазинами росли очереди. В Берлине и других городах Германии из-за продолжающегося продовольственного кризиса и несправедливой системы распределения продуктов питания происходили протесты и беспорядки. Из-за оптимистичных и бодрых репортажей прессы, общество, тем не менее, не было морально готово к проигрышу. К решающему моменту, когда Вильгельм II бежал из столицы, а в стране вспыхнули восстания, руководство империи осознавало свой провал уже несколько месяцев.

В июне 1919 года был заключен Версальский мирный договор. Проигравшая Германия лишилась всех колониальных владений. Эльзас и Лотарингия отошли Франции, часть территорий получила Бельгия. Страну полностью разоружили, разрешив иметь армию до 100 тыс. человек, офицерский корпус – до 4 тыс. На правом берегу Рейна установили пятидесятикилометровую демилитаризованную зону, на левом расположились английские и французские войска. Репарационные выплаты были огромными – около 20 млрд золотых рейхсмарок в первые 15 лет, около 132 млрд в следующие 30. Эти суммы делали невозможным восстановление в Германии экономики. Официально вину за Первую Мировую возложили только на Германию. Говорили, что французский маршал Фош, прочтя текст Версального договора, сказал : «Это не мир, это перемирие на 20 лет». Через 20 лет, в 1939 году, гитлеровская Германия напала на Польшу. Реваншизм, подкреплённый унизительными для немцев положениями Версальского договора, привел страну к новой агрессии.

Первая Мировая война, несмотря на ее «недостаточно тотальный» характер, стала первой войной, стершей границы между гражданским и военным населением. Странам-участницам войны пришлось мобилизовать все национальные ресурсы, включая общественное мнение. Исходящая от врага опасность представлялась как основная экзистенциальная угроза, поэтому враг должен был быть уничтожен, желательно навсегда. Радикализация настроений привела к германофобии. Несмотря на то, что Версальский договор содержал параграфы о привлечении к ответственности кайзера Вильгельма II, он сбежал в Нидерланды, где, в отличие от своего народа, никаких лишений не терпел.

Вильгельм II он сбежал в Нидерланды, где, в отличие от своего народа, никаких лишений не терпел

После окончания Первой мировой войны проблема беженцев приобрела беспрецедентный размах – по большей части из-за падения Российской империи. От 1 до 1,5 млн русских граждан бежали в Польшу, Чехословакию и Германию, Малую Азию, Маньчжурию и Шанхай. Чтобы справиться с этим кризисом, Лига Наций под руководством Фритьофа Нансена создала международные проездные документы специально для этих беженцев. Удостоверение личности выдавалось ежегодно. В нем указывалась личность, национальность и раса владельца, а также гарантировалось право на свободу передвижения. С «паспортом Нансена» владелец мог переезжать из одной страны в другую – искать работу или воссоединяться с семьей. Позднее нансеновские паспорта стали выдавать и армянам, пережившим преследования в Турции. Паспорт Нансена признали 54 странами для россиян; 38 стран признали его и для армян. Такой документ имелся у Игоря Стравинского, Владимира Набокова, Сергея Рахманинова, Зинаиды Серебряковой. За усилия по распространению паспорта Нансена Нансеновская международная организация по делам беженцев получила в 1938 году Нобелевскую премию мира. И хотя проблема беженцев оставалась далекой от разрешения, потому что их продолжали делить на «плохих» и «хороших», во многом миграционный кризис, наступивший после Первой Мировой, стал подготовкой к еще более масштабному и драматическому переселению народов. Оно готовилось прийти в Европу с новой войной.